The 2018 Oklahoma Irrigation Conference, March 8, in Weatherford, Oklahoma, brought farmers and researchers together to discuss how to make every drop of applied water count.

Jason Warren, associate professor in Plant and Soil Sciences, Oklahoma State University, shared research data comparing the water usage of corn to grain sorghum across environments of Oklahoma.

Corn, he explained, is a racehorse of a crop—when conditions are not exactly ideal its yields can be dramatically unstable. Sorghum, however, requires good management to be close to as productive as corn, he added.

“Still, it can handle much harsher conditions than corn and recover from water stress twice as fast as corn,” Warren said. “And, it’ll come out of that stress and start growing again.”

While farmers aren’t paid based on the inches of water they apply to a field, they do have to account for the cost of applying that irrigation to their fields. In a Texas County trial, Warren compared corn and sorghum yields on the amount of applied water. When looking at the net return per inch of irrigation, grain sorghum outperformed corn.

Grain sorghum can’t compete on farms with 230 or more bushels per acre average corn yield targets, Warren said. “But when corn yield is limited to 180 to 190 bushels per acre average, it pays to consider sorghum.” The trade off is the grain sorghum crop will require more intense management than a corn crop. Additionally, in the High Plains, it costs one-third the crop insurance premium to insure corn as it does to insure sorghum, he added.

For farmers looking to grow grain sorghum on their irrigated land, it pays to understand the soil type and water capacity of the field as well as the evapotranspiration rates of the crop.

The key to irrigating any crop is to provide enough water at the right time to replace the moisture lost to ET. Sorghum is more resilient than corn, Warren explained, because its peak ET is seldom ever above the replacement capacity of 6 gallons per minute per acre, and it could get by with just 4 gallons per minute per acre capacity.

“We typically have plenty of water to manage, we just need to remember to not overwater,” Warren said. “We need to make sure we have enough water to keep it at field capacity until it develops heads. And then stress it at a 75 percent ET replacement rate to get it to mid-bloom. Then we can give it a heavy dose of water and get it to full cover when we can turn off the irrigation and get a yield of 17 to 19 bushels per inch of water.”

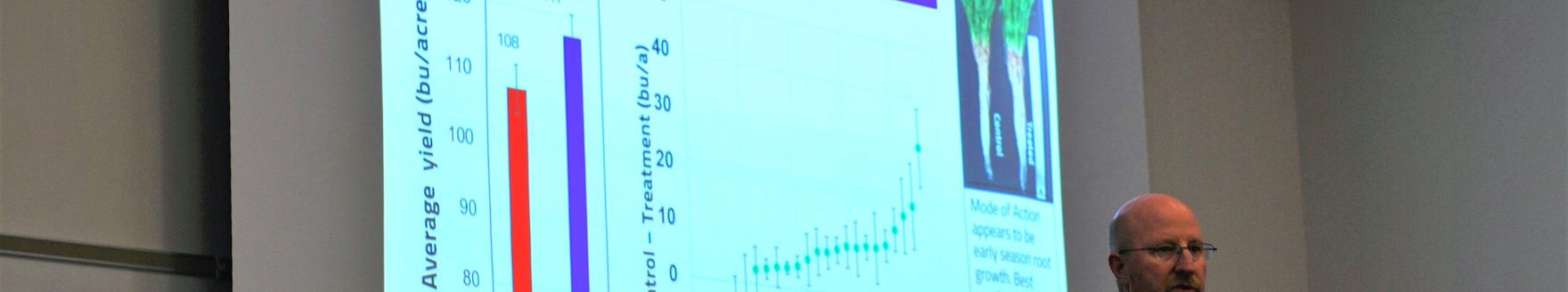

For corn, though, the key is to stress the crop in a cyclical manner early with a multi-day drydown period between applications. That causes the roots to dig deeper into the soil.

“Slow down the pivot to three to six days per revolution and get those roots down deep,” Warren said. “The early season period stress will get those roots to grow.”

When you look at the averages, farmers might be decreasing their water use by 10 percent, but they could be increasing their yield 10 percent on average because they are extending the life of the Ogallala Aquifer and making more bushels from improved crop health.

Energy and water

Scott Frazier, associate professor in Biosystems and Ag Engineering, OSU, spoke about the importance of irrigation energy and water use audits on established systems.

“Energy is one of the biggest single expenses per irrigated crop field,” Frazier reminded growers. Frazier and his team conduct audits on irrigation systems. In several instances they have found farmers could save thousands of dollars per year just by ensuring their systems are running at peak potential.

Even better, they could save water for future generations.

“Ground water recharge rates vary but are so slow it’s almost a fixed amount asset. So you have to manage the resource, especially in the western part of the state. You have to ask yourself if you want to have a ‘crash’ or a ‘soft’ landing for the future generation who will be on the land.”

Is your well efficient?

There are four key things to check on an irrigation well to see if it is at peak efficiency:

- Engine or electric motor;

- Pump;

- Water distribution; and

- Operations management.

In many cases older, worn out internal combustion engines, electric motors and pumps could be costing the farmer more in pumping efficiency than they are saving in replacement costs.

In several instances, Frazier said, he and his team are starting to see older casings fail at 250 feet or deeper. This can bring in sand and mud that can compromise pumps and eat through turbine blades and bearings.

“We’ve seen incorrect pump components that were never optimized or sized correctly,” Frazier added. “We know the aquifer is lowering and getting off of the efficiency curve. Variable speed drives, in the future, could knock us back onto the efficiency curve.”

Most importantly, though, is managing operations as effectively as possible, Frazier said.

“You can have the most energy efficient irrigation equipment, but that can’t help if the water is misapplied,” he said. Ultimately, farmers are at the switch and it’s their management decisions that can save them money and water in the long run.

Jennifer M. Latzke can be reached at 620-227-1807 or [email protected].