The blue sign along the dirt road declared Huscher’s death in 1984.

Why then? Linda Chubbuck doesn’t know. The longtime resident can’t think of a thing that happened on that date. She could argue that the Cloud County, Kansas, community has been on life support for decades. The post office closed in 1934. The school shuttered in the 1960s. Only a handful of homes remain.

Yet, it’s hard to declare a town deceased if there is still a faint heartbeat.

Each August, trucks filled with grain rumble across the scales and dust rises into the air at the 114-year-old elevator in town—a business Chubbuck’s family operated for more than 50 years. It’s now owned by Mike Pruitt, who toils through the autumn cleaning and treating farmers’ seed wheat from the town’s lone business.

For Chubbuck, who grew up helping her parents operate the old wooden elevator along the Santa Fe line, Huscher brings back happy memories.

“I grew up in wheat harvest,” she said. “Growing up here was fun and very colorful.”

The Huscher brothers

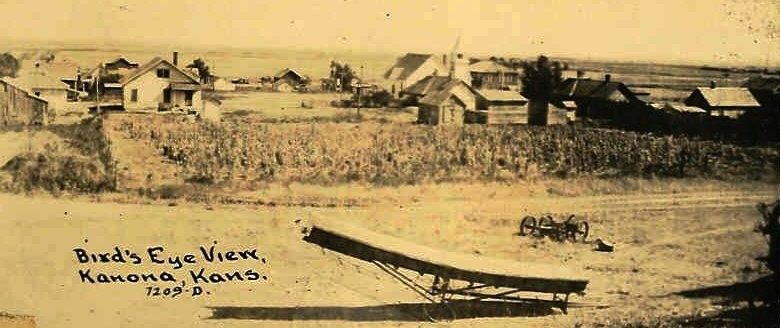

Settlement was just beginning to move westward when three brothers established Huscher, Kansas.

Gottlieb, Charles (Ernst), William and Frederick migrated with their parents from Germany to Canada in 1847. Around 1870, they followed the call for free land to Cloud County at a time when Concordia was just a cluster of shacks, said Ron Huscher, whose great-grandfather was Charles.

William, whose claim was jumped, eventually moved to Colorado while the other three built sod homes in the area southeast of Concordia. They began to farm.

Despite drought and a grasshopper invasion in 1874, the family stayed, raising their children and helping establish businesses in the tiny town.

Huscher, who lives near Kansas City, and has researched his family tree, said Charles and his wife had 12 children of their own. A few weeks after his grandfather, also named William, was born in 1880, the family moved to a stone house Charles built.

Huscher had a store and blacksmith and Charles’ son, David, operated the post office and purchased grain for a Kansas City company, according to the Concordia Blade-Empire. Kent Johnson, Chubbuck’s former husband, said there was a general store in Huscher as late as 1931. It appeared the store had many owners.

“I doubt that it was very profitable, especially after most people got cars and could go to Aurora or Concordia to do their shopping,” Johnson said. “I remember seeing a photo of the storefront once, and it was advertising shoes, I think.”

However, it was between 1902 and 1904 that Bossemeyer Brothers of Nebraska built the current elevator—an improvement over farmers scooping grain from their wagons into boxcars situated on the railroad. David Huscher was the first manager of the steam engine-powered elevator, according to a 2001 article in the Salina Journal.

“The elevator was built because it was a thriving community,” Linda Chubbuck said.

Just a village with a grain elevator

Huscher never had much population. However, at harvest, activity boomed.

The elevator’s owners went broke sometime in the late 1930s. Perry Chubbuck, who owned the elevator in nearby Rice, bought the Huscher elevator from the Reconstruction Finance Administration, Kent Johnson said.

Around 1950, Perry’s son, Ralph, became the manager and purchased the elevator a few years later, according to the Salina Journal.

Ralph’s grain career would span more than 30 years, Chubbuck said.

Huscher was a fun place to grow up, she said. But one terrifying memory occurred May 20, 1957, when a tornado came within a mile of Huscher. Chubbuck recalls she wanted to go to the cave for safety. Her father, however, was taking photographs near the school.

Those photos made the next day’s edition of the “Salina Journal.” They also were published in “Life Magazine.”

Huscher had a school. Chubbuck said she walked from the family’s home to the building down the street.

“It was one of the last one-room schools, district 57,” she said. “I went all eight years of grade school there. Shortly after it closed, sadly, it was torn down.”

Still a viable business

Chubbuck said she and former husband Johnson bought the elevator from her parents in 1981.

It was a tough time in the farm economy, she said.

“A lot of farmers were going bankrupt,” Chubbuck said. Meanwhile, elevators were pressured to get bigger. “Things were changing for small country elevators. It was during the farm crisis at that time. Railroads were getting deregulated. A lot of things transpired.”

The couple were forward thinking and changed the elevator from a full-time commercial operation into a seed-cleaning business.

When they divorced, Chubbuck operated it on her own.

“It was an excellent business,” she said. “I ran it as a single mom for nearly 10 years.”

Her children helped, including son Adam Johnson. He recalls one chore included cleaning the elevator’s pit.

“It was the worst you could imagine,” he said.

In 2001, Chubbuck sold the elevator to the man who helped her during the busy season, Max Pruitt. She moved out of Huscher and now lives in Lee’s Summit, Missouri.

Max sold the elevator and seed cleaning business to his brother, Mike, four years ago, Mike Pruitt said. Pruitt Grain remains operational at age 114.

The elevator isn’t the only thing keeping Huscher alive. Across the tracks is the United Methodist Church where parishioners gather every Sunday, Pruitt said.

Adam Johnson has his own memories of the 1980s and 1990s in Huscher. He and his brother and sister loved exploring the area and putting pennies on the railroad tracks.

Another story he tells with some reservation.

“The biggest memory I have of the church is one I say with some pride and guilt,” he said with a chuckle. “I shot the church light out with my .22. At the time of my admitted offense, I believe I had just learned about light pollution and was particularly offended at the light’s unnecessary existence. It was completely superfluous because I know there weren’t cameras and our house was literally the only one in view of the church.”

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].