MU Extension studies loneliness in rural areas

Montana State University is partnering with University of Missouri Extension and the MU Department of Psychological Sciences to research the connection between loneliness and mental health in agricultural workers and rural residents.

The study will increase understanding of how isolation contributes to the mental health crisis in rural communities, with the goal of providing insights into targeting future interventions.

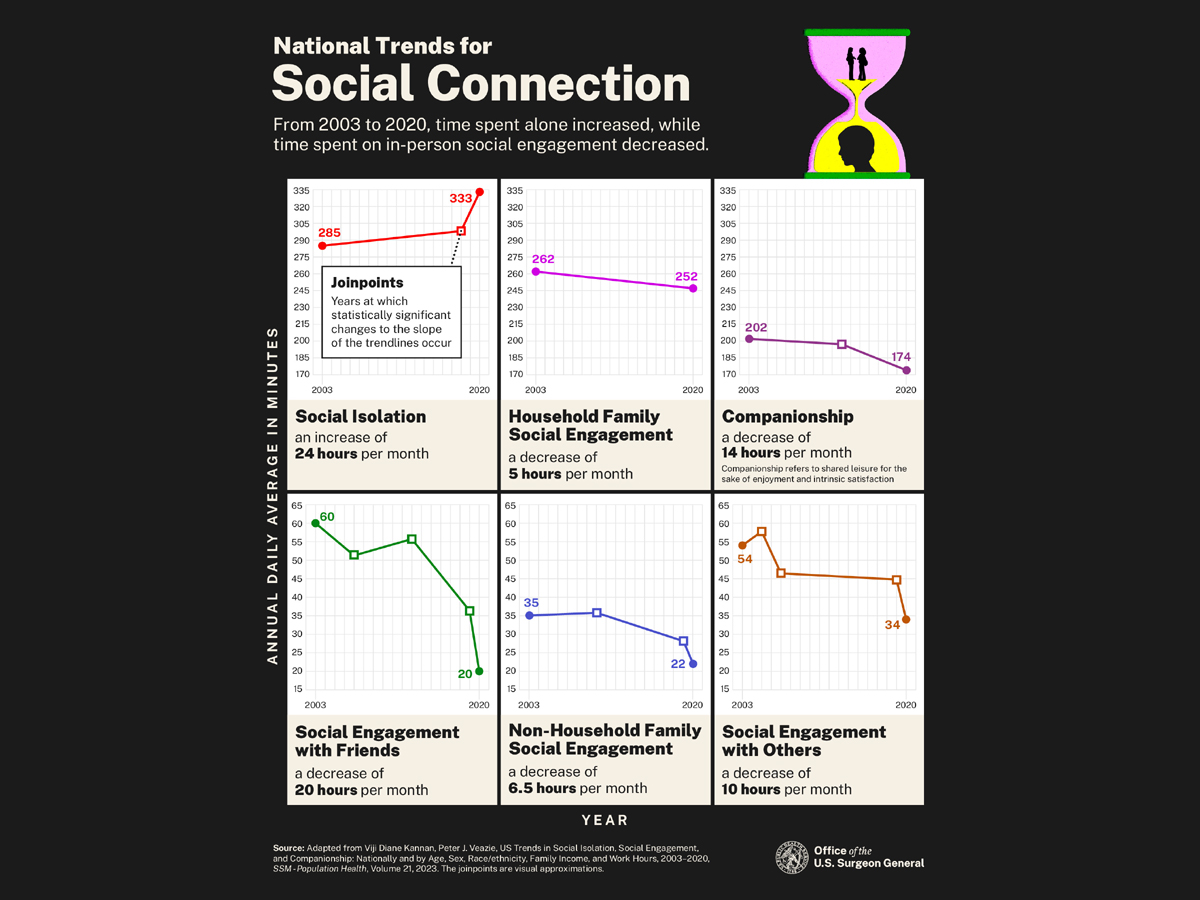

A 2023 U.S. Surgeon General advisory, “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” documents a historic decline in social connection, with Americans spending 24 more hours per month alone than they did in 2003. The report notes that lack of social connection “is as dangerous as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.”

MU Extension health and safety specialist Karen Funkenbusch says loneliness leads to poor mental health and increased suicide rates. The problem is particularly acute in rural areas. According to “Growing Stress on the Farm(opens in new window),” a 2020 report co-authored by Funkenbusch, the suicide rate among rural Missourians grew by 78% between 2003 and 2017. Over the last decade, hospital emergency department visits for suicide attempts or suicidal ideation increased 177%. Suicide rates in rural areas are 18% higher than in nonrural areas.

People with fewer social connections also see disproportionate increases in chronic disease and other physical health issues. “There is a direct link between longevity and social connect,” says Funkenbusch.

Leading the two-year research project are Peter Helm, who did postdoctoral work at MU and is now an assistant professor at Montana State, and Jamie Arndt, MU professor of psychological sciences.

Physical isolation brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic has decreased social connections, Helm says. Young people turned to digital connections to stay in touch, but this can increase loneliness since online interactions are not as satisfying as face-to-face contacts, he says.

Loneliness is not the same for everyone, Helm says. You can feel alone because you don’t sense that you belong, you don’t have a significant other or close friends in your life, or you think that other people don’t understand the way you see things. Determining how one feels and experiences loneliness helps researchers determine the best ways to cope.

The National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities provides funding for the project.

For more information, contact Megan Edwards at 660-620-8930 or [email protected].