Webinar details drought, fire conditions in Colorado

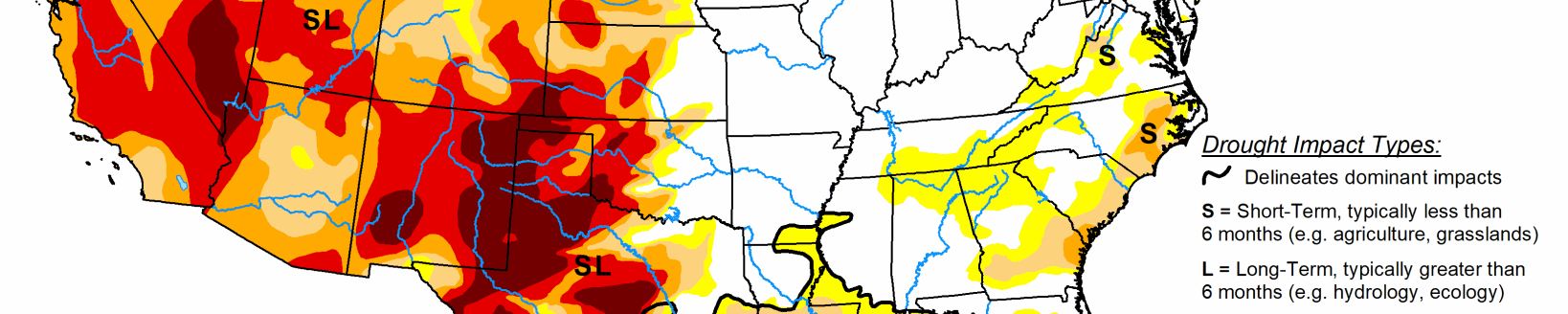

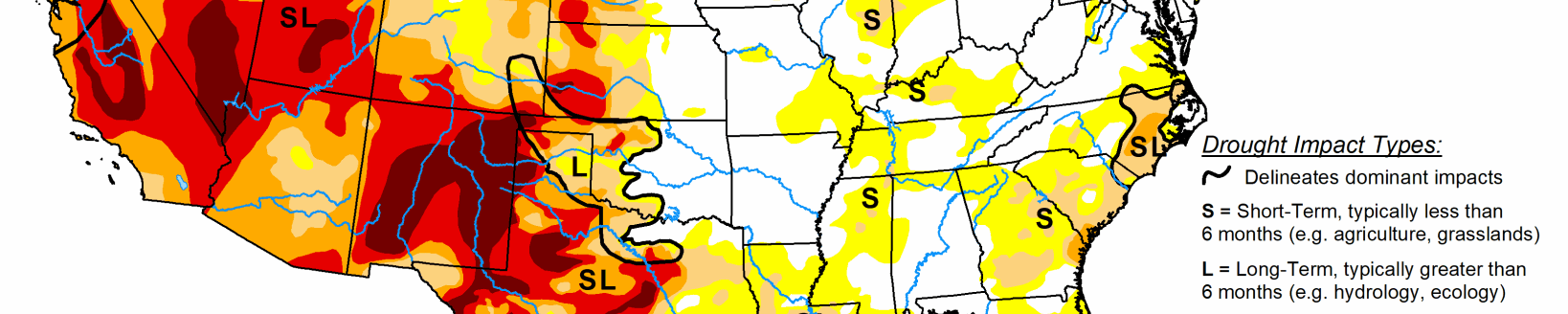

Colorado and many surrounding states are suffering from ongoing drought conditions. As of July 9, about 34% of Colorado is in the D3, or extreme drought, rating on the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Colorado Assistant State Climatologist Becky Bollinger spoke during a July 9 webinar hosted by the National Integrated Drought Information System, the Southwest Climate Hub, Colorado Climate Center at Colorado State University, and the Rocky Mountain Area Coordination Center.

Bollinger said in early July there was a D4 rating introduced in the far southeast corner of the state—Baca and Prowers counties—but it has since been removed after the area received about an inch of precipitation. The rating only lasted a week.

“But right now we’re still in a very concerning situation where 69% of our state is in some drought category and over half of the state is in a severe drought or worse category,” she said.

