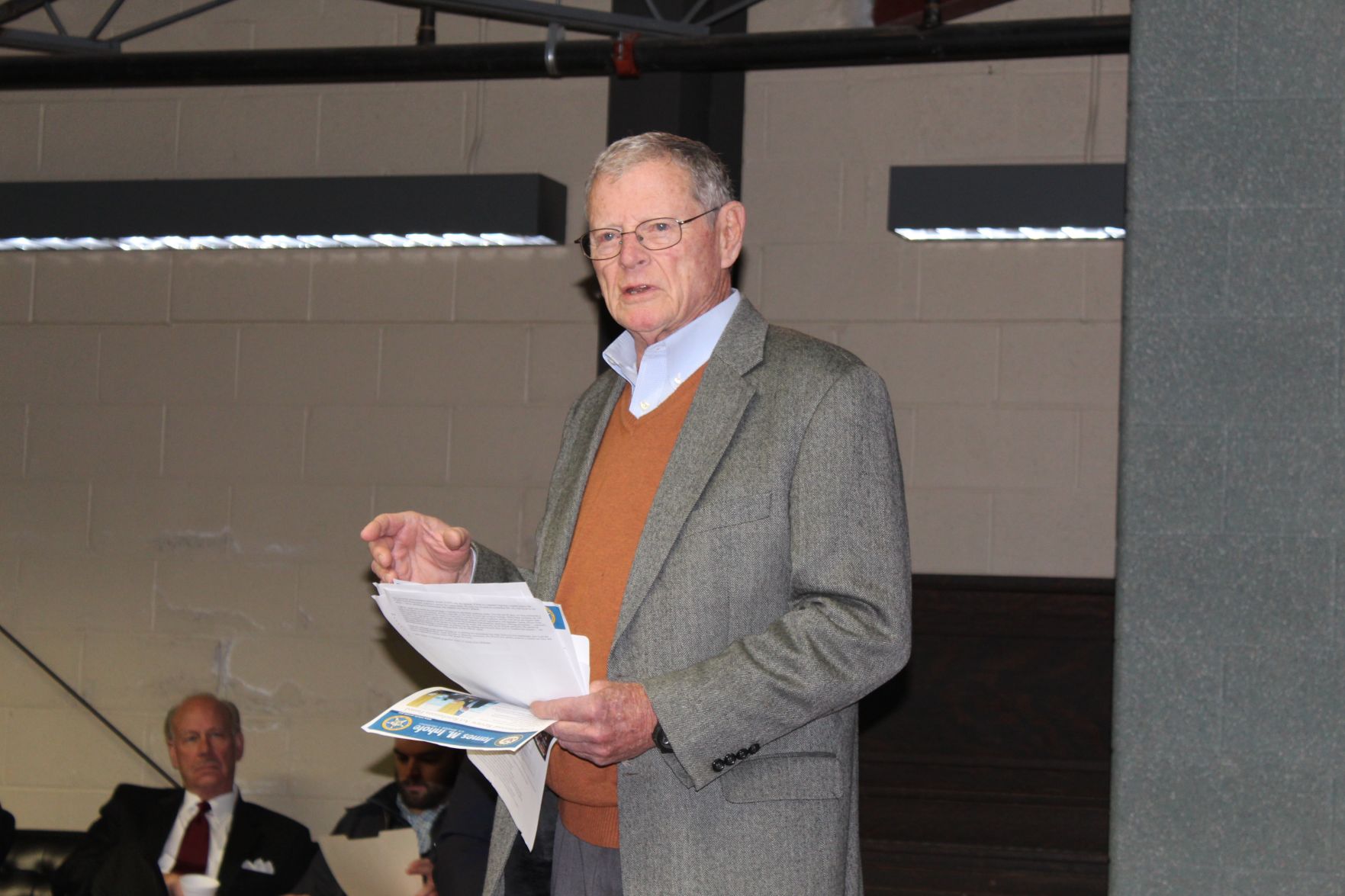

Sen. Inhofe, ag leaders detail Wildfire Regulatory Relief Act

Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-OK,, explained the Wildfire Regulatory Relief Act at the AFR Farm and Ranch Forum during the KNID Agrifest, Jan. 12, in Enid, Oklahoma. As part of the discussion, Inhofe led a panel of Oklahoma rural leaders who helped craft the legislation at the grassroots level. The panel included: Oklahoma Cattlemen’s Association Executive Vice President Michael Kelsey; State Executive Director for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Oklahoma Farm Service Agency Scott Biggs; President and CEO of the Bank of Laverne David Cook; and Director of National Affairs for Oklahoma Farm Bureau LeeAnna McNally.

