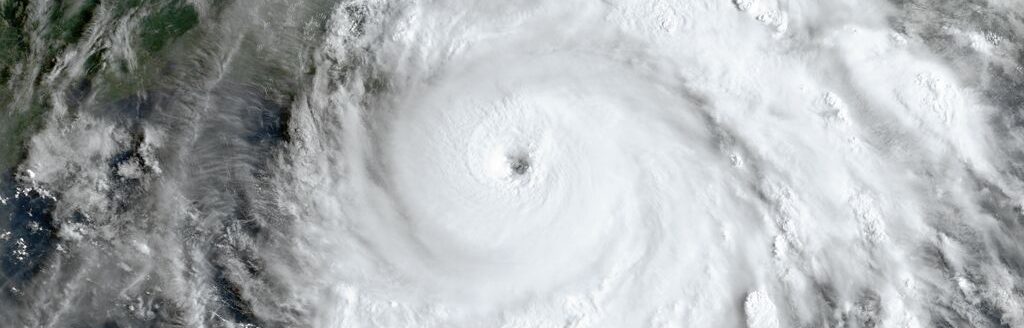

All grain movements to and from the New Orleans area have halted since the Coast Guard shut down the entire Lower Mississippi River in anticipation of Hurricane Ida, which made landfall Aug. 30, traveling up the west bank of the Mississippi River. The eye of the storm passed over Reserve, Louisiana. The storm scattered and sank many barges and other vessels, but assessment is just beginning as Coast Guard and other first-responder assets were focused on search and rescue efforts in the storm’s aftermath.

The Category 4 storm—whose 150-mile-an-hour winds were stronger than those of Hurricane Katrina in 2005—left more than a million people, including the entire city of New Orleans, without power and did tremendous damage as it smashed houses, toppled buildings and flooded some towns. Damage assessments are just beginning, but experts are already saying the final toll with be in the double-digit billions, at least.

Ken Eriksen, senior vice president-agribusiness at IHS Markit, speaking via Zoom at a videoconference of the Kentucky Riverport Freight Summit, said, “A lot of barges have been corralled. It’s just a matter of getting them to the rightful owners in the Gulf and making sure of what cargo is in there and what condition it is in as we go forward.”

At least one shipper is trying to divert cargo to an elevator in the Pacific Northwest, and competitors are coming forward to offer shippers other alternatives because they have availability, Eriksen said. “Right now we’ve got an export elevator, there at Reserve [Louisiana], that represents roughly 8 to 12% of capacity in the Gulf, and that’s not any small volume,” Eriksen said. “That’s a very large facility that’s going to be down for a long time. And others that don’t have power. People can’t get there.”

Levees held

However, the “silver lining,” according to Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, was that the $14.5 billion hurricane risk reduction system put in place by the Corps of Engineers since Katrina has held. Called the Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction system, it is a network of levees, pumps and floodwalls designed to protect the region against “once-in-a-century” storms and floods.

In an Aug. 31 press conference, Edwards said to his knowledge not a single federal or parish levee failed, although a few were overtopped. Most of the damage from Hurricane Katrina came from floodwaters rather than the winds.

“It would be a different story altogether had any of those levee systems failed," Edwards said. “Having said that, the damage is still catastrophic, but it was primarily wind-driven.”

David Murray and Shelly Byrne can be reached at [email protected].