When it comes to beef genetics, Gardiner Angus Ranch has a legacy of persistence.

The late Henry Gardiner believed that outside the box thinking was critical for not only delivering top quality cattle, but also adding value to them.

The Gardiner family carries on the tradition. Today, the ranch is home to more than 4,500 registered and commercial females. GAR markets approximately 2,600 Angus bulls each year. More than 125 elite bulls are serving or have served in artificial insemination bull studs. The ranch purchases more than 5,000 head of steers and heifers from GAR customers, retains ownership and markets through U.S. Premium Beef. The guiding philosophy driving every decision is to add value to every animal throughout the production system, ultimately producing Prime beef. If the ranch successful, its customers have the same opportunity to be successful and profitable.

The ranch includes 48,000 acres in southern Clark County, Kansas, along the Oklahoma border. The state-of-the-art Henry and Nan Gardiner Marketing Center includes an educational center and arena where buyers can see what they are buying.

Success is tied to a timeless philosophy, said Mark Gardiner (pictured above), who along with his brother Greg and other family members oversee the operation.

“We’re in the genetics business, and the Golden Rule is our guidepost. Our goal is to produce cattle that enable our customers to make money. If a customer has a concern, we take care of it.”

Gardiner Angus Ranch implemented artificial insemination 60 years ago. Mark remembered his dad, a Kansas State University graduate, being involved in the pioneering days at K-State. In 1964, Henry made the decision to use only A.I. to breed cows. Since then, 100% of the bulls and females born on Gardiner Angus Ranch are the result of A.I. and embryo transfer.

Meticulous records

Long before computers and the technology we have today, Henry Gardiner was committed to improving the efficiency of the cattle and quality of beef. He kept meticulous records on a ledger pad and clipboard, year after year.

From 1964-80, the average weaning weight of calves was 523 pounds. Knowing the dairy industry had made progress, Henry was certain similar results could be made in beef cattle.

Mark said that today Angus is the “breed of choice,” as measured by more than 80% of beef cattle in the U.S. having Angus influence, but that wasn’t always the story. Henry recognized a perception that the Angus breed was considered short and squatty and not enough frame in comparison to other continental breeds from Europe.

However, Henry knew Angus’ maternal instincts, calving ease and milk production to nourish young calves was equally important. Mark said his dad believed, with genetics, he and other breeders could make a difference. His first task was to give each animal a job description.

Henry worked with the American Angus Association, gathering data for structured sire evaluation all through the 1970s. In 1980, the association printed the very first “field data report,” which took ALL of the widely used bulls of the Angus breed and compared them for the traits of economic merit. This had never been done before. After analyzing the report, Henry realized that the bulls he had used from 1964 to 1980 were average for these traits. This made sense to him because he had documented no change for weight in the calf crop during this period. He knew when he saw the report, the information was accurate, and the only way to make progress was to use progeny proven sires for the traits of merit. This is what he did, and it worked!

Mark remembers conversations he had with his dad when he and his brother were college students at K-State. They began selecting for the traits of economic importance to increase the weaning weights. By 1988, weaning weights increased to 800 pounds. Weaning weights have continued to increase. Although environmental challenges such as drought and adverse weather conditions affect weights, the 2024 average weaning weight of all male calves was 885 pounds.

“Henry believed we could use modern technology and selection tools to design and identify the ‘Michael Jordans,’ ” Mark said as a reference to genetic outliers and comparing to what many basketball fans believe is one of the greatest players of all time.

“Selecting for traits like calving ease and efficient early growth were measurable,” Mark said. Objective traits that were measurable became the benchmark, and today the Gardiners are taking it farther with genomics.

“Today, with genomics, it makes a difference. We can identify bulls at an earlier age,” he said.

The connection to markets

As the Gardiners looked ahead, Henry and his sons believed that producing high quality beef cattle was important, and so was adding value and being rewarded. While the Gardiners were hitting important production benchmarks, Mark said there was a missing link. They were not being rewarded for higher quality beef.

