Cheap food: Who pays the price?

As I was fueling my pickup in rural Nebraska, I saw the sign for this grocery store/fuel shop promoting eggs for 89 cents a dozen. While I fully understand the concept of a “loss leader,” something about this really shifted my windshield thoughts into overdrive.

We brag about the United States because we spend less of our disposable income on food than people from anywhere else in the world but who has reaped the rewards for those low food prices?

Since 1832, my family has made a living in this country producing food, fiber, pharmaceuticals and fuel from the land. In those early years, about 80 percent of the U.S. population was involved in farming while we are at about one-half of 1 percent today.

In 1960, just short of 18 percent of the U.S. consumer’s disposable income was spent on food. The U.S. Department of Agriculture now says that number has hovered right at 10 percent since 1995. What can you buy now that costs the same amount as it did in 1995? Can you name one thing other than food?

In the U.S. in January 2017, the average bill at the checkout was 12 percent higher than in January 2016 and at its highest since early 2015. We can break the staples down globally, including five commodity groups—cereals, vegetable oils, dairy, meat and sugar. Sugaring your coffee costs 45 percent more than in January 2016, while adding milk costs 33 percent more, and the price of drizzling oil on your salad has increased by 34 percent compared to last year. Only meat has remained relatively stable, increasing by only 8 percent.

The World Food Programme estimates that people in the developing world spend 60 to 80 percent of their household income on food. Since 97 percent of the world’s population lives somewhere other than the U.S., these price increases have an even greater effect on them.

I have never been one to sit back and blame others for the hand I have been dealt. However, I think the time has come for national discussion about the sustainability of our country’s food production system, especially when you read these statistics from the USDA’s Economic Research Service:

For a typical dollar spent in 2016 by U.S. consumers on domestically produced food, including both grocery store and eating out purchases, 36.3 cents went to pay for services provided by foodservice establishments, 15.2 cents to food processors, and 12.4 cents to food retailers. At 3.9 cents, energy costs per food dollar were below the 4.6-cent average for 1993 to 2016.

The food-at-home consumer price index rose 0.3 percent from the second quarter of 2017 to the second quarter 2018. Although egg prices were up by 19.7 percent over this period, eggs represent a small share of total grocery spending. Prices for fresh vegetables fell 1.8 percent, nonalcoholic beverages were 0.8 percent lower, and both dairy and other foods fell by 0.2 percent, moderating overall food-at-home inflation.

A presenter at a global food meeting in Dublin, Ireland, some years ago made the statement that U.S. consumers don’t pay enough for their food. I shared how proud we are of that accomplishment, but I am not sure I am still so proud. We really need to take a hard look at who is reaping the rewards for what farmers have worked hard to accomplish—healthy, affordable food for the nation. Dairy farmers are going out of business, produce is left rotting in the fields and commodity prices are still in the tank. Who is winning?

We have a White House administration with a business background, but we are not seeing enough movement toward freeing ag business from the grasps of government. I have always been told that we have cheap food because that gets people elected. If you want to see where that gets you, look at what happened in California regarding Proposition 12; voters supported another law that will make more hungry people in the state.

So why are nearly 12 percent of all U.S. households considered food insecure at a time when farmers are struggling with overproduction? One reason for that is people have learned to farm the food welfare system. While this column isn’t long enough to address all those problems, let’s be honest and admit that we still have too many in ag farming the government crop subsidy system as well.

I believe the real answer to all these questions lies in something I learned in high school. Perhaps the nation’s ag producers, leaders, politicians and consumers could use a refresher as well:

I believe in less dependence on begging and more power in bargaining; in the life abundant and enough honest wealth to help make it so–for others as well as myself; in less need for charity and more of it when needed; in being happy myself and playing square with those whose happiness depends upon me.

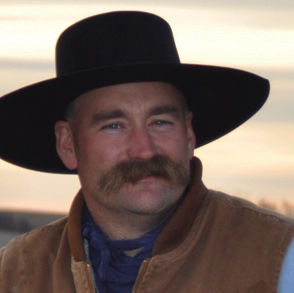

Editor’s note: Trent Loos is a sixth generation United States farmer, host of the daily radio show, Loos Tales, and founder of Faces of Agriculture, a non-profit organization putting the human element back into the production of food. Get more information at www.LoosTales.com, or email Trent at [email protected].