Winter wheat farmers in several states have not had an easy winter. All eyes are on Kansas, Nebraska and Colorado as “a perfect storm” of historically low temperatures combined with severe dryness threatens new crop yield potential in the heart of the country’s breadbasket.

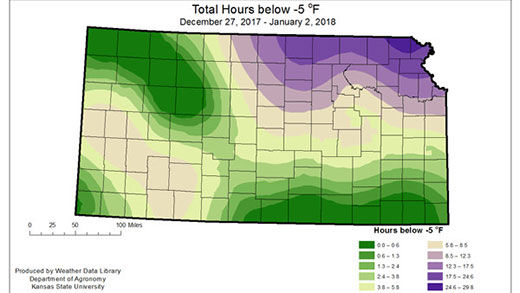

Producers in the Great Plains have seen sustained temperatures below 10 degrees Fahrenheit, low enough to cause serious concern about the crop’s ability to survive dormancy. Typically, snow cover and adequate soil moisture would help insulate the dormant crop, but this year has been anything but typical as severe to exceptional drought conditions persist from western Kansas into western Nebraska and eastern Colorado. Unlike lighter freeze damage, from which the wheat can bounce back under the right conditions, this year’s freeze event has the potential for “winterkill” in some regions, and ultimately challenge the final production volume.

“Today, there’s no way to tell the extent of the damage, but by mid-March when fields start to green up, we will know what we are facing,” said Justin Gilpin, CEO of the Kansas Wheat Commission.

Here is a look at the three states most concerned about new hard red winter and hard white crop conditions.

Kansas

According to USDA, as of late January 2021, the state’s topsoil moisture supplies were 21% very short and 34% short, 15 points worse than this time last year.

“We got the wheat up and growing, but do not have enough moisture to set brace roots,” said Gary Millershaski, a Lakin, Kansas, farmer and a U.S. Wheat Associates director. “We had a couple of inches of snow, but temperatures of 19 degrees F below zero tell me half the tillers might not make it.”

Though conditions are drier and colder in western Kansas, wheat farmers in the region were able to get the crop planted on time, which will help its ability to fight low temperatures, said Romulo Lollato, Wheat and Forage Specialist at Kansas State University. Later-planted wheat will have a harder time fighting the freeze.

“Right now, our main concern across the region is winterkill which could limit harvest potential,” said Lollato.

Nebraska

“In Nebraska, our concerns are poor emergence, weak stands and drought conditions,” said Royce Schaneman, executive director of the Nebraska Wheat Board. According to USDA, just 30% of the state’s wheat is rated good to excellent, down from 70% good to excellent this time last year due to substantial drought conditions.

The wheat is extremely susceptible to sustained freezing temperatures as parched soil and limited snow cover offer little protection.

“Moving forward, we need a good warm-up in spring, no late freezing and many timely rains,” said Schaneman. “If we have the perfect growing conditions throughout the season, we can expect an average harvest. We are off to such a poor start so given the current outlook, this could be a tough year.”

Colorado

“Winterkill has now become a major concern with last week’s extreme temperatures, down to 15 degrees F to 25 degrees F below zero,” said Brad Erker, executive director of the Colorado Association of Wheat Growers.

Looking ahead, Erker said the best weather for producers in Colorado would be a “big, wet snow” by the first week of March.

“Moisture to come could heal the situation but the timing of the moisture will be a big factor,” said Erker. “If we go too long into the growing season without moisture, we will start losing potential. We are in worse shape now than this time last year, and 2020 ended up being a very small crop for us. We can’t wait until the end of April for moisture or we will lose a lot of acres.”