“The management practices that are used on those working agricultural lands are really the dominant factor in our resulting water quality.”

Andy Lyon, executive director with the Kansas Department of Agriculture-Division of Conservation, described the nearly 46 million acres in Kansas that are dedicated working lands of farms and ranches as some that must be managed properly. Without water on those lands, their production is often limited.

Lyon led the water quality session at the Governor’s Conference on the Future of Water in Kansas, Nov. 18.

One of the speakers in the session, Will Boyer, Kansas State University northeast Kansas watershed specialist, provides education and technical assistance to agricultural producers and other stakeholders in his area. Boyer uses high-resolution mapping data and GIS software to help producers find solutions to water quality concerns in confined feeding and grazing operations.

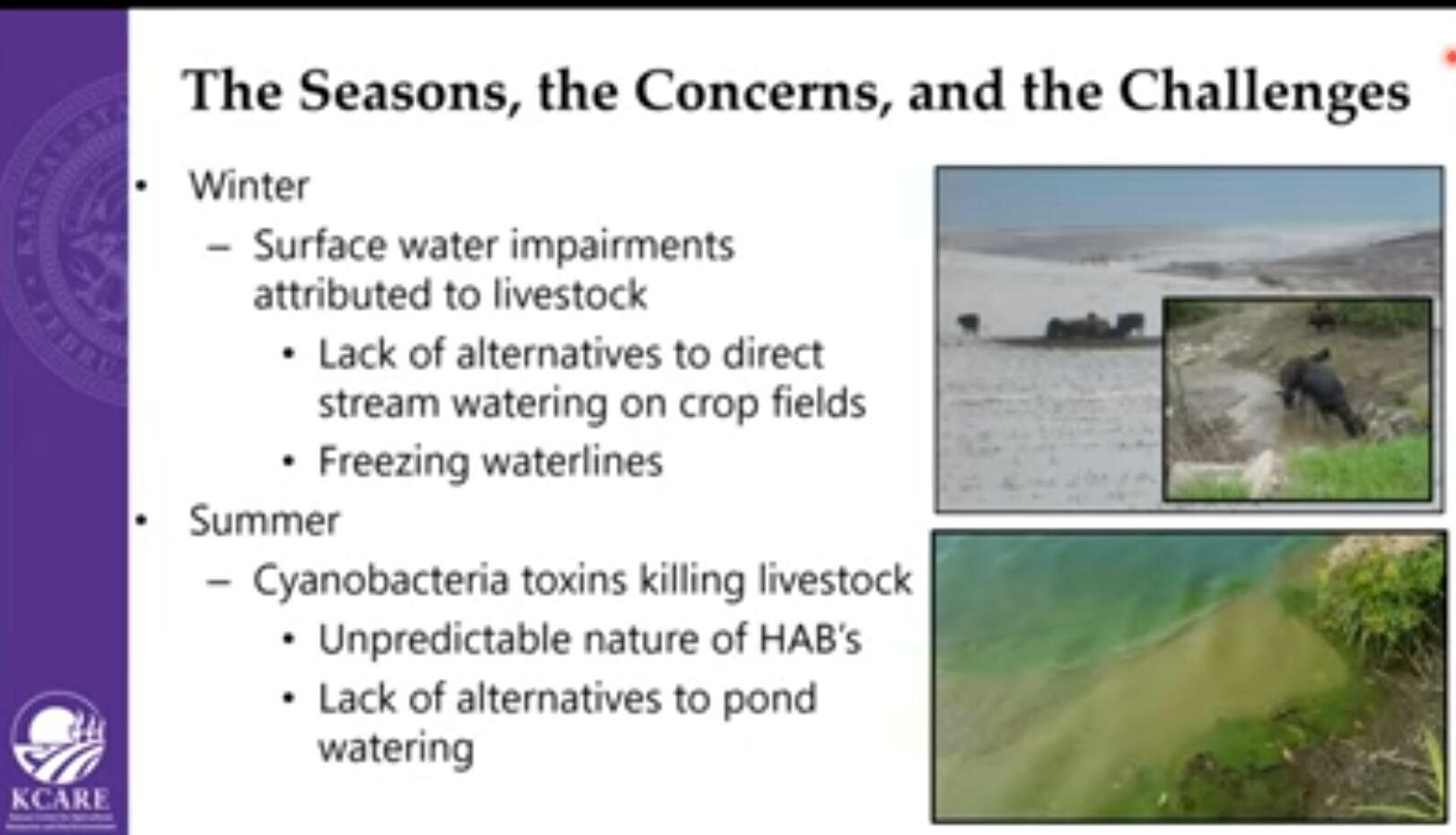

Boyer said when it comes to watering livestock it’s a tale of two seasons—one cold and one warm.

“So when it’s super cold, you got issues,” he said. “And that’s when the water quality issues related to livestock and the water quality impairment or the management of what’s going on out there is really having an impact.”

