A fight in the field changed one Kansas farmer’s way of thinking and is saving the Ogallala Aquifer

Water Technology Farms show how spiraling technology is making a difference on the semi-arid High Plains, allowing irrigators to shut off when the crop doesn’t need watered

In the end, it came down to a fight in the cornfield that convinced Dwane Roth to change his way of thinking.

Up until that point, “I was driving without my headlights on,” the Finney County, Kansas, farmer admitted. Back then, he had the same mentality as a majority of irrigators in semi-arid western Kansas.

Roth translated the region’s high-yielding corn and economic vitality to the need to continually water his crops. So, rain or shine in the heat of summer, his irrigation systems would churn out water from the shrinking underground Ogallala Aquifer by the gallons.

On the outstretched, treeless landscape, the reminders of this philosophy came daily.

“You’d see the lights on the sprinklers blinking when you were up here in the mornings and it was dark,” Roth said. “I’d think ‘oh (shoot), I have to start my sprinkler.’”

He couldn’t see another way of doing things in an area where annual rainfall is 19 inches a year. Irrigation is like a security blanket.

It wasn’t that the dwindling aquifer and whether it would sustain another generation of Roths didn’t concern him. The reality of the situation hit home when he returned from the Army to farm in the early 1990s. He picked up a National Geographic that featured a neighbor talking about the issue.

Roth said he was always mindful of how much water he was using. He always tried to use a little less than he thought he needed. In 2016, he implemented technology in the field—soil moisture sensors—but Roth didn’t trust them. Midsummer, when it was hot and the corn was curling up, Roth, like his neighbors, turned on the pivot.

It would take the battle with the field technician, who questioned why the system was running, for Roth to come to a realization he might be wrong.

“He said ‘Look….Here’s what’s going on.’”

And, peering at a computer screen, Roth embraced what might seem like an unfathomable concept in western Kansas—especially when you can’t see what is happening underground.

Sometimes his crop isn’t thirsty.

Changing mindsets

Two years later, on a hot August afternoon, Roth stood his cornfield, watching as other farmers gathered to learn about the water-saving technology that is transforming his farm.

“I was probably the biggest naysayer of about anybody out here about this technology,” he told them.

Now Roth is hoping to change the mindset of his peers across a landscape where corn is king and the Ogallala Aquifer—the ocean underneath the High Plains—has been keeping the decades-old farm economy going.

Roth is promoting both management and technology practices to help him use less water and, in turn, extend the aquifer’s lifespan.

In 2016, Roth and the Garden City Company established one of the state’s first Water Technology Farms—a demonstration farm that showcases various irrigation technologies to maintain production but with reduced irrigation.

Roth’s Water Technology Farm makes up 10 circles of crops and is designed to show the effectiveness of the different water-saving technology, said Mike Myer, a commissioner with the Kansas Department of Agriculture’s Division of Water Resources.

The farm features three water applicators—Dragon-Line, iWob and bubblers—at 30- and 60-inch spacing. Meanwhile, he is testing six different soil water sensors, which reads the amount of moisture in his fields. The system is connected to his phone and computer, which can send him an alert if the crop needs water.

The field also has been mapped to identify management zones and locate where the soil water sensors could be most effective. And, he is cutting back voluntary on his water use. Roth enrolled the technology farm into one of the state’s new Water Conservation Areas, pledging to cut back 15 percent of his water use.

The results are promising.

For instance, on his tech farm, he cut back pumping from 12 inches of water to 6 inches. His cousin, who has circles next to him, used 16 inches.

“They used 10 more inches,” he said of his cousin. “I had a probe, and they didn’t. I grew 242-bushel corn. They grew 230. And we are right beside each other.”

Do the math, he added. He made $55 an acre more, or $7,000 more for the entire circle.

“Plus, I didn’t pump that water,” he said.

Maybe the information is enough to convince others that the technology in his cornfields is working. While changing perceptions isn’t easy, Roth stresses it has to happen.

Changes needed

Underlying eight states across the Great Plains, the Ogallala provides water to about one-fifth of the wheat, corn, cotton and cattle production in the United States. It’s also a primary drinking water supply for residents throughout the High Plains.

But the aquifer that gives life to these fields is declining. It has taken just 70 years of irrigation to put the western landscape into a water crisis.

With his own water levels declining, Roth wants to make sure there is water for the next generation, including his nephews who recently returned to the farm.

Roth had been interested in exploring better ways to apply water, which lead to a call to Troy Dumler, manager of the Garden City Company. Roth farms some of the company’s acreage.

That led to talks with Kansas State University and a meeting with Tracy Streeter, director of the Kansas Water Office, about implementing one of the first three Water Technology Farms.

The technology farm concept came out of a working blueprint developed by state water officials to sustain Kansas’ water resources, Streeter said. They heard time and again that irrigators were interested in adopting the technology, but wanted to see if it worked. The idea was to develop field-scale technology farms for such modeling.

Many change their attitudes when they see the technology really works, he said.

“What we see is in year one, maybe some skepticism,” Streeter said, but by year two and three, producers understand how to read the data and what it is showing.

