No base acre loss seen in Senate farm bill

Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue, Kansas Republican Sens. Pat Roberts and Jerry Moran, as well as Rep. Roger Marshall, R-KS, attended a recent meeting with farmers at a farm near Manhattan, Kansas. In response to a question, Roberts stated that no farmer would lose base acres.

Most experts believe the loss of base would significantly lower land values on those acres that lose their base. It is typical at land auctions to note the number of base acres and program yields for the land to be sold.

Ag lenders will be very nervous about changes in base acres, too, because most farmers’ assets are tied up in land values. So even if farmers have no plan to sell their land, their net worth would shrink if they suffer a base reduction. That will affect a farmer’s borrowing capacity at a time when they need more financing.

As stated by Roberts, there is no reduction in base acres in the Senate bill. The bill does require the secretary to review the administration of base acre determinations and submit a report back to Congress within two years after passage of the farm bill. However, at this time, there would be no adjustment to base acres.

In 1996, Roberts was the leader for the Freedom to Farm concept. Prior to the 1996 law, farmers had to plant the program crop on a specific crop base to receive commodity payments. As a result, farmers were required to plant wheat on wheat base for the commodity payment, when at the time the market didn’t want any more wheat.

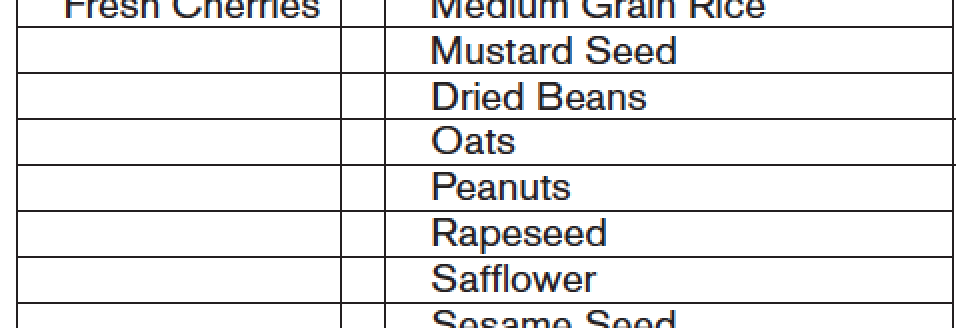

Freedom to Farm allowed farmers to plant crops other than wheat on wheat base and still receive the wheat payment. About the only exception to other crops were the planting of fruits and vegetables, but it did allow forages and oilseeds to be planted on those wheat (and other crop) base acres.

An example of crop acres being shifted to other crops after the introduction of Freedom to Farm is demonstrated in the largest wheat county in the USA. Historically, Sumner County, Kansas, has often been the largest wheat county in the USA, only swapping rankings with Hill County, Montana, in terms of acres planted.

In the early 1980s, Sumner County, Kansas, farmers planted over 500,000 acres of wheat. Today they plant less than 350,000 acres of wheat. As a direct result of Freedom to Farm, they have shifted those base acres to other crops, primarily soybeans, corn and grain sorghum.

Sumner County farmers did exactly what policy-makers were hoping for in 1996. Without the requirement to plant wheat in order to receive the wheat commodity payment, they did plant in response to the market. Minor crops such as cotton, canola and sunflowers have also been planted on Kansas wheat base. It is fair to say that Kansas farmers, especially in the west, have taken advantage of Freedom to Farm’s planting opportunities.

A few producers took full advantage of the Freedom to Farm’s market-focused policy by shifting their entire operation to producing alfalfa, triticale, rye, brome grass and other forages for hay and grazing on their base acres. The House bill requires a minimum of 0.1 of an acre to have been planted to a program crop during the years 2009-2017. Under the House bill, any producers who shifted all of their base acres to non-program crops, such as forages, will lose their base.

Sens. John Thune, R-SD, and Sherrod Brown, D-OH, submitted legislation to eliminate any base acres that were under-planted to program crops. This would have eliminated base acres for a “large” number of Kansas producers that have been producing alfalfa and other non-program crops on base acres.

This policy would have caused the largest loss of base acres among the three alternatives. The Thune-Brown proposal was primarily an effort to find funding for improvements to the Agriculture Risk Coverage program.

The under-planted base acres policy change is not expected to be offered as a floor amendment, so likely it is done for this farm bill. However, many analysts expect that the base acre issue will be raised in the next farm bill. Producers who shifted their operation to all forages and want to retain their base should consider planting a few acres to wheat or oats for haying and grazing.

This will meet the House requirements for retaining base in the next farm bill. This assumes the Senate language on base acres is adopted for this farm bill. If the House language is adopted, it is too late. These producers will have lost their base.

Planting a few acres of a program crop only helps with the next farm bill, but no guarantee that will retain a producer’s base then.

Freedom to Farm was probably the most market-focused policy change in the past 40 years. The closer is that base/payment acres are tied to actual planting, the greater the risk of a World Trade Organization violation. Tying base acres to current plantings is moving away from a “free” market, and returns us to the policy prior to 1996 that required farmers to plant program crops as a condition for receiving commodity payments.

Freedom to Farm has done what it was supposed to do: it has allowed farmers to plant for the market and not for the government payment. Over the past 20 years, Kansas has become a very diverse crop state. It is true some of that shift in crop plantings was the result of technology improvements, but none of this crop acreage shift would have happened in Kansas and other Great Plains states without Freedom to Farm.

The “bumper sticker” argument is we should stop paying commodity payments on land no longer being “farmed.” That depends on one’s definition of farming. Many of these forages require planting and fertilizer applications. These forages also require several trips across the field that include mowing, raking, baling and picking up the bales. For most reasonable people, that looks like farming, with tractors and agricultural equipment.

The second argument is that the 1996 Freedom to Farm legislation was supposed to be a transition to a “free” market by elimination of commodity payments after 2002. If that had happened, the timing would have been nearly perfect, as those continued payments would not have contributed to inflating land values and cash rents during the mid-2000 years. Had those values not been bid up, farmers’ current financial situation would have been similar with lower rents, but without government payments.

In theory this “free” market policy would have saved $1.7 billion in administrative cost to operate the Farm Service Agency. Anyone who believes in that fairy tale is out to lunch. FSA employees would have been moved to other government jobs, but many rural counties would no longer have a USDA office.

Too many non-farmers had a vested interest in the commodity programs to eliminate FSA and the commodity programs completely. So policy-makers will continue to make small policy changes around the edges by reducing the Adjusted Gross Income limits (the Senate cut the Adjusted Gross Income limit from $900,000 to $700,000), increasing the minimum ARC yield from 70 percent of the T-Yield to 75 percent, and payments based on the farm location versus the administrative county, which is current policy.

Conclusions

The Senate bill is very nearly the same program as the current program. Senators did provide some additional funding to expand trade and they made a few minor changes to crop insurance. Because commodity prices have been falling, that will lower the strike prices under the ARC formula.

No reason to get excited just yet, as farmers will not need to make a decision until next spring. The two versions of the farm bill will be sent to a conference committee, where the differences such as base acres will be reconciled. Then it will have to go back to the floor of both chambers for a final vote.

One would expect there will some amendments offered that will also need to be addressed. So the final law needs to happen really “fast,” to leave time for FSA to prepare for a fall wheat sign-up. It would be better for wheat farmers if sign-up did not happen until the spring. That will give wheat farmers more time evaluate their options based on more price and yield information.

If we are in the middle of a drought next spring, that might influence a farmer’s decision. Finally, any payments provided under the new program will not be paid until October 2020. There are two payment periods still left under the current law.