Behind all the blowing dust and horizontal snow, much is happening in western Kansas to abate effects of declining groundwater.

Efforts among food producers include using less of the resource while still posting profits.

“We’re not sitting still. Farming practices are not like they were in the ’70s and ’80s, with the belief that the water was always going to be there,” said Clay Scott, a farmer in Grant County, Kansas.

Saving water has become part of the culture as the region’s biggest hope for success is stressed through business, local government and education efforts.

Shoulder shrugs aren’t as common among big water users out west as science, innovation and stewardship are embraced from classrooms, downtowns and irrigation circles dotting the flat landscape.

More irrigated farmers are willing to fight for every drop of water through cooperation and innovation, adding life to what’s left of the precious resource.

“We’re not trying to fix it just with policy. We’re trying to fix it with action,” said Weston McCary, technology project coordinator for the Kansas Water Office.

Mindsets are changing from a half century ago, when some ignored warnings and declared the Ogallala Aquifer, stretching more than 175,000 square miles from the Dakotas to Texas, would never go dry.

“It comes down to human attitude, with producers changing their vantage point on things,” he said.

Groundwater decline

Second only to oxygen among the vital elements of life in Kansas’ highest elevations, groundwater has been steadily declining since irrigation mushroomed beginning in the late 1960s.

Sucking water out of the earth helped the semi-arid region bloom into lush prosperity, by raising more food through plants and animals, primarily beef cattle.

It’s not uncommon to find irrigation wells in western Kansas that have diminished to dust-filled holes, or pump so little they are no longer viable.

Other wells remain vibrant in the farm-and-ranch economy, and folks want to keep it that way.

Declines have been evident for decades, with reductions in the saturated thickness of the underground supply exacerbated during years with little rain.

Measuring depth

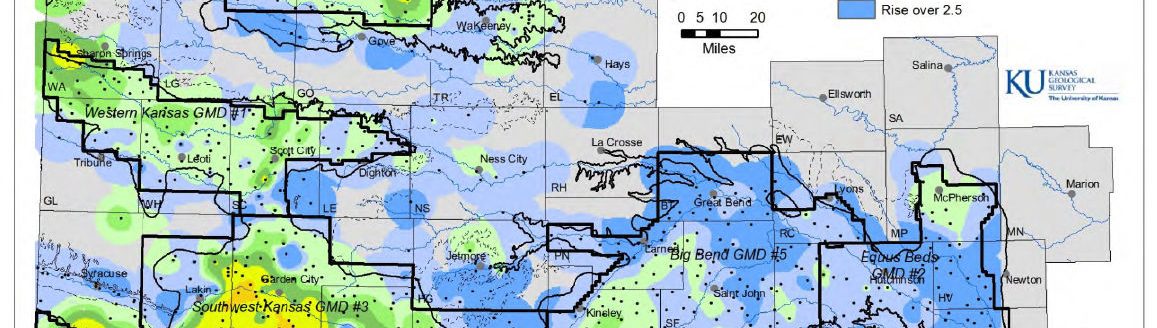

The Kansas Geological Survey has been measuring wells every winter for decades, with the help of the state’s agriculture department, and are mapping a general decline.

Water levels can vary greatly, said Brownie Wilson, KGS water data manager, pointing to 2011-2012 when average annual declines were from six to 12 feet.

“Southwest Kansas pumped half of the groundwater used in the state during the drought year of 2011, when the decline was four and a half feet,” said Mark Rude, executive director of Groundwater Management District No. 3. The GMD covers all or parts of 12 counties in southwest Kansas.

“(Annual declines) were less than a foot for several years after, for two reasons—agricultural adaptation, and two, it rained,” he said.

Results from this year’s annual measurements of 1,400 wells were also far less drastic, Wilson said, with an overall average decline of less than a foot.

“Some areas are pretty close to zero. Other areas have higher declines than others,” he said. “Typically, the bigger declines are in southwest Kansas, in some of the most arid parts of the state.”

Solutions are simple: rely on recharge coming from the surface, reduce pumping by changing farming practices and implementing new technologies. Praying for rain an important strategy for many growers, too.

“The big driver there is precipitation. That’s especially true of the Ogallala side of the High Plains Aquifer in Kansas,” Wilson said.

Rain and snow “impact pumping demands,” he said, “and pumping, in turn, influences aquifer conditions. Some people think there are underground rivers flowing from the mountains in Colorado to Kansas. This is completely false.”

From 2017 through 2019, “the entire state had been pretty wet when they were at or above normal precipitation,” Wilson said. “Now we’ve stepped back to drought conditions that we saw in 2011 and 2012.”

Management perspective

Not all depends on Mother Nature. There are a number of human remedies at play throughout the western one-third of Kansas, so conservation doesn’t hurt the regional and state economies.