Consumers were willing to pay a premium for Choice and Prime cuts, he said.

Even as industry reports and audits noted the opportunity as early as 1990, change didn’t happen overnight. Mark credited the vision and commitment of the American Angus Association’s launch of Certified Angus Beef, which began its program in 1978, to help ranchers to link their product to profits. In 2024, the program sold 1.2 billion pounds of Certified Angus Beef brand across the U.S. and 55 countries.

All beef producers were still struggling to identify high-valued cattle and market the cattle in a system that incentivized quality through added premiums. The Gardiners and other cattle producers who had a shared interest in connecting beef production to consumers invested $80 million in U.S. Premium Beef, Kansas City, Missouri, in 1997. U.S. Premium Beef formed a partnership with Farmland Industries and purchased half of Farmland National Beef Packing Company, which at the time was the nation’s fourth largest beef processing company.

The partnership required U.S.P.B. to deliver 735,000 head of cattle each year. The cattle were sold on a value-based grid, negotiated directly with the company’s new industry partner, National Beef. The cattle are processed in Kansas at plants in Dodge City and Liberal.

Mark remembered those early days when he and other cattle producers had to not only deliver cattle but also build demand. Then a producer could earn a 35 cents a pound premium for a Prime carcass.

“We were really excited and pleased,” Mark said, adding that incentives added a value that can be traced back to the genetics of the animal. “I became a better breeder when I became an owner of U.S. Premium Beef.”

It taught him the importance of marbling, which helps add flavor, tenderness and product consistency to beef. With the use of genetics, he can raise an animal that meets and exceeds the quality, value and affordability signals sent down the supply chain. Having an economic incentive pays, too. If a 1,000-pound carcass can generate $350 in added value, then producers have a financial incentive to replicate that product.

“We are the protein of choice,” Mark said. “Beef is the choice for celebrations.”

Recognizing that quality can be monetized is important, he said, and even during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, consumers still wanted beef in their diets. Listening to what consumers want is the key, he said. Producers can use genetics to raise cattle to meet consumer demands.

Cattle’s success

The success of the cattle industry is one that he enjoys telling because the ruminant animal can consume (cellulose) plants, put on weight and thrive on rangeland not suitable for cultivated crops. That story resonates with consumers.

The industry is not without its share of challenges. The nation’s cowherd, at an estimated 28 million head, is one of the smallest since 1950. Mark Gardiner said progressive producers are going to continue to apply genomics to drive efficiency while the herd slowly expands.

The need for protein is necessary to feed the world, he said. Today’s population is about 7.8 billion people, and there are estimates it could reach 10 billion people by 2050.

Over the next 25 years, farmers and ranchers will continue to be tasked with producing a reliable and safe food supply. “We’ll do it with technology and innovation, and we’ll make it better,” he said. “That’s the American way.”

Gardiner also encourages producers to stay optimistic. The Gardiners have dealt with long-term droughts and wildfires, as examples, but they have stayed with a business plan. The beef story is unique and diverse, Mark said.

Sage advice

Mark believes that alliances and collaboration can help ranchers build their own plan and reduce risk inherent in the cattle industry.

He remembers his dad telling the next generation to be wary of debt, so watching expenses remains a hallmark for the operation and is wisdom he shares with young ranchers.

Henry and Nan Gardiner and family had to weather the 1980s. Mark and Greg Gardiner still remember the difficult times many producers experienced when interest rates on operating loans reached 18%. Mark remembered his dad saying how important it was then to avoid borrowing money. “Henry would tell us that a successful family operation was about work right, not birthright.”

Gardiner Angus Ranch, including family, employs 10 full-time workers and four to eight interns each year. Today the family continues to honor Henry and Nan through the Henry Gardiner Scholarship and Lecture Series at K-State University. To date, $250,500 in scholarships have been awarded to 54 students majoring in Animal Science & Industry or a closely related field. Mark said giving back benefits the beef industry as he enjoys visiting with students who benefit from the latest in research and practices.

“I want to learn from them, too,” he said.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].

Tidbits

The Henry and Nan Gardiner Marketing Center carries a quote from Henry Gardiner, who died in 2015. It says, “To be successful, we must have a dependable product that is consistent from one time to another, from one consumer to another, and is consistently good.”

Henry Gardiner’s roots in Clark County, Kansas, included his grandparents beginning in 1885, and he admired his parents and their ancestors’ persistence. They persevered through crop failures and the Great Depression.

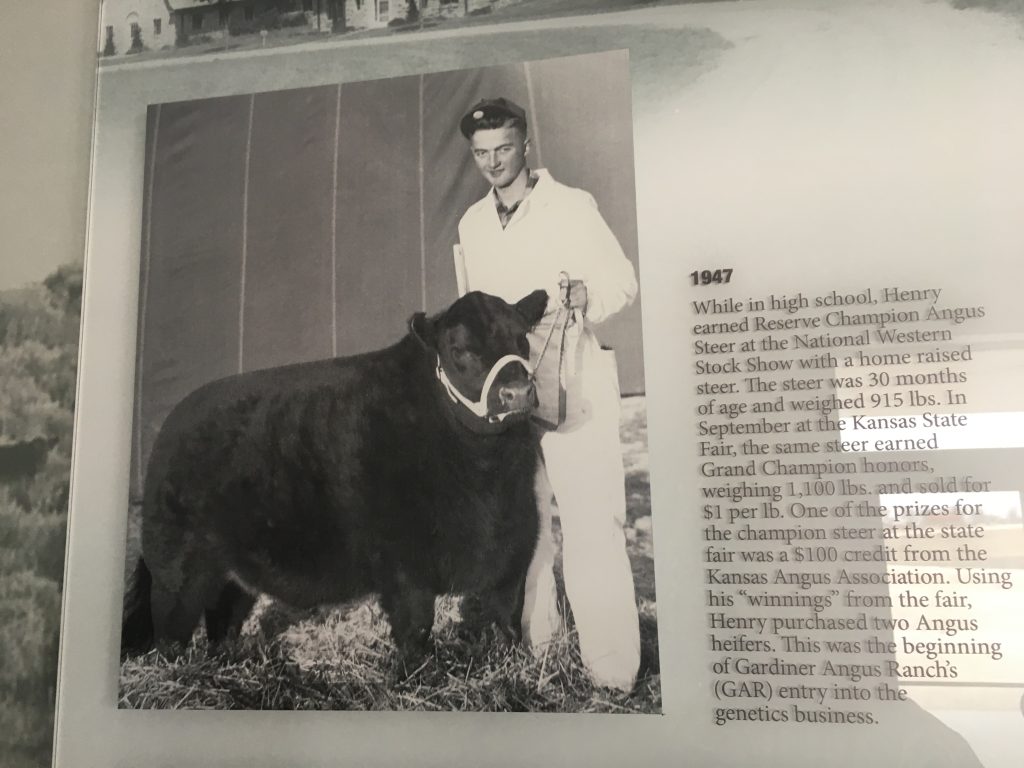

In 1947, while in high school, Henry earned reserve champion Angus steer at the National Western Stock Show with a home-raised steer. The steer was 30 months old and weighed 915 pounds. In September, at the Kansas State Fair, the same steer earned grand champion honors, weighing 1,100 pounds, and it sold for $1 per pound.

One of the prizes for the champion steer at the state fair was a $100 credit from the Kansas Angus Association. Using his winnings from the fair, Henry purchased two Angus heifers, and that was the beginning of the Gardiner Angus Ranch’s entry into the genetics business. Henry went on to graduate from Kansas State University with a degree in animal science.