Weather experts, climatologists, university researchers and other drought experts hosted a webinar Oct. 24 to give listeners an update on the long term drought and how El Niño may influence temperature and precipitation in the southwest region of the United States.

The webinar series is a collaboration of NOAA/NIDIS, National Weather Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, state climatologists, universities and others.

Gerry Bell, research meteorologist, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Climate Prediction Center, said currently much of the region is in an El Niño watch.

“That means conditions are favorable for the development of El Niño,” Bell said. There’s a 70 to 75 percent chance of El Niño this winter. In fact, conditions are moving progressively more toward El Niño week by week.

Bell said for the arid southwest, El Niño is often crucial for bringing beneficial winter rain and snow to build up the snow and ice pack.

“This increased precipitation often plays a critical role in helping to relieve or even eliminate drought in the southwest,” Bell said. “El Niño is a major player in the moisture sources, winter time moisture for the southwestern U.S.”

To understand El Niño, you first have to know what it is, according to Bell. El Niño and its counterpart, La Niña, are opposite phases of a very prominent climate pattern and that climate pattern is called the El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO for short. These are naturally occurring climate patterns and are related to variations in the Pacific Ocean temperatures in a particular area—along the equator between the international dateline and the west coast of South America.

“It’s a tropical climate phenomenon that is large enough to affect our weather pattern,” Bell said.

And affect it does—bringing with it wind, storms, hurricanes, jet streams, temperature and precipitation among other things.

“But the key thing to keep in mind is that all El Niño’s are not equal. Some are stronger, some are not as strong,” Bell said. “So the impacts vary from that one El Niño to the next. They vary in scope and intensity based on the strength and spatial extent of the event.”

As far as the winter forecast goes, that’s important to keep in mind.

“If there’s uncertainty in predicting the strength of El Niño, there’s going to be some uncertainty in the winter prediction,” Bell said.

The typical life cycle of El Niño or La Niña is nine to 12 months, and, on average, they occur every three to five years. They often develop in mid- to late-summer or fall. Bell said in summer and fall the events occur mainly in the tropics, with “not a lot of impacts in the United States other than with hurricanes.”

“The winter into the spring is when we in the U.S. have our most significant impact,” he said. “Impacts on the jet stream, the storm tracks, storm locations. As I mentioned temperature, precipitation, rain, snowfall, snow pack.”

They also play a role in drought formation and intensification and relief, with the last one being particularly crucial for the southwestern U.S. The Four Corners region has been a virtual bull’s-eye for drought most of 2018.

Bell asked, “Why does El Niño and its counterpart La Niña affect our winter weather?” It has to do with how they affect the tropical rainfall patterns.

“El Niño and La Niña alter the normal patterns of tropical rainfall and convection,” Bell said. “That deep, heavy tropical rainfall and thunderstorms basically from Indonesia all the way to the west coast of South America.”

It’s spread a distance of more than half way around the globe, and this is why they have such strong and extensive impacts on weather patterns. La Niña has the opposite pattern—it’s wetter than average in Indonesia and the western Pacific and drier than average more centered near the dateline and parts eastward.

“These rainfall patterns are important because they directly affect the jet stream,” Bell said. “These are such prominent rainfall patterns that they help to affect the intensity and extent and strength of the jet stream.”

Bell said winter weather is controlled by jet streams and El Niño and La Niña affect jet streams, therefore they affect weather in the U.S. The Pacific jet stream is the main driver for Pacific Ocean storms coming into the United States. With El Niño, the Pacific jet stream is shifted south of normal and is extended more eastward toward the southwestern United States. Normally the jet stream comes into the U.S. up near Oregon and Washington state.

“This is a significant southward shift of the jet,” Bell said. “Where the jet stream goes so goes the storms. With the jet shifted south, so is the storm track and as a result we have stormier, wetter and cooler than average conditions across the southern part of the U.S.”

Bell said it could mean drier than average conditions in the central U.S., and warmer than average conditions across the northern U.S. and Canada. With the same jet stream patterns, the polar jet, which brings some colder air into the country has shifted much more into Canada resulting in fewer artic outbreaks.

“It’s these combinations of these jet streams that give the warmer than average conditions across the north, but it’s this Pacific jet stream that is the main factor controlling the weather and storminess in the southwest,” Bell said. “With El Niño we look forward to that because wetter, stormier, more snow pack across the southwest.”

Bell said because the storm track has been expected to be south of normal, it will likely be wetter than normal for areas stretching from southeastern California all the way across the country to the Carolinas and up into the mid-Atlantic.

“Fortunately this is likely wetter than normal conditions for severely drought stricken areas, especially in the Four Corners region,” Bell said. “Now conversely because that drought has shifted south, we’re expecting drier than average conditions up into the northern plains and also portions of the north central Midwest.”

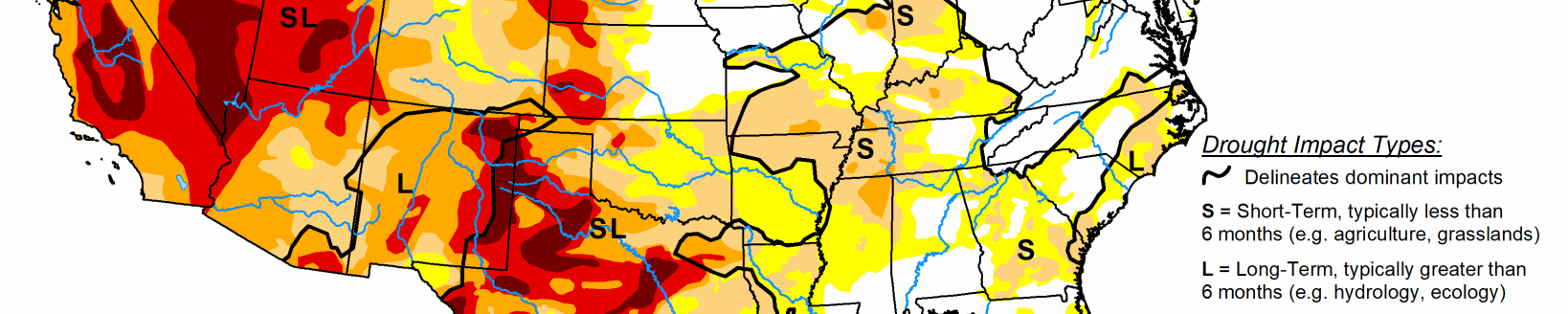

According to drought conditions as of Oct. 16, the persistent drought in the Four Corners region, as well as extreme drought into Oregon, Washington state are forcing residents, and farmers and ranchers to make some tough choices.

“A lot of the western U.S., basically you can see is some sort of moderate to severe or extreme drought,” he said. “And only very limited regions of the west are not in a drought at this time.”

Based on Bell’s predictions, there could be some drought relief and drought removal.

“If El Niño develops, it is expected to significantly improve drought in the southwest U.S., but not all of the really bad drought area,” Bell said. “It’s also expected to relieve drought from northern California up through western Oregon and into western Washington state.”

Bell also doesn’t expect any new areas of drought to develop this winter. The large areas suffering drought currently are expected to improve or end. However, for those areas in eastern Oregon, down through Utah, and southern California the current drought conditions are expected to persist.

For more information visit the National Integrated Drought Information Systems website at www.drought.gov/drought/.

Kylene Scott can be reached 620-227-1804 or [email protected].