Ehmke ‘nursery’ opens door for new weapons to squelch wheat streak mosaic, other viruses

Badly damaged wheat, striped in yellow and pale green, waved in a cool spring breeze one afternoon late last month.

Quiet was interrupted when farmer Trevor Tucker drove up in a mud-caked pickup truck. He parked along the gravel road north of Amy, Kansas.

Disgustedly gazing over the remains of what was a promising field before a swarm of wheat curl mites infected it with wheat streak mosaic and other murderous maladies, the bearded lad unleashed some angst.

“It’s hard enough to dodge hailstorms and early freezes,” said Tucker, 30, who grew up on the family farm he purchased a couple years back.

“Then you have this out here,” he said. “It’s not my wheat crop, but it’s upsetting even to see somebody else going through this.”

Perils from decades of the manageable virus are well known in Kansas. This time, wheat streak mosaic stained Marit Ehmke’s solo farming debut last fall, and continued into this summer’s harvest.

While initial results appear dire from the dying foliage that will produce little or no grain, there ultimately could be a brighter outcome to her first personal wheat streak mosaic experience.

“There is a silver lining, that we could be close to finding something that’s more resistant to the virus,” she said.

The dreaded wheat curl mite finds refuge in fields of volunteer wheat late each summer, floats on prairie gales for feet to miles, carrying wheat streak and other viruses to impale healthy new fledgling wheat plants.

There is no proof of where the virus originated other than it is believed to have migrated in, said Healy farmer Vance Ehmke, Marit’s father.

Someone was “negligent,” he said, and failed to eliminate the hosts—volunteer wheat—prior to the emergence of new-crop wheat.

Fixing the problem isn’t complicated, Vance said. Just kill the volunteer that emerges after every wheat harvest by spraying Roundup herbicide, before new crop wheat comes up in the fall.

“It’s a very low-cost herbicide,” he said.

Atrazine works, too, according to Tucker.

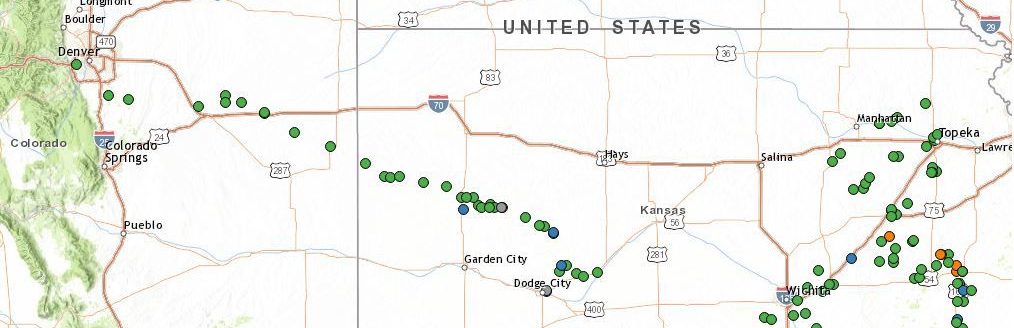

The search for mite migration lured U.S. Department of Agriculture and Kansas State University researchers to Lane County two years ago, where they planted thousands of test lines of wheat and other species.

It happened to be downwind and in the migratory path of enough mites to do major damage, creating a gound zero of destruction.

While the evidence spells doom, the death splat is interpreted as great news for the agriculture scientists.

“These plots couldn’t have been put in a better place for wheat disease in the state of Kansas,” Marit said. “You walk out there and it’s sickly yellow plants; really sad to see.”

Vance first noticed yellowing foliage last November before the wheat entered winter dormancy. As spring temperatures graced western Kansas, much of the test plots and a big chunk of his daughter’s wheat, appeared to have been wasted.

“It looks like the plants were hit with a flamethrower,” the veteran producer described.

Some of Marit’s wheat will yield zero, but other parts are OK and expected to yield 70 bushels to the acre.

