Amid the semiarid grain fields of Kansas, Thomas County farmer Steve Ziegelmeier was searching for an alternative.

It was 2008, and Ziegelmeier wanted a bridge crop to plant between dryland corn and wheat, skipping summer fallow. He also wanted to keep a cover on the ground.

It might seem like an impossible idea in northwest Kansas where average rainfall is about 20 inches a year. Ziegelmeier, however, following the recommendation of another regional farmer, quietly planted a small acreage to field peas and hoped for the best.

A decade later, Ziegelmeier is part of a slow but steady transformation across the plains. As consumer demand for health foods expand, field peas—which are high in protein—are spiraling from being unknown to taking root in Nebraska and Kansas.

“I’ve always liked to experiment,” said Ziegelmeier, adding, with peas, “I think the potential is there.”

Skipping fallow

Summer fallow is a common part of the High Plains rotation. In areas of limited rainfall, it helps recharge soil moisture before planting wheat in the fall. However, as farmers search for ways to maximize profit, there is growing interest from farmers like Ziegelmeier to replace fallow with pulse crops like field peas, said Lucas Haag, the Kansas State Research and Extension northwest area agronomist.

The idea, Haag noted, is that “growers can profit better off of planting something on those acres rather than just leaving them idle. What we were really looking for was an alternative to fallow—something that could be a reasonable cash-crop alternative.”

Pulses are legumes that are harvested solely for the dry seed. Spring field peas are a cool-season crop that fix nitrogen in the soil.

Acres have grown from a few thousand a decade ago to nearly 55,000 in Nebraska last year. In Kansas, acreage has expanded each year since K-State began rotation studies on the crop in 2009.

Based on the calls he received this winter, Haag estimates Kansas farmers could harvest more than 15,000 acres of field peas this summer.

Not suitable for the Southern Plains

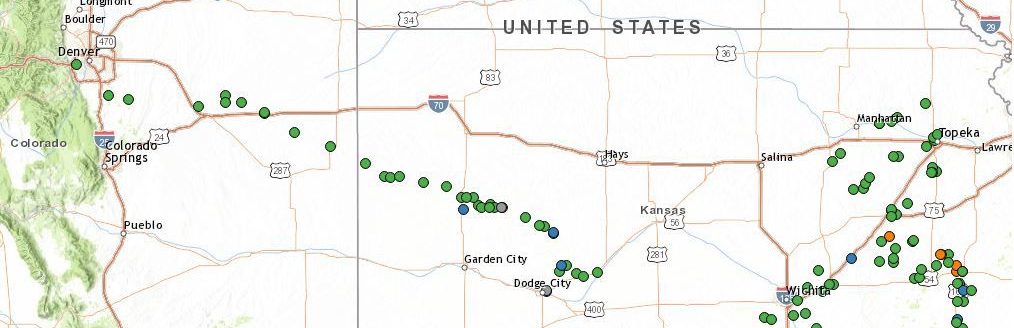

From 2009 to 2012, Haag studied field pea rotations at university sites at Colby, Tribune and Garden City, Kansas, along with one location in Texas.

Southern plots didn’t do well, Haag said.

“I don’t feel comfortable with peas south of the Smoky (Hill River) and certainly not comfortable south of (Kansas) Highway 96,” Haag said. “Anytime we went down there, we have had our lunch handed back to us with the heat burning us up during flowering and pod fill.”

Results, however, are promising in northern areas, Haag said. Meanwhile, farmers east of U.S. Highway 183 in northern Kansas and Nebraska are experimenting with field peas before wheat instead of soybeans.

K-State doesn’t have field studies in this area yet, but Haag said producers who planted peas are seeing higher wheat yields. One reason is, unlike soybeans, peas quit using water at the end of June, so farmers have more time to build moisture back up in those fields.

Peas before wheat also allow farmers to get their wheat planted on time, he added.

