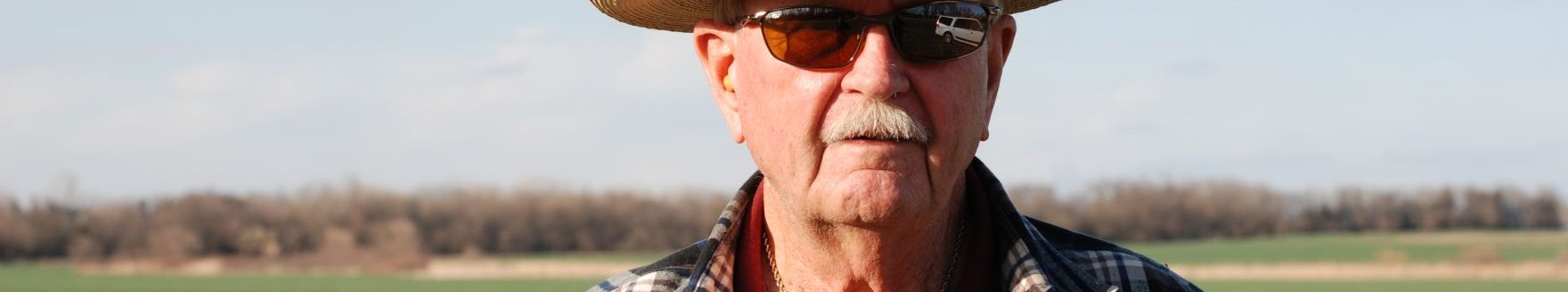

Douglas County farmer Scott Thellman traveled three hours, despite forecasts of snow and sleet, to be at the meeting.

And, on a cold, late February morning, he wasn’t alone. More than 300 others from all corners of Kansas and surrounding states gathered at the Kansas State Fairgrounds in Hutchinson—all with visions of a new source of green growing on their farms in the next year or two.

More than 80 years after it was outlawed, industrial hemp is back—or so reads the 2018 federal farm bill that recently passed. And in a struggling farm economy, Scott sees hemp as a crop that could help farmers diversify, become more sustainable and more profitable.

“Someday it will be as common as corn and beans,” the 28-year-old farmer said with hopefulness.

But Scott—a first-generation farmer who grows organic and conventional vegetables, along with traditional row crops and hay in the Kansas River Valley—admits while it may now be legal to grow industrial hemp, this new farming frontier won’t be easy. He and other farmers in the room expressed concerns, asking a litany of questions about management and state and federal rules as Kansas switches its regulations from hemp research to commercial production.

The goal was for farmers to find some answers during the daylong event, said Kelly Rippel, president of the Planted Association of Kansas and vice president and co-founder of Kansans for Hemp. The two groups, in conjunction with the Colorado-based Hemp Biz Conference, organized the Kansas Hemp Symposium Feb. 23 to help farmers gather information about the fledgling industry.

Rippel noted the 2019 and 2020 crop year would be more data gathering as farmers look at varieties and genetics, plus the establishment of processing and markets.

“We can tell there are people doing their research and doing their due diligence and trying to find out as much as they can about growing it,” he said. “The whole goal of this symposium is to help farmers understand whether it is viable, whether this is something good they can do.”

A look back at history

Industrial hemp was once a prominent crop in the United States.

The Declaration of Independence was drafted on hemp paper. At one time, Kansas was among the nation’s top hemp producers, said Peter Andreone, a cannabis business attorney from Overland Park.

But the industry began to disappear in the 20th century, he said. Hemp was doomed by the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which placed an extremely high tax on marijuana and made it effectively impossible to grow industrial hemp. During World War II, the U.S. Department of Agriculture campaigned with “Hemp for Victory” and allowed farmers to grow it with a permit.

Yet by 1958 there were no U.S. hemp fields. Rigid restrictions in the Controlled Substances Act brought the industry to a halt around 1970.

“Farming hemp was outright banned,” Andreone said.

With millions of dollars of industrial hemp imported from countries like Canada, a momentum to legalize industrial hemp began to grow in the early 2000s. The biggest development happened in 2014 when the farm bill carved out a definition that separated industrial hemp from marijuana, Andreone said.

Industrial hemp is defined as a plant that contains less than 0.3 percent THC, which does not produce a high. Marijuana, smoked for its hallucinogenic and medical properties, contains 10 to 100 times that amount.

Kansas lawmakers approved a research pilot program during the 2018 legislative session.