“Not the whole field is decimated, but there will be a $16,000 to $30,000 loss,” said the rookie farmer who planned to use farm income to pay for her graduate school at Montana State University.

While wheat streak mosaic, triticum mosaic and high plains virus all will lower or eliminate yield, the expected field average will still be approximately 53 bushels to the acre, she said, too high to fetch a crop insurance settlement.

“Losses like this will make it very difficult for me to cover my cash rent as well as other production costs,” Marit said. “This is my first year farming, and I thought my biggest worry would be weather.”

Wheat streak mosaic has been a costly pain for decades in the state. It has landed some heavy blows in Lane County, according to Vance.

But these pesky viruses might finally have drifted too far in threatening Kansas’ staple crop.

The thousands of wheat and triticale test strips were planted in concert with Marit’s field of Guardian wheat with the sole purpose of confronting destructive viruses. Developed by Colorado State University, Guardian is among the most virus resistant on the market, but not even that line could completely fight off this wave of disease.

Some of the promising variety was “also hammered,” Vance said, and farmers in these parts knew they need more weapons.

When Mary Guttieri, research geneticist with the USDA-Agricultural Research Service, and Allan Fritz, a wheat breeder from K-State, visited earlier this spring, each found themselves standing on a mother lode of information, face to flag leaf with their longtime nemesis.

They’re on the case, along with researchers at CSU and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, to forge a recipe aimed at providing the best resistance yet to wheat streak mosaic and viruses of its kind.

Guttieri told Vance there were levels of damage in the plot so intense she had only seen examples in textbooks, never in person and so widespread. The devastation likely holds new clues in the battle.

“They wanted to get infected, wanted a real test, and, believe me, they found it,” Vance said.

An oil driller acquaintance of his said it looked like herbicide drifted on high winds over the plots and north end of Marit’s field.

“There is a good story here,” said Guttieri, who is part of the Hard Winter Wheat Genetics Research Unit on the K-State campus in Manhattan.

Because of these researchers’ mission, it’s never good news for your immediate future when the USDA asks to plant test plots on your farm, Vance said.

“You sure don’t want these plots showing up across from your field, because if they’re there, you’re doing something wrong—big time,” he said.

This time may be different.

“I’m really excited about how good the new things look,” Guttieri said, referring to the resistance showed by many of the wheat and triticale plots.

She and Fritz have collaborated extensively on field trials.

“We both have sought to have a field-testing environment where mite-vectored viruses are endemic, usually present already, where we don’t need to introduce them,” Gutierri said. “We really wanted a field environment where we could screen for tolerance or resistance to these viruses, and where we did not have to create a virus problem. It’s already there.”

They got what they were after on the Ehmke farm.

“We got all the virus we could get in a natural environment,” said Fritz.

“We’re looking at the cornucopias of these viruses in their own environment,” he said. “We are able to look at all of our breeding materials and see what stands up to that intense pressure, identify genetic material, and find sources of resistance that are best equipped to deal with the virus epidemic that we get in western Kansas.”

Combined, the scientists planted more than 3,000 breeding lines of wheat on what is called a “nursery” on the Ehmke farm. Guttieri’s plots were mostly from germplasm that she is targeting for resistance to the viruses.

“We’re talking about things that could someday become (wheat) varieties,” she said. “For me to see what was in that nursery was very rewarding. I saw the work I’ve been doing, built upon a strong legacy at Kansas State, nearing the point of really providing benefits to the growers.”

Fritz also mentioned Guorong Zhang, a wheat breeder at the K-State Research Center near Hays, Kansas, who is doing a lot of work on virus resistance.

The Ehmke nursery held two lines that are resistant to triticum mosaic, for instance, while one is not, Fritz said.

“It clarified a future strategy,” he said. “Beyond that, Mary has triticale out there.”

While there was “quite a lot of the virus” in the triticale,” Fritz said, “it didn’t do any damage to the plant.”

The process is long and meticulous, as breeders will screen as many as 50,000 lines in one season.