“You hear this over and over again, ‘I now believe them. I trust them. As a result, I’m able to leave my sprinklers off longer than I thought I would. I started pumping later than I thought I would.’

“They are just starting to get confidence,” he said.

Technology works in the field

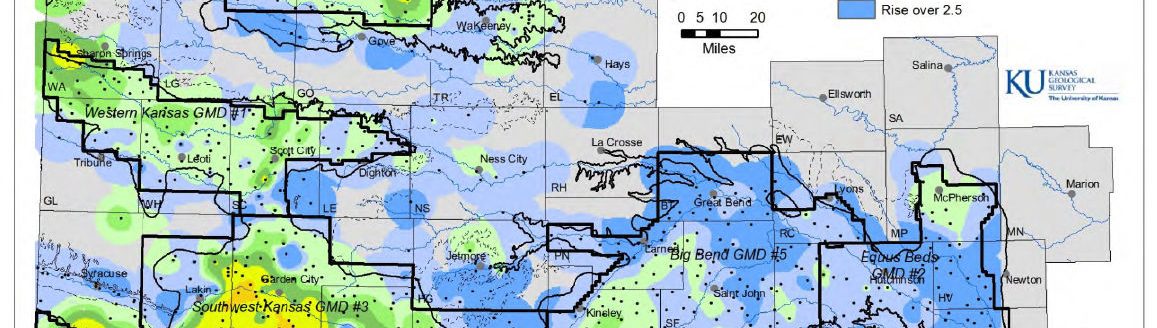

Kansas now has 10 Water Technology Farm projects on more than 35 fields overlying the High Plains Aquifer, stretching from northwest Kansas to Wichita, according to the Kansas Water Office.

The Kansas Legislature allocated money for more technology farms last session, he said.

Meanwhile, the state also has 17 Water Conservation Areas. A handful of applications are pending approval with the Kansas Division of Water Resources.

The areas are a good tool to extend the life of the aquifer, said Myer.

The conservation areas allow water users, or groups of water users, to voluntarily restrict their water use, but with more flexibility and less red tape. Those enrolled set up water budgets, operating under a five-year allocation that can be banked during wet years and used more during droughts, Myer said.

Such tools are especially crucial in areas of deeper decline. For instance, western Finney County where Roth farms has average drops of 10 to 15 foot a year, he said.

“You can kind of project when that water would run out or no longer be practical to try to utilize,” he said. “If we can slow down withdrawals, we can extend that time frame.”

The Garden City Company has 7,000 acres enrolled in a conservation area—which includes acreage farmed by Roth. The company has a five-year plan to reduce its current water right authority of 13,000 acre-feet a year to 5,000-acre-feet a year, he said.

Thanks to rain and good management, the farms across the company’s acreage have only used about 20 percent of the five-year allocation, he said. Roth’s farm is operating on a 1,200-acre-foot budget. Over the past two years, Roth has only pumped about 600 acre-feet.

“He is well below his projected budget for this two-year period,” Myer said. “He has basically saved over 50 percent of his two-year allocation.

“That speaks to the technology that has been incorporated here,” he added.

Water tech frontier

Agriculture is on the cusp of a water technology revolution, Roth said.

“We have done it with tractors, combines, sprayers, but we haven’t done it full-bore with water,” he said.

Jonathan Aguilar, water resource engineer with K-State Research and Extension based in Garden City, Kansas, said in 2012 about 10 percent of farmers had sensors, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service. He estimated the number has grown to about 20 percent.

“I’ve been talking to dealers, and they said their sales have gone up two or three times,” he said.

Streeter said one northwest Kansas dealer told him producers making one fewer irrigation pass in their field alone—thanks to the technology—will pay for a system.

“It’s groundbreaking,” he said.

Many groundwater management districts have cost-sharing programs to help producers pay for the technology. But while it is growing, Aguilar thinks the number of farmers actually using them might be low.

They just don’t trust it, he said. Those producers are still going by a feeling of when it is time to turn the sprinkler on.

He said he talked to one farmer who implemented it the first year but essentially disregarded the readings. Once he got used to it, he was using it the next year.

“I understand it,” Aguilar said. “Anyone who has new technology, it takes a while before they are able to really be confident about that technology. Dwane was that way, too.”

That’s where technology farms come in, he added. Irrigators can see how the systems are actually working.

He said Roth’s six brands of sensors range from cheaper to more expensive, but all provide a good eye on what is happening underground, Aguilar said.

“Sometimes they just need confidence to turn off the system,” he said. “Sometimes it affects their health. They know they can sleep better if they have done the right decision.”

Roth said his fields are a good example of what technology can do. By not overwatering, he is able to better utilize nitrogen and phosphate, which before, were being pushed away from the crop’s root system. He’s still capturing good yields all the while maintaining profit.

However, he admitted, as he stood beside his fields where water technology is spiraling, even with the all the proven data, some are unwilling to change.

“Some people oppose it,” he said. “They think reducing water will harm their crop and bottom line.

“I’m 52,” he added. “I wish I had this technology when I was 25. Imagine the water we could have saved if we had started 25 years ago.”

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].