Sharp turn to cold brings threat of fescue foot to beef cow herds

Odd fall weather and fescue pasture growth set up the potential for poisonous pastures causing fescue foot in cow herds.

Fall growth after a drought produces more toxins in infected tall fescue grass. The poison develops after rains start regrowth following a drought, says Craig Roberts, University of Missouri Extension specialist.

Roberts urges herd owners to keep close watch on their cows. “At first sign of a limp, take the cow off the toxic grass,” Roberts says.

“Make plans for alternative feeds,” he says. That includes pasture without Kentucky 31 fescue. On most farms, fescue remains the most-used forage. It is hardy because the toxin protects the plant from pests.

Another choice is to confine and feed limping cows on grain and nontoxic hay. Ensiled fescue hay should be avoided. Plastic-wrapped moist hay, or balage, preserves toxins.

Several factors worsen fescue toxicosis causing fescue foot, Roberts says.

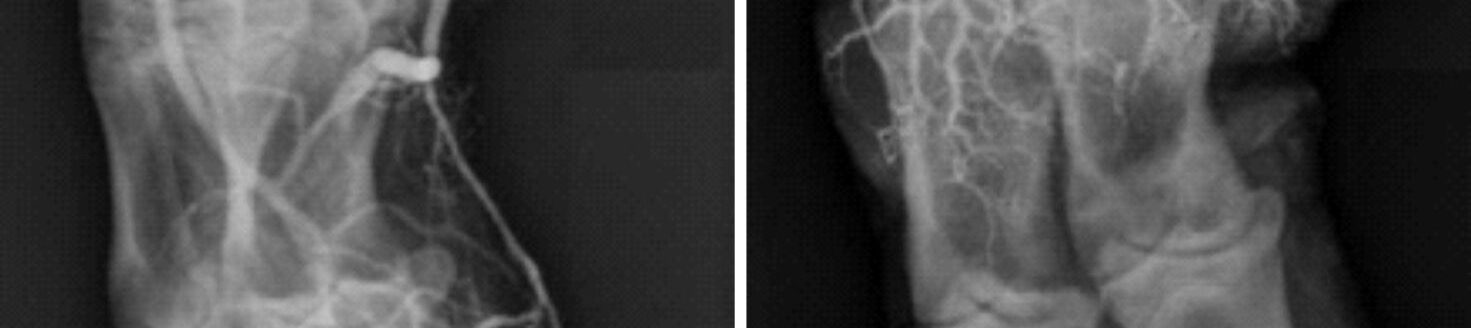

Ergot alkaloids produced by a fungus in infected fescue restrict blood flow in cattle. Fescue foot develops in long cold spells. In cows, low blood flow to feet allows frozen hooves. In worst cases, hooves fall off.

Injured cattle cannot walk to graze pastures. They stay in place and die from lack of feed. Roberts says, “We’ve known of this syndrome since 1994. This year may be worse than usual.”

Spreading extra nitrogen fertilizer in the fall to boost grass growth also boosts production of toxins, he says.

In a normal year, extension specialists recommend adding 60 pounds of nitrogen. This year, after the long drought and shortage of hay, many farmers added 80 pounds of N. There’s been good grass-growing weather this fall, Roberts says. The extra growth brings more toxins.

The trigger can be continued low temperatures. “A cold snap of one day isn’t a problem,” he says. “A week of freezing could be a disaster.”

There’s no cure for fescue foot, but prevention works.

Herd owners who converted toxic fescue pastures to a novel-endophyte fescue need not worry. “Fall growth is a bonus on new pastures,” Roberts says. “We see benefits on pastures that have been converted.” There are no toxins and forage quality is higher with the new fescues.

More nitrogen fertilizer on novel-endophyte grass brings more feed.

Prevention includes not grazing fall-grown fescue too short. Recent research shows most toxins in the fall stay in the lower 2 inches of the fescue plant.

Another preventive plan is to feed winter hay in fall cold spells. The pastures left standing in winter decrease in toxins with time. By January there will be less poison in the grass. Stockpile can be grazed late in winter with few problems.

Management-intensive grazing with quick rotations through paddocks helps prevent short grazing. “With rotational grazing, cows are moved before they grub grass into the ground,” Roberts says.

Cool-season grasses have an advantage, growing rapidly two times a year: Growth in spring and fall adds to grazing seasons.

Spring grazing requires caution, as toxins concentrate in seed heads and stems. Those are easily grazed by cows. There are no seed heads in fall growth.

The only cure for fescue toxicosis is killing infected pasture and reseeding to a novel-endophyte fescue.

Schools teaching reseeding were held in Missouri for years. Now those schools are held in the fescue belt across the Southeast. More schools will be in March 2019, Roberts said.

Schools cover six states from Missouri southeast to North Carolina and Georgia. Times and places are on the Alliance for Grassland Renewal website. Go to grasslandrenewal.org/education.htm.

For more than 100 years, University of Missouri Extension has extended university-based knowledge beyond the campus into all counties of the state. In doing so, extension has strengthened families, businesses and communities.