“I’m getting more questions from north-central and northeast Kansas guys wanting to add another crop,” Haag said. “Wheat after soybeans can be a real challenge, but peas after beans would be better.”

Emily Paul, sales director with North Dakota-based seed company Pulse USA, said field peas are beginning to take off on the East Coast. The company has farmers in Pennsylvania and South Carolina testing field peas in their rotation.

While some farmers are planting field peas as a cropping alternative, others are utilizing field peas in their cover crop mix, she said.

Still a few hurdles

There are hurdles to overcome planting field peas on the High Plains, Haag said. Most varieties are developed in Canada, Europe and the Pacific Northwest and not bred for the Midwest climate. Having more varieties suitable for the region would help with issues like yield stability and heat tolerance.

K-State is working with a U.S. Department of Agriculture pea breeder in Washington state to find better varieties, Haag said.

The university began conducting variety tests in 2014.

The learning curve is another challenge farmers face, Haag said.

Producers should be aware of their herbicide history. Some products used on corn and sorghum can carry over and damage the pea crop.

Peas use 3.5 inches more water than fallow. Wheat yields also average about 4 to 8 bushels less an acre in northwest Kansas after peas compared to no-till fallow, Haag said. The yield reduction compared to tilled fallow would be less.

However, K-State field studies show, regarding profit, farmers are still better off planting peas in most instances.

The long-term average pea yield at Colby is 24.5 bushels an acre, which is profitable, Haag said. Depending on the weather, some plots have yielded as low as 8 and as high as 40 bushels an acre.

“It’s not a get-rich-quick scheme,” he said, adding producers need to know their cost structure.

Growing markets

Ziegelmeier is finding peas can be a profitable niche. He said he has even trucked the commodity to the Dakotas a few times to capture higher markets.

With acres increasing, the pea market is expanding closer to home. The Gavilon Group’s Hastings, Nebraska facility has sourced field peas from farmers since 2016, said Mason Nicklaus, a merchandiser with Gavilon whose focus is specialty crops.

“If you look at what peas have done in the last five years, they have grown extremely,” said Nicklaus, who estimated a 50 percent increase in production in that time. “Having a market has helped farmers’ confidence to put acres down.”

Meanwhile, the growing health food and pet food markets have been a windfall. Field peas fit a market segment American consumers are requesting, Nicklaus said. He added more pet owners want pet food without grains. Peas also get used for non-dairy products.

A few big-box retailers are selling pea milk, an alternative to soy and almond milk, especially for those with nut allergies. Some also use peas as a supplement for wheat flour to make bread.

“That is just the tip of the iceberg,” Nicklaus said. “The products on the shelf made with pulse crops have gone through the roof.

“Field peas are 100 percent non-GMO. They are gluten-free, high protein. They check off all the marks the American consumer is after.”

That’s just one growing segment, Nicklaus said. One of the biggest markets for peas is the government’s food aid program. At Hastings, field peas are split and the hull, which is mostly fiber, is removed. Countries like Yemen and Ethiopia use them to make split pea soup.

According to a study by a Montana State University agricultural economist, between 2002 and 2012, food aid totaled 17 percent of all dry peas produced and 24 percent of all exports. A majority of Gavilon’s peas are part of that market.

Field peas can also be eaten raw, Nicklaus said.

“I’ve even have had inquiries from prisons systems,” he said. “It is a cheap food source. It is 25 percent protein. You can eat a handful of field peas and you are full.”

More work on pulses

Haag’s work will continue in northwest Kansas. He is garnishing more support as pulse companies offer more varieties for the university to test.

Haag is exploring a project that would phenotype around 400 different genetic lines of peas in an effort to find and develop genetics best suited for the environment.

Other pulses being researched include winter peas, which were first planted at Colby in fall 2017. Next year, the university will begin work with chickpeas.

As varieties improve, Ziegelmeier sees more acres being sown to peas.

“We just need programs down here,” he said. “I think we will get the right ones eventually. If we can get the genetics down here that will work for us, I think we will be alright.”

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].