Wildfires are ravaging areas of the High Plains and New Mexico has been particularly hard hit. As of May 6, the Hermits Peak and Calf Canyon Fire have burned a combined 168,009 acres since the Hermits Peak fire started April 6 and Calf Canyon April 19. This fire is around 20% contained, according to inciweb.nwcg.gov.

New Mexico State University’s Cooperative Extension Service has pulled together a number of resources for residents and landowners to prepare for the event of a wildfire on their property.

Doug Cram, NMSU Cooperative Extension Service forest and fire specialist, said in a recent webinar that residents need to be aware that “we live on a fire planet, a fire continent, fire region and fire state.”

“Fire is a part of our system,” he said. “For over 100 years, we’ve been suppressing fire and excluding fire in management decisions.”

Add people into an arid environment like New Mexico, and mix in climate and some drought, it’s a recipe for wildland fire disaster.

Historically, from a farm and ranch standpoint, firefighters were able to catch wildland fires as they come out of the forests or woodlands.

“But in drought situations that is really no longer possible,” Cram said.

In rural situations, riparian areas aren’t necessarily much better off. Cram has witnessed some extreme fire danger in recent months. Forest fires tend to move differently than ones out in open grasslands.

“It’s not necessarily this wall of flames,” he said. “Rather all these red islands are a result of firebrands being blown out in front of the fire, starting little fires—they become big fires. This is the challenge of living in a wildland urban interface or in rural environments.”

Cram warns that when living out on a farm or ranch, trying to stop a wildland fire with a garden hose is not safe or effective.

“You’ll have to deal with intense heat, smoke and flames,” he said. “We have this interesting dichotomy in terms of natural disasters. Whether it’s a hurricane or tornado or mud slide, we tend to seek shelter, sort of a crawl into our shell. However, with wildfire, we seem to get on our Ninja Turtle.”

That tends to end badly, Cram said.

“Wildfires should be over here with the other natural disasters and leave the firefighting for the firefighters,” he said. “We tend to lose more individuals in grass and brush fires as opposed to forest fires.”

Short grass fires are challenging because as wind speeds go up the fire behavior gets more unpredictable and could become deadly. Cram suggested a number of tools to consider when trying to protect a farm or ranch from a wildfire.

Equipment

When parking equipment, park it away from sheds, barns or other structures. Leave enough space to mow or weed eat between them.

“Sometimes these vehicles have grass buildup around them,” he said. “If an ember lands on one vehicle, it ignites this vehicle, and can be vehicle-to-vehicle ignition. So create defensible space where equipment, fuel and chemicals are stored.”

Cram suggests storing them about 30 feet apart from each other and—graze it, mow it, spray it. You can also make a gravel pad to create a barrier for your equipment.

Sign up for HPJ Insights

Our weekly newsletter delivers the latest news straight to your inbox including breaking news, our exclusive columns and much more.

Propane tanks

According to Cram, propane tanks need to be at least 30 feet from structures and for a 10-foot radius non-combustible zone to be created. Remove trees and grass around the tanks, anything that could cause ignition.

“Certainly if the propane tank goes off it’s going to be a pretty hard, intense burning environment,” he said.

The safer the environment around the tank, the better. Pavers underneath the tanks could help keep combustibles from under the tank.

Hay stacks

Stacks of hay can be “quite a fire hazard,” Cram said, and farmers and ranchers need to create a defensible space around these stacks. They should be stored anywhere from 30 to 100 feet apart, and if possible, don’t keep all the hay in the same location.

One storage example he’s seen is where a producer stores a certain number of bales in one location, and more in another.

“So that if this hay bale, this collection goes up in the fire, then maybe this one wouldn’t,” he said. “Again, create space between haystacks.”

Same goes for hay storage structures, keep overgrowth of weeds or grass around the buildings trimmed, sprayed or put gravel over it.

Structures

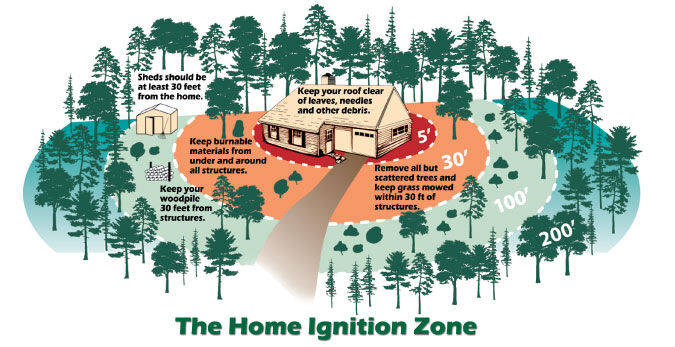

When looking at barns, sheds, or outbuildings, create a 10-foot, no-fuel zone around the building. Concrete walkways, gravel paths and bare soil also help. Same goes for metal roof and siding, and tight sealing doors and windows.

“The fuel load buildup around the structure is going to leave it pretty vulnerable,” he said.

Keep trees and shrubs away from a building, as this helps prevent the embers from landing on the structure.

“Of course in the spring you again probably want a weed-eat around it,” he said. “Maybe even create some bare ground.”

Fuel breaks

When creating and maintaining fuel breaks around pastures, homes, and buildings, keep in mind they need to be about 15-feet wide.

“Oftentimes it really depends on the wind and maybe the fuel type we’re dealing with,” he said. “The fire breaks can be effective again in some circumstances.”

The break might need to be wider if the wind is blowing faster, with flames reaching higher.

Management

Using fire to manage land can help to manage the fuel load.

“This is a unique tool that in the spring—to go burn off that fuel. They’re just waiting to rip off on a red flag warning,” he said. “So again, utilize prescribed fire, create fire breaks and reduced fuel loads.”

Grazing to reduce blazing helps target those areas that need it the most. Allowing small livestock to graze around homes and other structures that are not easily mowed can reduce fuel loads.

“Rotational grazing can be useful and consider pastures that are at greater risk of fire,” he said. “For example, near railroads and highways and open access.”

Removing the extra fuel load can help with fire mitigation when the time comes.

Evacuation plan

Cram said it’s always good to have a livestock evacuation plan. This includes ensuring proper registration of animals and brands. Have paperwork ready when needed. Always have a contingency plan for animals and humans.

When a farmer or rancher has to consider evacuating without animals, Cram said it depends on the situation whether or not the fences need to be cut or gates left open.

Sometimes it’s hard to know where the fire is because of the smoke.

“And suddenly you’re stuck there in the middle of your pasture with unburned fuel between you and the fire and the winds blowing 25 to 30 miles an hour,” he said. “It can be a dangerous situation.”

Any losses will need to be properly documented. The U.S. Department of Agriculture offers the Livestock Indemnity Program for farmers and ranchers.

“Make sure you have the adequate insurance coverage and in terms of farms and ranches,” he said. “There’s often riders you can get that will cover livestock, forage, crops, equipment and so forth.”

Cram said it can also be useful to have property maps available to fire fighters depending upon the nature of the fire. Having marked roads, gates, water tanks and keys to locks can also be handy.

“And finally, again in rural environments, you want to know multiple escape routes,” he said. “But the point is you want to ahead of time, utilize whatever means you can—maps, google earth, talking to your neighbors and find multiple evacuation strategies.”

For more information about preparation for wildfires visit https://aces.nmsu.edu/defensible_zone/resources.html.

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].