Food grains show steadiness amid COVID-19 commodity troubles

Texas wheat producers could see an opportunity as food grains show steadiness amid calamity for other commodities, said a Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service economist.

Mark Welch, Ph.D, AgriLife Extension economist, College Station, said food grains have avoided much of the “complete wreck” market disruptions have made of commodities like corn, cotton, beef and crude oil. As dairy operators dump milk and oil markets report negative-sum prices, prices for wheat and rice remain relatively steady and have experienced brief gains during the COVID-19 crisis.

Texas wheat growers could see marketing opportunities amid steady prices for food grains.

Cattle, corn and crude oil prices were all down at least 20% compared to wheat and rice, which were down around 3% to 4%, Welch said.

“So many commodities are cloudy amid this crisis, but wheat and other food grains have held up,” he said. “I think it’s because COVID-19 has created underlying demand for these food grains as countries around the globe take an extended view of their food supplies.”

Welch said nations like Russia and Ukraine have already announced the possibility of limiting exports to make sure their people are fed. The pandemic timeline and overall growing conditions in those countries and other major wheat-growing nations going forward will weigh heavily on those decisions.

Weather in the U.S. this spring could also affect domestic decisions, Welch said. Freezes in Texas and Oklahoma damaged wheat destined for grain production, but it remains unclear if it will hurt overall yields.

AgriLife Extension agronomists estimated Texas grain-wheat acres could see up to a 10% yield loss based on reports in the state’s wheat growing regions. It’s also unclear how many Texas wheat acres were going to grain.

Wheat grazing or grain?

Many beef cattle producers graze winter wheat to pack pounds on winter calves. Most pull their herds off the wheat by mid-March to produce grain in mid-summer, however in recent years, cattle prices were steady enough amid poor grain prices to entice many producers to graze out rather than go to grain.

But this year, Welch said, falling cattle prices and steady prices for food grains might mean a higher number of producers could go to grain.

The decision window has been tricky this year because of COVID-19. The timing of falling cattle prices and wheat’s steadiness occurred around the extreme cutoff date for producers to pull cattle to produce grain, typically March 15, Welch said.

On March 16, wheat grain prices were $4.31 per bushel compared to $5.01 on Jan. 2, Welch said. But by March 25, grain prices gained 70 cents to end at $5.04 per bushel.

“It’ll be interesting to see what decision producers made based on the timing,” he said. “It looks like there might be some opportunity for Texas producers who made the decision to go to grain.”

Welch said there were other “pockets of concern,” such as drying conditions in parts of Kansas and the availability of workers at harvest. Grain harvests are highly mechanized, but they still require additional workers.

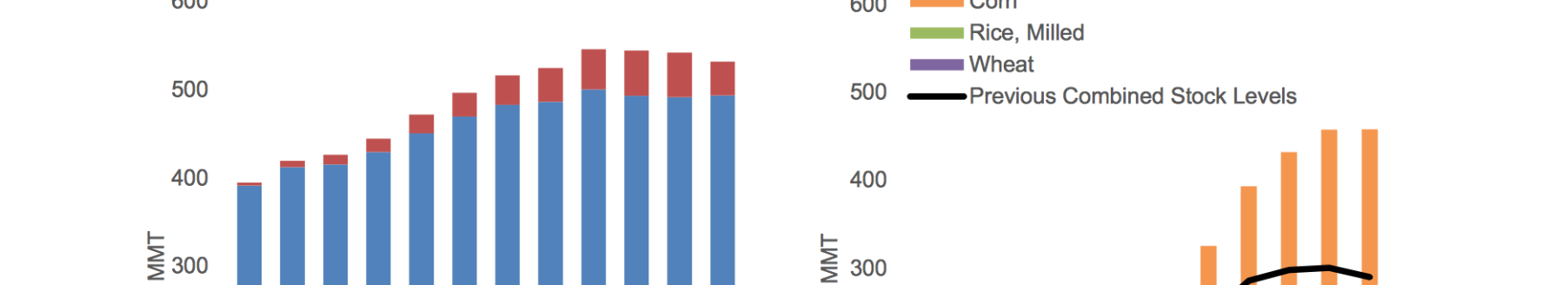

There is no shortage of wheat domestically or globally, but the pandemic has wheat-producing nations weighing various options without an end to the crisis in view, Welch said.

“The future of the wheat crop is raising some concerns, but the U.S. has an abundant wheat supply,” he said. “We have a lot of carryover wheat, and despite wheat acres being down slightly this year, production on those acres is usually very good.”

Another factor that muddies price futures is concern about food grain exports going forward, especially to China. Uncertainty about whether the Chinese can or will follow through with Phase 1 of their trade agreement is one of several factors in flux.