There is an expression, “What goes up must come down,” where at some point, gravity becomes reality.

In production agriculture, the sense of gravity is a familiar theme in many ways. Seeds are “dropped” from a planter into the ground. Harvested grain is elevated up, and then gravity takes over for it to fall into a storage bin. Grain prices rise, and grain prices fall. Since 2019, cropland values have known one direction, up and to the right on a chart, and seem impervious to falling, but are they?

Based on the latest “Ag Credit Survey” released by the Kansas City Federal Reserve in February, while land values continue to increase, they are doing so at a slower pace. Across the 10th District (Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Wyoming, the northern half of New Mexico and the western third of Missouri) of the KC Fed, land values during the fourth quarter of 2023 increased 11% from the previous year, while irrigated and ranchland values were each up 7%.

Double-digit trends

Cropland values were growing at double-digit levels for six consecutive quarters starting in the second quarter of 2021, with four quarters exceeding 20% growth rates. Since the fourth quarter of 2022, the growth rate in cropland values started to slow, while still increasing at absolute levels.

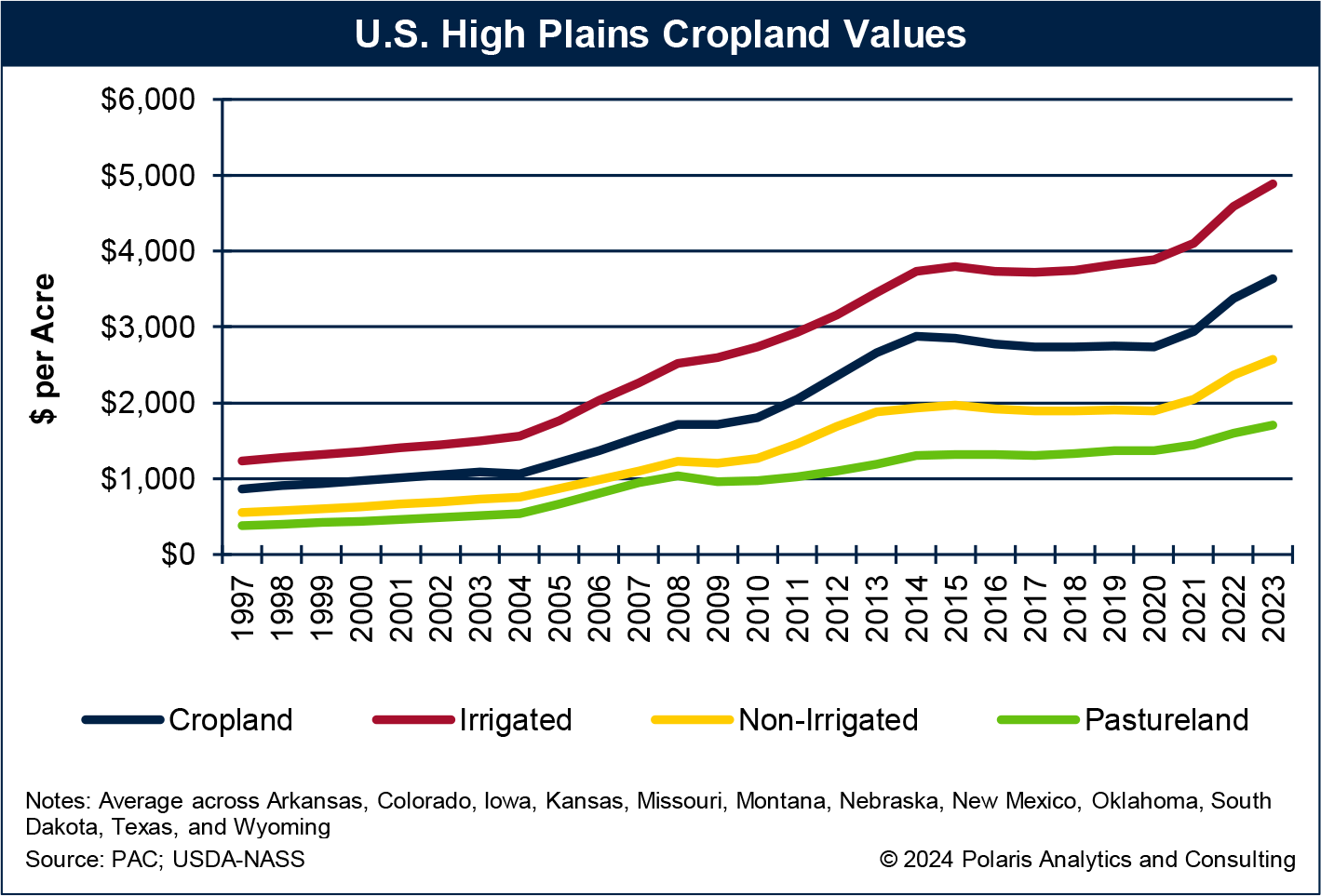

Across the United States, cropland values increased an average of 6% annually over the past five years to $5,320 per acre for 2023 as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the annual “Land Values Summary” report released in August. Across the 12 High Plains states (Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas and Wyoming), cropland values averaged $3,636 per acre in 2023, increasing an average of 6% annually over the previous five years. Irrigated cropland across the High Plains states averaged $4,886 per acre for 2023, while non-irrigated cropland averaged $2,572 per acre and pastureland $1,706 per acre.

The Kansas City Fed will release its next tranche of quarterly cropland values in May. The USDA releases its next land value summary in August and will be surveying farmers and operators during the first two weeks of June.

What’s next?

The question is, do land values reach a point where gravity takes over? If so, what will precipitate the reversal? As mentioned, the growth in cropland values is slowing. Looking back in history, cropland values are not exempt from falling. The last time cropland values turned negative was not too long ago, starting in 2015 and continuing to 2019. Both the KC Fed and the USDA reflected this.

What factors influence cropland values to turn negative? Well, just prior to 2015, the U.S. farmer emerged out of the drought of 2012, that had lasting impacts well into 2013 and early 2014. The impacts were most noticeable on corn yield and corn exports that were at historical lows at 731 million bushels during the 2012-13 crop year. But, from 2015, crop growing conditions improved to near ideal through 2018, leading to large harvests and an abundant supply of grains and soybeans.

Grain prices in turn weakened and remained flat, while interest rates were historically low to lessen the pain of investing capital in grain storage, equipment or cropland. Conditions today are remarkably like those years, but interest rates and inflation are more glaring, and cropland values are record high.