Fixes so far vary between northwest and southwest Kansas. One star up north is the Sheridan No. 6 Local Enhanced Management Area in GMD 4, where irrigators voluntarily agreed to restrictions monitored by the Kansas Division of Water Resources over five-year contracts, beginning in 2013. That same community—in western Sheridan County and one tiny pocket in eastern Thomas County—renewed in 2018 through this year, and just agreed to a third term.

“It’s probably the greatest success story of the Ogallala that we have to date,” Wilson said. “We saw a reduction in decline. You can see a definite shift in water use patterns, before and after the LEMA went into effect. They’re using less.”

Water still is on a decline in the Sheridan 6 community, he said, but it’s not as drastic.

“What they’re basically doing is kicking that can down the road. They haven’t stabilized water levels, but they’re not the bullseye of the county in terms of declines, which they were historically,” Wilson said. “They’re definitely extending the lifetime of the aquifer.”

And the farming operations are still profitable, according to a 2017 Kansas State University study by economists Bill Golden and John Leatherman.

Sheridan 6 reduced total groundwater use by 23.1%, average groundwater us per acre by 16%, reduced crop acres by 10.9%, while upping grain sorghum acres by 335.4% and irrigated wheat acres by 60.3%.

“… given the certainty of groundwater use reductions, producers are able to implement strategies to maintain returns and apply less groundwater,” the report reads. “This suggests that producers within the Sheridan 6 LEMA believe they can mitigate any negative economic consequences associated with reduced groundwater use and that the benefits of groundwater conservation outweigh the costs.”

In a short phone conversation during mid-March, Golden, a natural resource economist, said the same conclusions have persisted through several years.

“I think the LEMAs are a good way to go,” he said. “It puts control of the water use in the producers’ hands. I would like to see more adoption of LEMAs in western Kansas.

“Bottom line, we can reduce water use, stabilize the aquifer and approach no draw-down.”

Not all LEMAs created the same

Earl Lewis, chief engineer of the Kansas Division of Water Resources, echoes that sentiment regarding GMD 4 in much of northwest Kansas. The district includes all of Sherman, Thomas and Sheridan counties, and parts of seven others.

“They’ve been leaders in water conservation and putting programs in place,” he said

Early data from GMD 1 a LEMA in Wichita County “is suggesting the same results,” said Wilson. “You can see a shift in the behavior of water usage.”

There are efforts to form a LEMA in Lane, Scott, Greeley and Wallace counties.

GMD 3 continues to pursue LEMAs and other water saving activities, Rude said.

What makes LEMAs work are their grassroots nature and common goals, Wilson said, with only oversight from the state level.

“You don’t want it to come down from the top,” he said.

But they don’t work everywhere. One requirement, he has learned, is that producers need to be dealing with similar conditions.

Case in point is a community north and west of Garden City, in a “ditch service area,” Wilson said.

Rude calls it the Kearny-Finney LEMA discussion area.

“They had people pumping 100 gallons a minute and others pumping 1,000 gallons a minute,” Wilson said. “There was a lot of diversity in a small area. How do you treat everybody fairly?”

Farmer-members of the working group that was formed, attended meetings and participated in surveys, Rude said.

“We went through all kinds of scenarios. The center of the conversation in a community discussion was ‘How do you do it?’ It’s not whether it’s needed to do a good thing,” he said. “It’s ‘whose ox gets gored?’ How do you do it fairly? The LEMA corrective controls have not happened yet.”

GMD 3 has notched successes in other areas.

Technology’s assistance

Clay Scott, in Grant County, used a Conservation Innovation Grant through the federal Natural Resources Conservation Service, to install and test mobile drip drag lines on the first couple of towers in center pivot irrigations systems, Rude said, for precise water application.

McCary heads the Technology Farm Program for the state. The field office is in Garden City, but he’s based in Colby.

“The goal is to foster adoption of practices, equipment and technology that result in significant water conservation, and getting knowledge, practices and equipment into producers’ hands,” McCary said.

Soil conservation with nutrient retention is also high on his list. But generally, McCary said, “it’s the entire gamut of getting an ideal package that is appropriate for each producer’s field.”

His cocktail of approaches includes soil moisture probes, high-tech soil mapping, using cover crops, and knowing when to stress crops such as corn.

“When they put down more roots, you don’t have to keep the upper levels of soil constantly saturated,” McCary said. “That promotes better water quality as well, so we don’t have the leaching of nutrients into the watershed.”

In six years, 14 flagship Water Technology Farms have been established with producers in western Kansas, he said, and there are projects on 10 other producers’ fields.

“We’re learning to select great hybrids that are drought tolerant, but still perform,” McCary said.

Same goes with controlling irrigation from a smartphone.

