Trial and error has led Macauley Kincaid down a path that has worked best for his farm. Kincaid was recently awarded the Soil Health U and Trade Show Regenerative Producer of the Year by High Plains Journal.

The 26-year-old Jasper, Missouri, farmer began working on the family farm with his grandfather and uncle starting when he was 14. But the death of his father when he was 20 helped him to see where his involvement with the farm and what practices he had been using were going.

“This is more of a personal answer—my father—he died of cancer,” Kincaid said. “You hear all these things from the media or wherever and it’s farmers are causing these issues and problems, so I just kind of looked in the mirror and thought about what I was doing on my farm.”

What he saw in the mirror was how his entire farm revolved around something he wasn’t sure that he wanted.

“So I just kind of changed my outlook on life. Instead of farming with death, I try to farm with life,” Kincaid said. “It’s kind of one of the big drivers—the reason I changed and then, of course, financial stability.”

When Kincaid was 18, he started renting ground and building back his farm from there. But those first two years he just couldn’t make it work with conventional practices.

“It wasn’t paying and I lost my first rented farm,” he said. “I thought, well if I want to farm I’m going to change some my practices.”

The burden was eased some when he inherited 60 acres of row crop ground that was paid off, but he still wanted to find a way to make money farming.

“I just kept going and I was doing some research about cover crops and no-till and I knew I wanted to be a no-till farmer, but I couldn’t make the no-till yield very well,” Kincaid said.

He struggled with wet ground at planting time, other problems, as well as his crop rotation.

“I started following guys like Gabe Brown and Ray Archuleta. I met Michael Thompson and I started talking to these guys,” Kincaid said. “And they just kind of set a seed so I just went all in.”

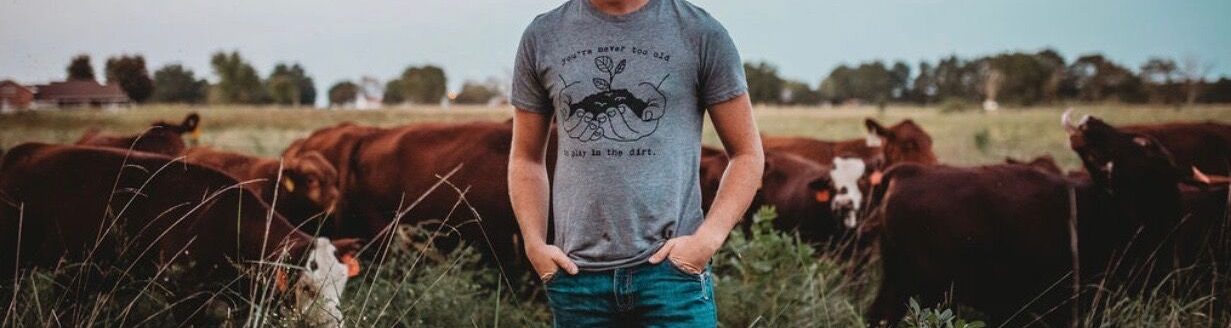

Now, he primarily raises corn, soybeans, barley, wheat, oats and a number of cover crops for seed.

“What I do is I spread my rotation out to three or four years on most my cropland,” he said. “In between all my cash crops I always have a cover crop growing,” Kincaid said.

And now most of his row crop fields are fenced and have water for his 80 cow-calf pairs and custom grazing business.

By his third year of farming he had 100% cover crops, was no-tilling and began integrating animals on the row crop ground. He credits those connections made with soil health experts with getting him where he needed to be. Plus he’s tried to take control of how much he’s spending on the farm.

“I’ve really worked with that philosophy,” he said. “I do have some goals every year and they do change. One of my goals for next year is I want to raise 100 bushel milo, and this year I tried milo for the first time and I didn’t do very well with it.”

Those who know Kincaid know just how passionate he’s become about soil health.

“If anybody knows me very personally that’s all I pretty much talk about, and I’m an avid student,” he said. “I’m always trying to learn new things, trying different things, and pushing to succeed.”

One thing that’s important to him when applying a cover crop is letting the biomass accumulate to increase the soil health, especially on row crop ground. But someone wanting to improve his soil health should reach out to those with knowledge.

“Anybody that wants to get started in this, I think they should reach out, try to grab mentors—I think that’s really important,” Kincaid said. “Try to find someone they can look up to. They don’t have to be from your area, but just have someone that can help you and work with them.”

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected]