Agricultural producers in the Republican River basin in northeast Colorado are facing the shutoff of their groundwater irrigation by the end of 2029 if they do not retire 25,000 acres of irrigated farmland in the southern portion of the basin.

Of those, 10,000 acres must be retired by the end of this year, but voluntary retirements under two buyout programs are well on track. The above irrigation photo is courtesy of u_cq5hour74s, Pixabay.

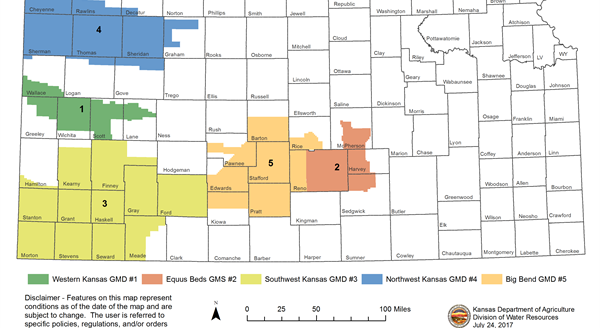

The acreage retirements are what the state of Colorado must do to abide by a resolution approved by the Republican River Compact Administration in 2016. Over several decades, Colorado, Kansas and Nebraska have negotiated the terms of the Republican River Compact that were originally established on Dec. 31, 1943, to allocate the river’s waters.

If the state of Colorado and the Republican River Water Conservation District do not meet the acreage retirement set by the resolution within the timeframe, producers owning more than 500,000 acres of irrigated farmland could face a mandatory shutdown of their groundwater wells. The compact allocates 49% of the river’s water to Nebraska, 40% to Kansas and 11% to Colorado.

Earl Lewis, chief engineer of Kansas’ Division of Water Resources, said that meeting the 10,000-acre retirement deadline by the end of this year won’t be easy. “Getting that last little bit will be the hardest part,” he said.

According to Deb Daniel, the RRWCD is working hard to meet the acreage retirement goals. Daniel has spent a lifetime in water management and has served as general manager of the Republican River Water Conservation District since July 1, 2011. The RRWCD was created by the state’s legislature in 2004, to help Colorado comply with the compact. She lives near the region affected by the retirements in Kit Carson and Yuma counties.

The Republican River in Colorado is in a closed basin that does not benefit from mountain runoff water and averages 15 inches of rainfall a year. According to Daniel, about 12,000 acres are already retired, and she expects an additional 2,000 to 3,000 acres to be retired by the end of May.

The retirements are being aided by a $30 million grant from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, all of which will be either spent or encumbered by August 2024, Daniel said. Landowners can choose between two types of conservation programs that require the permanent retirement of irrigation. If they choose the federal Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, which requires ceasing all agricultural activity on the land through the 15-year term of the contract, they currently get a higher total payment—up to $5,450 per acre.

Under the Environmental Quality Incentive Program, landowners give up irrigation and permanently shut off their wells but can still use the land for grazing or dryland farming. Currently EQIP payments, up to a total of $4,450 per acre, are paid over the five-year contract. Under either buyout regime, landowners retain all other rights.

Daniel said a “good percentage” of the irrigated landowners in the basin are absentee landlords renting to tenant farmers. Irrigation fees have recently gone up. The RRWCD fees charge for irrigated acres rather than acre-feet pumped. In 2022, the water use fee of an irrigated acre in the basin doubled from $14.50 to $30 an acre, which comes out to $3,900 a year to irrigate a 130-acre center pivot circle. Daniel said Colorado was No. 1 in irrigated acre retirements through the EQIP program in 2023, with most of these retired irrigated acres in the Republican River basin.

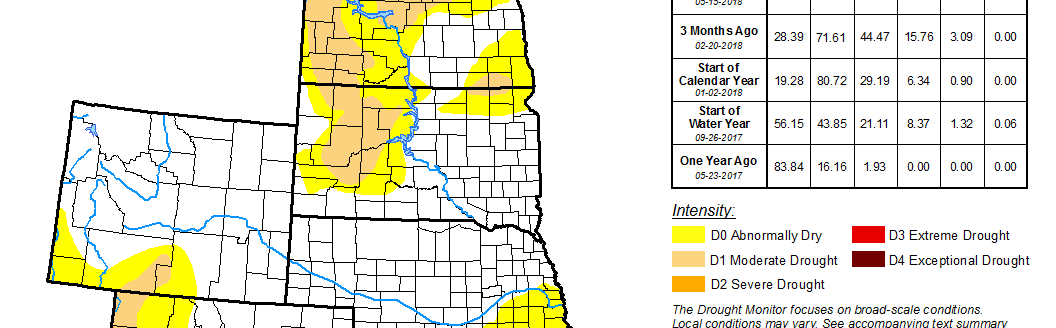

The water issues are long-standing. The introduction of centrifugal pumps along the Republican River basin during the 1950s and 1960s lowered the groundwater table in each of the states. The crisis led water users to better understand the connection between surface water, river levels and underground aquifers. In 1969, Colorado passed the Groundwater Act, a law that integrated surface and groundwater rights under the term “conjunctive use.”

Lewis said the compact remains a good framework for coordinating water allocation in the basin. “We see this as a good compromise, collaborative approach. It may not be perfect for everyone, but it was thought to be fair at the time. The states have worked well together.”

Buyout precedents

Farmland all over the West is facing similar issues. In 2005, the Idaho Water Resource Board bought the rights to 98,826 acre-feet of water rights from the Bell Rapids Mutual Irrigation Co., which had managed irrigation of 25,000 acres of desert since 1971, making potato and beet farming possible. The issues triggering that buyout included the increasing cost of electricity to pull water from the river and the state’s need to conserve river habitat for endangered steelhead salmon.

More recently, the Westland Water District in California—covering a tract of land about the size of Rhode Island—bought out the water rights on 20,000 acres, triggering a court battle that ended when the California Supreme Court agreed with lower courts in denying a contract issued by the water district in 2020, saying it overstepped its authority.

David Murray can be reached at [email protected].