One hundred twelve years ago on Aug. 19, my great grandmother gave birth to twin boys, Marvin, and then, six minutes later, Morris, my grandfather. They grew up and farmed together, with Granddaddy raising dairy cows on the farm where I now live and Uncle Marvin raising hogs on his nearby property.

Over the years, the look of the farm has changed. The Holsteins were replaced first with beef cattle, then sold, with Uncle Marvin and Grandmother driving the last two steers to market in the early 1980s, following Granddaddy’s passing in 1979. I was a very little girl and rode along in the truck with them. They told me we were “taking the cows for a ride.” I never questioned why they never came back, although I peeked into their barn stall several times to check if they might have made a sudden reappearance.

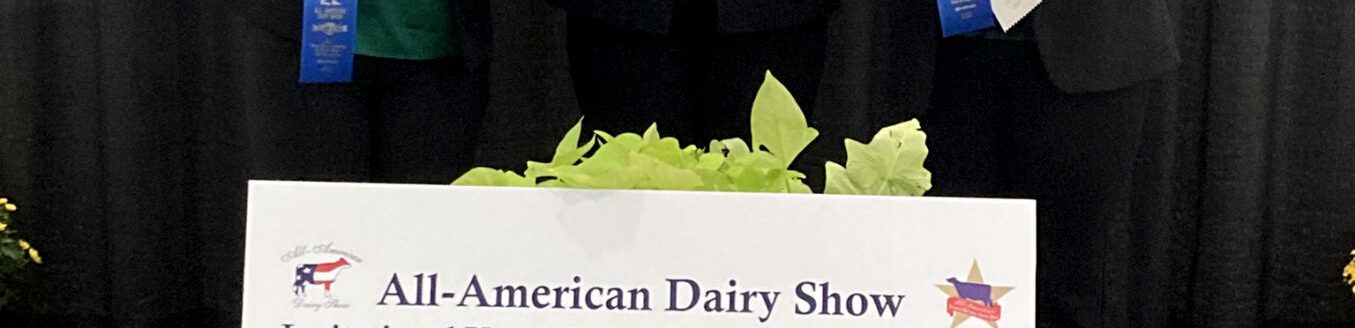

Pictured above is the dairy barn as it appeared in the spring several years ago. (Photo courtesy of Shelley Byrne.)

Barbed wire fences were overtaken by saplings and sticker bushes, and most eventually fell down. The garden shrank. While I spent many summer days snapping green beans, shelling purple hull peas and shucking ears of corn from Grandmother’s enormous garden, we have only a few small containers with tomatoes, onions, bell peppers, cucumbers and carrots.

Soybeans, in rotation with corn, still surround my yard on three sides. Until this spring, Granddaddy’s dairy barn was still standing, too, but it was in sore shape, missing one of the “doghouses” that vented the hayloft along with several pieces of corrugated tin roofing. Over the years, the whole structure started leaning, which was alarming because it was only a few feet from the road. We tried for some time to find someone willing to take the barn down in return for salvaging the wood, but three different people came out and then ultimately were uninterested. Eventually, my Dad made an appointment with a man he knew who had the heavy equipment necessary to take the barn down.

I have been spending my spare time researching the history of our farm, which came into Granddaddy’s hands after first belonging to his uncle and aunt. I found an old newspaper notice from 1932 that announced that a stock barn on what was then his Uncle Robert’s farm burned, causing the destruction of 700 bushels of corn, a large amount of hay and a cow and calf. Presumably the dairy barn I knew was the replacement for that one. It was originally built on the other side of the road, but, around 1938, that portion of the farm was part of more than 16,000 acres seized by the government via eminent domain. The acreage was used for the Kentucky Ordnance Works plant, an explosives manufacturing facility that eventually produced an estimated 196,490 tons of TNT for use in World War II.

A neighbor, Tommy Quarles, stopped by one day and told me more. He said families were given 10 days to vacate the property when it was seized. Granddaddy’s Aunt Daisy, who inherited the farm when his Uncle Robert died, wasn’t about to let the government get her nearly brand-new barn. Quarles’ father, then a little boy, was among the team who jacked up the barn onto a trailer and moved it just across the road for her before setting it on a new concrete foundation.

Twice a day for nearly 50 years, 30 to 50 Holsteins came in the dairy barn to be milked, at first by hand and then with the help of electric milkers. Grandmother and Granddaddy named every one of those cows, eventually with the help of my mother and aunt. Each one of the girls was given her own heifer when she was born and had the right to choose what to do with it: keep or sell. If sold, the money had to go into her savings account. If kept, she would own all that cow’s offspring and all its offspring and on and on. Mama kept as many of them as she could. When she graduated high school, the money from those she sold paid for her first two years of college. She “gave” Granddaddy her remaining cows in exchange for paying for her last two years of school.

On Feb. 20, a trackhoe pulled down the dairy barn. I saved one of the windows, which I made into a photo display, along with a few boards for a possible future craft project. My view from my front porch is now of a pile of concrete rubble, the remains of the foundation, being overgrown by grass. The last sign of the farm’s rich dairy history is gone.

While I’m sad, it helps to remember that the farm has already seen many changes over the years, and while there are endings, there are also new beginnings. My husband, Paul, and I are raising our son, Andrew Marvin, named after Uncle Marvin, on the farm in the same 1921 farmhouse my grandparents lived in. This makes him the fifth generation of my family to live in it. My sister is also building a house on the farm with her husband and their two sons, Kai Ronen Knight and Kristopher Kent Morris, next door to where our parents, Ronnie and Karen, built their home.

Our boys enjoy swings, slides and trampolines, ride bicycles or tricycles or settle down in hammocks in our yards. We watch the stars and the seasons change from our patios and still gather around my great grandmother’s dining room table to say the blessing and eat.

Even with the barn, cows and fences gone, our farm family lives on, still making use of the land, remembering the lives of those we have lost and raising the next generation with a love of the land and of family. I think Granddaddy and Grandmother would both be happy about that.

Shelley Byrne, copy editor for The High Plains journal, lives on her family’s farm near Kevil, Kentucky.