When animals are in confinement, caretakers have to bring the feed to them, and if you want to provide an alternative water supply, Boyer said, you’ve got to have a way to keep that water from freezing.

“Water is a critical, critical piece to livestock production,” he said. “It’s the most important nutrient the animals have to consume.”

The other difficult season for water is the warm months when ponds become drier and more stagnant. Flash-flood rains might bring soluble phosphorus into ponds. Even though there’s no ice to deal with warm months come with their own set of challenges.

“These harmful algae blooms are so unpredictable, it’s so hard to get your head around how they happen and what to do about them,” Boyer said. “And in terms of the best solution for a livestock producer is to just fence that pond out; don’t let the animals have access to it. But there’s so many cases where a pond is the only source of water in the pastures.”

Boyer has found that utilizing cover crops as a forage source for the animals accomplishes a couple of things.

“It helps get the cow-calf and the backgrounding operations out of the confinement pens away from the water resources and gives them a good quality forage to eat,” he said. “And most importantly, it decreases the time they’re in confinement and increases the natural distribution of the manure as opposed to letting it build up in confinement pens were eventually the producer finds time to get that out on the field with the manure spreader. So those are the big factors there.”

When trying to solve the problem of providing “liquid water” instead of a solid variety (ice) to the animals, it takes a little thought and even ingenuity. If using cover crops, producers often find the crop fields typically don’t have fence or water development. The problem could possibly be solved by just looking around—if there’s a water source or a pasture with a spring or even a well, there’s an opportunity to create a watering system with a little bit of thought.

In a gravity fed water system, Boyer said there could be a pond on the other side of a little dam with some water that flows. If part of the system is buried, the ground protects the water and if there happens to be a little sunshine on the water keeping the system from freezing—a trickling valve could help keep the water from freezing up completely.

A spring tank is an outstanding source for watering livestock in the wintertime.

“The water is warm and it keeps flowing,” he said “And you don’t have this challenge of dealing with ice.”

Next best choice when grazing on a crop field is to scout the area for an old well that could possibly be used. Maybe there’s an old farmstead with one still operational.

“The great thing about the wells is that you can set it up so when you pump the water to the tank, the water can drain back down into the well that’s in the water delivery line,” Boyer said. “And then that will keep that line from freezing.”

Another source Boyer suggests is to find a source of near the crop field or even within it. There’s a variety of options on building a pit with a pump system to get water where it’s needed from a water source that’s existing on land like a creek or pond.

Hauling water would be the last choice for Boyer.

“That’s the choice that a lot of people end up making,” he said. “And compared to how expensive a water development can be, that may be the most economical choice.”

Moving on to the summer and a different perspective of water quality because of algae blooms and the toxins associated with those. Through his research he’s found using a slow sand filter to remove the toxins can work pretty well.

“For public drinking water, the slow sand filter was really quite effective” Boyer said.

This system helped keep the bacteria or the cyanobacteria cells from getting down into the drinking water, but also helped removed the toxins in a biofilm that grows on top of the sand filter.

In Boyer’s work for this type of system they stared with food grade chemical totes with a network of PVC pipes or holes in the bottom discharge point just at the top of the sand level. There’s also a layer of gravel in this set up.

“We tweaked the design,” he said. “It had multiple sizes of gravel and multiple sizes sand particle sizes.”

Getting a producer to adopt something like these filtration systems takes a little bit of work.

“We didn’t say that it was very practical way,” he said. “I mean, getting a producer to adopt something like this needs to be fairly, fairly simple and straightforward or is it’s going to be too much of a burden for them to try to find six different types of material put in the sand filter.”

Boyer and his team limited it to different sizes, materials and fabrics available. As it is filled with sand, water has to come in at the same time to try to get the air pockets filled up and get everything completely saturated.

“We learned that just driving it down the road will help it all settle down and in the place to be ready to go to work,” Boyer said.

It’s important to make sure you keep from damaging the biofilm with the inflow from the pump.

“You’re only supposed to allow 2 inches of water on top of the biofilms,” he said. “Make sure that gets the aeration that it needs in order to do its job. So making sure that your filter was level was really important.”

At one test site a low float mechanism was used to turn the pump on and off. Boyer said you could use a siphon from a pond to a system like this.

“It would really work pretty well and cut the cost down a lot,” he said. “So that’s something that personally I consider.”

Managing the biofilm, is probably one of the biggest obstacles in getting this system running and in a maintainable system.

“One of these systems, one of the filters probably be enough to do 25 head and maybe up to 50 head if you if you manage it carefully,” Boyer said.

Boyer found water sampling was expensive for this research since they had to pump it in about seven times.

“Six times the algae level wasn’t so high and we only tested for the toxin three times,” he said. “And the toxin actually made it through the filter one time, but it was at a low level. So hopefully that wasn’t too bad of a result for our initial tests.”

He questions whether or not there wasn’t human error involved in the testing.

“Because we didn’t have our testing protocol or anything like that that we were following,” he said.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].