“It’s like fuel injection,” he said. “I don’t know anybody who would want to go back to a carburetor that vapor locks on a hot summer day.”

Conservation paramount

There’s no doubt mistakes were made 50 years ago, but “not everybody was headed down the wrong track,” said Lee Reeve, a farmer and rancher in southern Finney County, Kansas.

“The whole bottom line is the more we can be frugal with the water, the longer it’s gonna last,” he said. “We’d love to get to a place where you’re sustainable, getting about the same recharge from rain, and get (declines) slowed down to the point where we have a lot of life ahead of us.”

Saving water is getting easier, Reeve said, estimating it takes 25% to 30% fewer gallons to produce field crops.

“We can raise corn with one helluva lot less water than we used to, and the technology gets better and better,” he said.

But Reeve said consumption is more consistent in feedyards, dairies and municipalities.

“People use about the same amount. Cattle drink about the same amount, so it’s hard to cut back there,” he said.

Some innovative crops have risen to prominence, such as triticale, a cross between wheat and rye that grows in the fall and spring and uses less than half the water as corn.

“It’s a high-quality forage crop that is very widely used. More and more of it is planted all the time and is fed as forage,” Reeve said.

New corn varieties can be raised without irrigation, he said. Back in the moist mid-1990s, dryland corn snared headlines in Scott County when it yielded 150 bushels to the acre.

“Now these guys can raise that kind of dryland with almost normal rainfall, and if the rains are timely, you’ll get over 200 bushels of dryland corn occasionally,” Reeve said. “What used to be kind of once in a decade is fairly routine now, mainly because of technology.”

Dealing with Mother Nature

But the weather out west still can be downright uncooperative.

Scott harkened back to the 2011-2012 drought.

“Phones were ringing off their hooks from farmers concerned about how dry it was, how much they pumped trying to save the wheat. The worst thing in the world is to pump the water and run out of allocation, then see the crop fail,” he said. “Now we’re in the ’22 drought and we’ve gone through 230 days without a rain of more than quarter of an inch in Stanton County. We’re bone dry, but people have adapted. We’re not pushing irrigation limits like we were.”

Part of the problem, Scott said, was a lack of stream flow in the Cimarron and Arkansas rivers, the latter that carried several thousands of acre feet of water past Dodge City every year.

“We lost that from the (1949 Ark River) compact,” he said, adding that it reduced river flows through Kansas, because the compact entitled Kansas only enough for the ditch companies to divert water from the Arkansas River most years.

Even before the compact, southwest Kansas irrigators worked out an agreement with Colorado water uses—one-sixth of all flows to Kansas and five-sixths to Colorado—according to a 1943 Colorado v. Kansas court case.

Ultimately, after more negotiation, the compact agreement split became 60-40 in favor of Colorado for only the conservation inflows to John Martin Reservoir, near Los Animas, 60 miles upstream from the Kansas-Colorado line.

“The compact recognized those (ditch) water rights, and that was it. We’ve lost a source of recharge,” Scott said. “If we could get back to even a fraction of historical flows on the Ark River, it would help bring the system into a pretty good balance.”

Wilson of KGS agrees that consistent streamflow in those rivers would improve the groundwater situation, but the vast majority of recharge would be limited to the stream channels and adjacent areas.

“It would not be enough to stabilize water levels across all of southwest Kansas,” he said.

With less water, Scott said, farmers’ mindsets changed to providing crops “supplemental irrigation,” rather than trying to fully irrigate throughout the growing season.

“Producers are backing off on (seed) populations, planting more flexible hybrids, more acres of cotton and milo,” he said. “If rains return in time, we’ll still grow a good crop.”

Saturated thickness of the aquifer under Grant County dropped approximately 2.5 feet, Scott said, compared to a decline of more than twice that much in 2011-12.

“It was partly because of efficiencies and part technology,” Scott said. “Even though the total volume of water pumped is less, with innovation and a little bit of luck from rain, we’re still seeing some of the largest grain harvests ever in southwest Kansas.”

Drag lines and “bubble irrigation,” that releases water just inches above ground to curb evaporation, are examples.

“The amount of water we’re able to put on these crops and still grow good yields, is game changing with water-saving hybrids,” he said. “That stretches across the line, from cotton to corn.”

Now age 50, Scott has two sons home from college, also eyeing careers growing food.

“I want them to have the same opportunity to farm as I did when I started,” he said.

Doing that requires tracking all needs and gallons of water used, Scott said, while constantly searching for ways to save.

“It takes profits to pay for upgrades and implement conservation practices,” he said. “We need to improve and do a better job of extending this aquifer, while knowing the value of that resource, today and into the future.

“I wish my grandpa (Merle Scott died in the late 1990s) could see what we’re doing now,” Clay Scott said. “He’d be in awe.”

Tim Unruh can be reached [email protected].