Only one may become a variety released to producers.

“We worked to identify a variety that has the material to become a commercial variety,” Guttieri said, and the Ehmke farm “is a great place to do selections in an environment where we have varieties where we see resistance.”

Each plot is judged from weak to strong.

“You’ve got to sort through them all,” she said. “It’s really helpful in the sorting process, to look at the diseases you’re breeding for.”

What was planted in the fall of 2019 on the Ehmke farm showed some of the desired results, but the 2020 plots revealed a much higher level of strong disease pressure.

“This year, we found it,” Guttieri said. “Last year, we always had some, but the infection was not as severe. Most of what I planted in the field came from what we selected on the Ehmke farm the previous year.”

“The difference from resistant or tolerant wheat to susceptible was dramatic,” Guttieri said. “It is very easy to effectively discriminate between the rows with a good level of tolerance and those that didn’t.”

The viruses were present in the plots, she said, and the breeding material showed a range of high resistance to being tolerant of the viruses.

“They were working very well, and some look great,” Guttieri said “We hope to find something with high enough yield and sufficient quality to become a commercial variety to address the challenge of these viruses.”

Varieties planted in 2020 on the Ehmke farm are interpreted as “a good step forward” toward a better solution than what’s currently available, Guttieri said.

Another surprising outcome to the 2020 plots was the resistance found in the triticale varieties planted on the test plots.

“I always put triticale in the first row (of each plot), and it looked good when Vance sent me the photos,” she said.

Those results led to Guttieri reaching out to Katherine Frels, an assistant professor in the agronomy department at UNL, who is joining in the research on the Ehmke farm.

“Mary’s triticale micro-lines were some of the best looking stuff out there. That’s something else for the plant breeders to put in their toolbox,” Frels said, and saves time as well.

“It takes seven to 12 years to get a (resistant) variety out if we start from scratch,” she said. “If we start with other forms of proven resistance (i.e. triticale), we are ready to roll out new things when we need them.”

Wheat streak mosaic is evident in Nebraska, Frels said, but not as severe as other areas, such as Kansas.

UNL boasts of having a major triticale breeding program in the northern Great Plains, she said, and the plot in Kansas could provide information to learn if the crop’s resistance to the viruses can be crossbred into wheat, and in the process improve triticale.

“We know the triticale acreage is growing, and we want to make sure we put out the best triticale,” she said. “I’m really excited about the opportunity to do this.”

She is reaching out to Punya Nachappa, a CSU entomologist.

“Our goal in working with her is to understand whether we have resistance to the wheat curl mite, the vector that spreads WSM,” Frels said. “We hope to put some lines out next fall and really screen what is resistant, or just tolerant. If triticale still gets infected, but doesn’t show symptoms, that means it’s unlikely the virus is going to mutate and change to overcome that resistance, and the plant is basically able to fight it off.”

Frels added that the tiny mites can easily avoid pesticides by finding places to be well-protected.

“Once we get (triticale lines) out in the field, we will work on screening in the greenhouse to better understand how the mechanism works,” she said. “We’re really hopeful we might find something useful to the wheat breeding community.”

Fritz is all for the collaboration and further study at the Ehmke farm.

“Pursuing triticale might give us sources of resistance that we can mobilize faster,” he said. “That nursery in Lane County gives us hope to look at real-life conditions.”

The big picture carries some potentially major upside for enhancing wheat production in the Great Plains, researchers agree.

“It’s a critical tool,” Fritz said.

Grim scenes on the Ehmke farm offer gleams of hope, despite the punch of reduced yield potential.

“Theoretically, it might be worth the loss,” Marit said. “It’s resistance we might be looking for, and if they find it in that field, that would be incredible.”

Aiming for a master of fine arts degree in science and natural history filmmaking, her personal experience might also prove fruitful in academia; maybe even a thesis project.

“A good story always has a problem and a solution,” Marit said. “This could be a topic for a documentary.”

Tim Unruh can be reached at [email protected].