Then, the 2018 farm bill effectively took hemp off the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency’s list of controlled substances, putting it under the supervision of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Andreone said the current farm bill gives states three different options. While some states could prohibit hemp production altogether, the moving of hemp and hemp products through that state can’t be outlawed because hemp is now federally legal.

States also have the option of doing nothing and wait for federal regulations to come online and adopt those policies, he said. Or, states can submit a state plan to the federal government.

Kansas Department of Agriculture spokeswoman Heather Lansdowne said state officials would be reviewing applications turned in by Kansas farmers to grow hemp under the research guidelines approved in 2018. The agriculture department, however, has drafted a bill that would allow KDA to develop a state plan for a commercial hemp program.

The House Agriculture Committee passed House Bill 2173 in late February. It has been referred to the House Appropriations Committee.

Lansdowne said while the March 1 deadline for state applications under the research program has passed, staff is still evaluating just how many applications the department received and how many acres might be planted in 2019. Rippel, who sits on the state’s Industrial Hemp Research Advisory Committee, said the committee would receive blind copies of the applications for approval.

Hindered by the unknowns

While it is now legal to grow hemp, there are still many restrictions and regulations that have some farmers concerned. They want more clarity before investing time and money in the state’s application process.

For example, farmers must grow certified seed, said Rick Trojan, who owns a hemp farm in Colorado and is vice president of Hemp Industries Association and a board member of Vote Hemp. However, one out of five seeds that are brought in from another environment—including Colorado—can test hot.

Farmers have to destroy fields that test over the THC threshold, he said.

But those issues should get easier as the crop becomes more established, Trojan said. More research will help create plants adapted to the region. Moreover, as more grow the crop, established processors and markets will begin to emerge.

Trojan stressed patience. He noted his operation started with feral hemp that he turned into a 4,000-acre operation.

“Know what you are growing for, adapt to your environment and allow time for you to understand what the crop will do,” he said.

What to grow?

For several farmers at the meeting numerous questions still loomed and that has kept them from applying for a 2019 state permit by the March 1 deadline.

At the top of the list is the potential the crop could test higher than 0.3 THC. That would mean they would have to destroy their entire investment.

“Where did that level come from and is it artificially low?” questioned Morton County, Kansas-farmer Darren Buck, adding he thought THC levels could be a few percent and still not be in the same category as marijuana.

Buck flew to Topeka during the 2017 Kansas legislative session to show his support for legalizing hemp.

“Everyone wants to get involved but there are just a couple elements holding them back,” said Aaron Cromer, who also farms in Morton, as well as Stevens County. “One is the marketing end of this deal. But we know we can contract product, and we have a baseline for prices we can receive.”

The other, he said, is the 0.3 percent THC.

“If it were 2 or 3 percent rather than 0.3 of a percent, it would be the same product and would buy the leeway needed for us to not be concerned about losing our capital,” he said. “I know a lot of folks are concerned about the 3 tenths of 1 percent.”

Cromer said Morton County economic development leaders are looking at a processing plant.

Buck said he was more likely to try hemp in Oklahoma. Under Oklahoma law passed last year, farmers, in conjunction with universities, can cultivate hemp for research and development.

“It is a very individual market, and it is because we are in the crop’s infancy,” Buck said. “That is hard because if I’m going to go out there and plant 80 acres, I’m not doing it until I have a contract.”

Rippel said potential processors were in attendance. So were seed dealers.

Matt Sawyer, who operates Schneider Feed, Lawn and Supply in Augusta, said he applied by the deadline for a distributors license. He already has been in contact with certified seed dealers in other states and countries. He hopes to begin selling and storing seed this year.

“I think, eventually, if we can get the infrastructure right, industrial hemp will take off,” he said.

Douglas County’s Thellman, however, is still exploring his options. One issue, he said, is everyone who is part of the hemp process on his farm would have to be listed on the application. He doesn’t start hiring until April and a change in the application would cost an additional $750.

“A lot of it comes down to the economics of it, the infrastructure behind it, the logistics of moving a potential product whether that is under contract or otherwise,” he said. “There are so many things that need to be clarified before it is something I would consider on my farm.”

But as those issues get worked out, Thellman only sees an upside.

“There are very few opportunities like this to jump into a new market for any crop,” he said. “It is very exciting and interesting to be potentially getting into the forefront of a new industry for Kansas that hopefully helps all farmers become more sustainable and increase farm income.

“It excites me to see a roomful of such diverse people converging on such as gross day weather-wise to learn more.

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].