Operation Ostrich: Raising one heck of a drumstick

Native to Africa, the ostrich is the world’s largest bird. Full grown, ostriches weigh 350 to 500 pounds. Known as extremely fast runners, they can sprint to speeds up to 43 miles per hour, according to National Geographic. If Olympians seem amazing, consider this: An ostrich can cover up to 16 feet in a single stride.

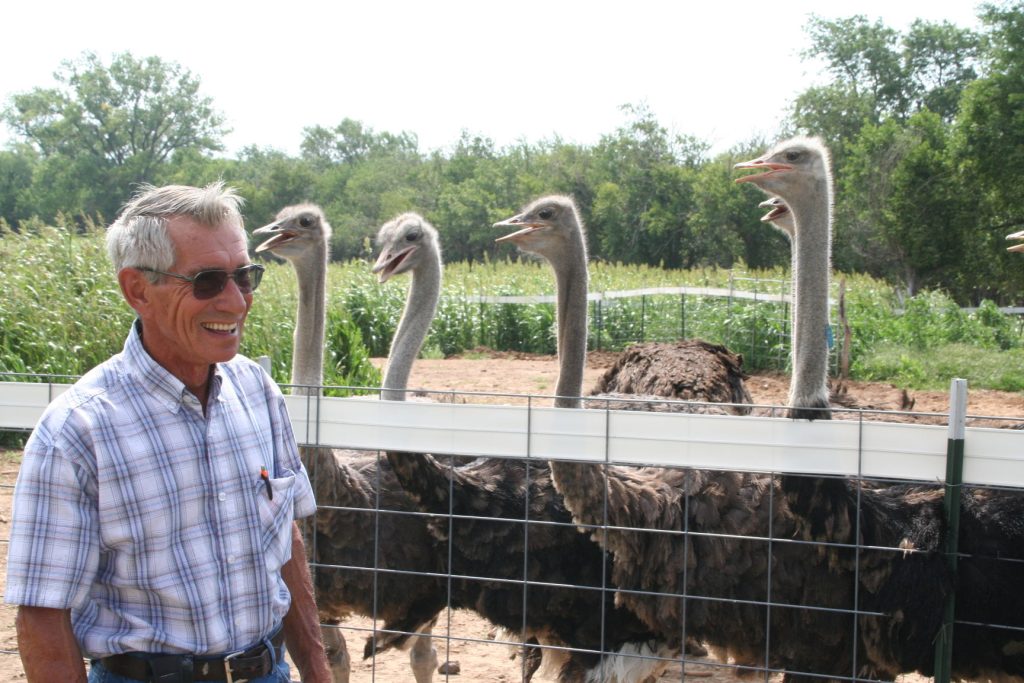

Incredible athletes they may be, but are they profitable as livestock? Stan Barenberg of Tescott, Kansas, says his operation is proof that ostriches can thrive on the Plains and provide a lucrative enterprise.

Barenberg bought a 5-acre property near Salina, Kansas, in 1992. Having grown up on a farm, he wanted to do something with the land besides mow the grass. He looked into cattle, hogs and goats, but with such a small acreage he didn’t feel he could produce enough livestock to make a profit.

Eventually he settled on the long-necked birds that cannot fly. The reasons were simple. Ostriches are opposite of cattle and hogs when it comes to manure. They do not produce a foul odor and the pens do not have to be cleaned or sterilized. Plus ostriches do not need to graze and they prefer an environment similar to a desert. For these reasons they are perfect for a small farm with just a few acres like Barenberg owns. Barenberg says he has never cleaned the pens in 20 years because the birds recycle the manure. He considers his operation an eco-friendly farm.

Additionally, unlike chickens, ostriches are hardy birds. Their average life span is 70 years. Barenberg says he has never medicated an ostrich and since few diseases are associated with their species, he does not vaccinate the herd. By cutting out a withdrawal period and the expense of medication, ostrich ranching becomes less complicated than some other industries. Consequently, since he does not medicate, the operation he calls Longneck Ranch is able to brand its product free-range and all natural, adding a premium to the meat.

“Hamburger is currently going for about $9 a pound and steak about $20,” he said. “Right now we are getting about $3 a pound live weight.”

Barenberg harvests birds at Krehbiels Specialty Meats in McPherson, Kansas. To meet an ever-demanding need for ostrich, Dean tenBencel of Nutri Tech meat retail buys the meat directly.

Back in fashion

“Back in the ’80s ostrich was big,” Barenberg explained. “Everyone thought they could make a fast dollar with them. At that time we had supply but we didn’t have demand.”

The demand issue, coupled with a sudden surge of ostrich ranchers rocked the slowly developing market at the time. The 1990s saw many ostrich owners abandon ship, selling off their fowl or even setting them free to survive on their own in some cases.

“In the mid-’90s people figured out they were going to have to work at this just like any other kind of livestock,” he surmised.

The secret to Barenberg’s success in the industry apart from hard work seems to be the time he started raising birds. Just as the supply dropped dramatically, Barenberg decided to join the game. He bought his first pair in 1995; with the fad over he was able to build his flock without so much competition. A truck driver at the time, Barenberg slowly added to his herd and retired from his trucking career in 2009. He now oversees 80 birds—some breeding stock, some growing chicks—and raises around 100 birds for slaughter each year.

He says in the 80s ostrich meat didn’t have many rules. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not inspect the meat, so there were no restrictions on health safety protocol. Since the FDA started inspecting ostrich meat in 2001 and the Ag Census first recognized the ostrich industry in 2002, the industry has built up a great demand for birds. The problem this decade is supply.

The supply issue is merely a symptom of the real problem. Because so many people quit when the market turned upside down, the main issue for those interested in starting an operation is finding birds to breed.