July started without any drought or abnormally dry conditions in the state.

“We had an excellent snowpack year last year, very late melt-off of snow and that really helped the region become completely drought free,” Bollinger said.

A lack of monsoon moisture in August 2019 led to increasing drought conditions as fall approached. Through winter, there were a few D2 ratings introduced.

Bollinger said the soil moisture levels at the start of the cold season are an indicator of how things are going to progress.

“It’s your first bucket of moisture,” she said. “So if you start the soils off dry at the beginning of the cold season, that’s a deficit you’re going to have to make up sometime later in the water year.”

A water year is from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30 of the following year. This is more of a natural indication of how the precipitation falls rather than the calendar year.

Reduced snowpack and soil moisture levels will ultimately impact the length of the summer fire season and the water supplies for Colorado.

“As we move longer term into drought, we start to worry more about the hydrology of the system and our water supplies,” Bollinger said. “Right now our water supply is still doing OK.”

Water supplies have already been greatly reduced for Colorado’s agriculture. Bollinger has heard from a number of Farm Service Agency and Colorado State University Extension that farmers are chiseling wheat to keep it from blowing; there have been many grass fires in southeast Colorado; and ranchers are purchasing hay and requesting emergency grazing, selling cattle and running out of irrigation water.

Where from here?

Bollinger said the importance of summer and fall precipitation for Colorado is often overlooked. June is when the most significant portion of the precipitation for parts of the state.

“June is definitely a part of the wet season,” she said. “We get a lot of regular and consistent thunderstorms.”

Bollinger said moving past the continental divide, things start to dry out, especially in the southwest corner and Four Corners region.

A lot of the wet season moisture tends to shift more south as the bulk of this moisture comes from the monsoon season. It comes up from New Mexico and Arizona, extending even further into the Arkansas Valley than just the southern part of the state.

Bollinger said the Climate Prediction Center’s temperature and precipitation outlooks for the months of July, August and September are leaning slightly toward a drier than average signal.

“But there’s not a lot of confidence to that,” Bollinger said. “So I would say over the next few months, that there is a lot of uncertainty with that precipitation forecast.”

For temperature forecast, there’s a lot more certainty in continuing to see warmer than average temperatures through the end of the summer.

What about the monsoon? Bollinger believes it’s coming. For this region, the monsoon starts in the southern part of the United States and in Mexico, then travels to southern New Mexico and Arizona. Dew points above 54 degrees have been defined as critical for the start of a monsoon season.

“From mid to late June, we are on that rise,” Bollinger said. “Which means we’re hoping that consistent monsoon moisture should be in the southern area of the United States very soon, and then we hope that it will begin its travels up to the north.”

Unfortunately, Colorado hasn’t had as much benefit from the monsoon in recent years.

Bollinger questions whether the deficits in the water year can be made up, and for a lot of areas in southern Colorado, the answer is “probably not.” For instance, Baca County in southeast Colorado, as of the July 8 observation, they are at an almost 7-inch deficit or 36% of average.

“There is no situation where we could take historical precipitation and get back to our long-term average,” Bollinger said. “If we get average precipitation for the rest of the water year, we would end at 60% of average.”

The southwest side of the state is facing a 6.5-inch deficit, or 50% of average. The area near Mesa Verde National park is likely going to end their water year between 10 and 12 inches of precipitation.

“And possibly worse if there’s no showing of the monsoon,” Bollinger said.

Monsoon season plays a pivotal role in whether or not there is a fire season in Colorado, Tim Mathewson said. Mathewson is a fire meteorologist with the Bureau of Land Management. Typically, wind events correlate with an uptick in fire occurrences and that starts in March and April.

“Spring precipitation is very important,” he said. “When these fields come out of dormancy and start to green up or take on moisture, if their soil moisture is low or there’s no moisture to take on they become drought stricken, and those live fuels can take on or not take on moisture but they’re going to support fire.”

When the vegetation and trees begin to take on moisture, they work to suppress fire. The green up allows them to not burn as readily. In drought years, that is not the case.

“It’s really dependent on the fuel moisture of those live fuels,” Mathewson said.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].