Headwinds

Prior to 2015, the last time cropland values were in steady decline was 1982 through the first half of 1987 when values plummeted a cumulative 67%. During that time, there were 23 consecutive quarters of declining land values. The negative cropland values from 2015 were in 13 consecutive months.

It is hard to believe there could be such a pullback in the coming quarters and years, but with ample crop supplies in the U.S. and around the globe, increased competition from South America, Russia and Australia, population shifts (with China’s shrinking), dietary changes due to persistent inflation and interest rates and inflation being stubbornly sticky, causing many to refrain from financing capital projects and expansion, a bearish cropland value story can readily be promulgated.

This says nothing about the forthcoming presidential election, with both candidates trying to outdo each other using tariffs against countries, such as China, who are economically damaging the U.S., as punishment. If negative cropland values appear soon, what is concerning is how fast such a pullback arrives from the most recent period of negative returns. It was nearly three decades between the two periods of negative growth rates, 1987 to 2015.

Allocating resources

Economics is a useful concept, and when left to do its thing, that is, allocate scarce resources such as commodities among competing terms, the market does its job. When there are scarce resources that are high in demand, prices rise, rewarding those holding the scarce commodity or product. Conversely, when there is an abundance of resources, and the rate of demand is steady or contracting, then prices fall. The same can be said of cropland values.

While gravity is a reality, it is important to bear in mind when it comes to commodity markets, or cropland values, one must keep an eye looking forward, much like navigators who watched the horizon for direction and guidance. Keeping an eye on the horizon is a way to remain on course by keeping oneself well aligned.

This column, named Horizons – At, On and Over the Horizon will be a regular feature in the High Plains Journal to bring attention to key economic considerations affecting markets and the economy and to keep gravity in perspective.

Editor’s note: Many of our readers are already familiar with Ken Eriksen. He has often been quoted as an economist/consultant and a supply chain and commodities expert through his work with Sparks Companies, Informa Economics, IHS Markit and most recently S&P Global. Prior to Sparks Companies, Eriksen worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture after working in the Department of Agricultural Economics of Washington State University.

Now, we are pleased to announce that Eriksen, managing member and strategic advisor of Polaris Analytics & Consulting, will be a regular columnist for High Plains Journal and its sister publication, The Waterways Journal, writing about economic considerations important to agriculture and the inland marine transportation industry. Generally, his column will alternate weeks between the two publications, so you can expect to read it here every other week.