Barenberg estimates there are only two or three ostrich breeders in Kansas other than himself. Others raise birds in states such as Texas, California, Arizona and Oklahoma but without more people supplying the hefty demand for the meat he fears the industry won’t expand.

Part of this problem is their climate restrictions.

“Because they are a desert animal, ideal weather for the birds is 105 degrees Fahrenheit and no rain.” Barenberg said. “When it rains they stop laying eggs for a few days until it becomes dry.”

An ostrich probably wouldn’t fare well in a cool environment like that of Vermont or Massachusetts and with the bird’s sensitivity to rain patterns, Washington probably would be an ill-advised habitat. This component takes several states out of the ostrich equation.

However, it’s not just the temperature responsible for limited breeders. Just like any livestock endeavor, start-up costs exist. Incubators and dehumidifiers for hatching are a must for breeders but they come with a price tag. Barenberg suggests an alternative to a full-time ostrich operation.

“Farmers that have old feedlots they no longer use for cattle can feed out birds,” he offered. He said people can feed out 3-month-old birds, but the only problem is finding them.

Excellent omelet, stupendous steak

Although sometimes considered exotic meat, ostrich is very similar to beef. It is a red meat and Barenberg says if it were on your plate you couldn’t differentiate it from beef. Speaking from experience, he says it makes excellent tacos, spaghetti, meatloaf and grilled steak.

“You treat it like beef but you have to cook it slow because it’s so lean,” Barenberg explained.

Apart from the great taste, Barenberg says ostrich meat is 99 percent fat free and low in cholesterol. The American Ostrich Association compared nutritional information for ostrich, chicken, turkey, beef, pork, veal, duck and deer, finding ostrich to be lowest in calories, fat and second lowest in cholesterol next to turkey. “People are realizing the quality of the meat,” Barenberg said.

With its nutritional qualities, many cardiologists recommend ostrich to those experiencing heart problems. Although it seems ostrich meat has everything going for it, the main issue is not many retail stores sell it. Barenberg says some health stores and specialty markets offer the meat, but without a way for consumers to get hooked on his product the ostrich industry is stuck in limbo.

Although he champions ostrich meat, Barenberg is quick to clarify he does not expect nor hope for it to take the place of beef, but rather become an alternative for people with limited acreage or those who just want to try a diversified agricultural livestock.

Barenberg says hens reach optimal egg laying at 4 to 5 years of age and with lengthy life spans, most still lay eggs until they are about 40 years old. An average hen will lay about 60 eggs per year. Many unfertile eggs are sold for consumption. Scrambled seems to be the best way to cook them but Barenberg warns of the size. One ostrich egg is the equivalent of about two dozen chicken eggs.

Eggs, legs and toenails, oh my!

Ostriches are fed a mixture of corn, alfalfa pellets and soybeans. But even though he is raising a desert animal, Barenberg says the drought has been a major concern for his operation. With the cost of soybeans the last few years he has switched to distillers grains.

“Last year when everything was so bad I felt good that we broke even,” he said.

Birds being fed for slaughter are placed on a 15 percent to 17 percent protein ration. Barenberg estimates one ostrich eats about 6 pounds of feed per day. From full feed, the birds will gain 1 pound per day until they reach a year old and grow a foot per month until they are about 8 months old. As yearlings the birds weigh 250 to 350 pounds and are ready for slaughter.

“It’s not a get rich quick deal,” he stated. “You have to work at it and manage it right or you will lose your buck. If you get set up for it and manage it you can make decent money at it.”

Although the meat and eggs are profitable, they’re not the only parts of the bird that are harvested. Every part of an ostrich is used at slaughter. The meat is consumed, and the hide is used for boots and other leather products. The feathers are used for fashion accessories and since they do not conduct electricity, they are used to make dusters and brushes. Plus if you are looking for the perfect gift, ostrich toenail jewelry is available for purchase.

However, not every ostrich is raised for feather, leather and meat; just like some cattle are raised for milk not meat, there are categories of ostrich. Barenberg says there are three types of ostrich. He says the blacks are the smallest and gentlest of the three and are mainly raised for their feathers. The blues are the middleweight birds, which produce good eggs. The reds are the biggest of the ostriches. They are the meanest bird and produce fewer eggs. Barenberg says he has a cross between reds and blues to hopefully achieve larger birds, better eggs and a friendly disposition.

Imagine if Hitchcock decided to use ostrich instead of seagulls and sparrows in “The Birds”—a pretty scary thought. Although ostriches are often labeled as aggressive animals, for the most part they are docile. Barenberg says learning how to deal with an ostrich appropriately is the key to success. He has learned firsthand what to do and not do when handling an ostrich.

“You have to think different when you handle them,” he said. “You don’t use a hot shot on them and you don’t herd them around like cattle because they can hurt you.”

He has learned to adapt to the birds and treat them with respect rather than try to change the way their minds work. One tip he divulges is to stay behind an ostrich if possible.

“Stay away from the front because they can only kick forward.”

Contrary to the idea that ostriches are fierce predators, instead most of them are easily frightened creatures. To combat the risk of injury to the birds or fences, Barenberg protects the birds with a Great Pyrenees dog.

After almost two decades of ostrich ranching, Barenberg is about as close to an expert as they come. He doesn’t plan on exiting the ostrich business anytime soon. Eventually he hopes to purchase more land and expand his flock. As for Stan the ostrich man, he has found the perfect nest egg.

“People got burnt with these birds in the ’80s,” Barenberg said. “But things have changed. We are looking for people to get into the ostrich business.”

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached by phone at 620-227-1871 or by email at lvilhauer@hpj.com.