Inhofe co-sponsored the legislation with Sen. Tom Udall, D-NM, which is intended to improve federal wildfire disaster response in farming and ranching communities. It’s intended to fix many of the bureaucratic hurdles that farmers, ranchers and their rural community lenders faced following the Anderson Creek Wildfires of 2016 and the Starbuck Wildfire of 2017.

The act would:

• Allow grazing on Conservation Reserve Program land during a disaster;

• Include fence line as well as residential and community infrastructure in FEMA disaster assessments for consideration for federal assistance;

• Encourage collaboration between state and federal agencies for more effective communication and firefighting collaboration; and

• Grant banks greater flexibility to aid disaster recovery by rolling back some Dodd-Frank provisions.

Inhofe said when he visited Woodward, Oklahoma, last year in the midst of the Starbuck fires, he spoke with rural farmers, ranchers and community leaders who were not just fighting the flames but government red tape.

“Banks were prevented from lending more money to their customers to recover, and federal aid was slow and insufficient because of bureaucratic red tape,” he said. For example, by requiring the Federal Emergency Management Agency to include damaged fences and farm and ranch property in their disaster assessments, a national disaster declaration can then be triggered. That designation means the wildfire that damaged a sparsely populated rural area with more farms and ranches than residences roughly the size of Delaware gets treated by federal agencies similar to a natural disaster that hits a smaller yet more densely populated area.

Kelsey explained that OCA members lost fences ranging from one-quarter mile to 150 miles. At roughly $10,000 per mile to replace, that is a loss comparable to losing residences in a populated area.

“FEMA didn’t declare this a national disaster because they can only count residential and community structure losses,” Kelsey said. “We didn’t have enough homes destroyed to declare. This is an important piece of this legislation to count fencing so that we can trigger federal program response.”

Another critical aspect for OCA members, Kelsey said, is the provision to allow emergency grazing of CRP land, and not only in the area hit by the same disaster.

“In our opinion, CRP acres should be working lands, and not complete set-aside lands,” Kelsey said. Grazing is already allowed in response to flood or drought, and wildfire should be covered too. And it’s important that the provisions extend to CRP acres that are not in the immediate wildfire zone.

“The CRP acres in the area were likely hit by the same disaster,” Kelsey said. Opening up more acres outside of the fire zone helps ranchers feed their cattle and save herds.

Cook said his bank is small by some measures, but it is the local lender to large producers. Much of the collateral his ranchers had for their loans burned up.

“We had more than 2,000 acres of one ranch burn, with 150 miles of fence,” he explained. While producers applied for FSA programs for reimbursements for fencing and livestock, the reimbursement doesn’t fully replace the amount of collateral lost.

“We had one producer lose 150 bred momma cows in the fire,” Cook said. “At a reimbursement of about $948 per cow, that doesn’t replace the collateral he lost, that we lost.”

Without a FEMA declaration, banking regulators don’t have guidance how to advise lenders in how to deal with their affected customers, Cook said. There is no FDIC forbearance memo sent to bankers or leeway from regulators in a wildfire that hits ranching country, unlike in a hurricane disaster that hits a major populated area. This act addresses that, Cook said.

On the minds of everyone was what will happen this coming spring and the potential for yet another devastating wildfire to hit ranching country. Kelsey reminded farmers that the countryside is set up to have just as bad of a disaster this coming year because of the good rains last year that gave good regrowth in pastures and CRP acres.

“We had those good rains that helped us recover after the fire and allow us to have some regrowth,” he said. “But that also increased our fuel load.” OCA members are working on ideas to help mitigate the coming fire season.

OCA and other cattlemen’s groups in the High Plains already have the infrastructure in place to coordinate hay, fencing and monetary donations, sadly having learned what works and what doesn’t from the last two years of wildfires.

But there are ideas of how to stop the flames before they can spark. For example, Kelsey said, the idea of shutting off power lines in rural areas during high wind days.

“We know that the fires last year were sparked by power lines blowing together in high winds and sparking,” Kelsey said. “Well, when we ask farmers and ranchers if they’d be OK with us shutting off power for 10 to 20 hours in high wind situations when it’s dry and there’s a high fuel load, many are on board.” OCA is working with electric cooperatives to investigate the merits of the idea.

Another tactic might be to manage the fuel load by encouraging more grazing in some areas, and grazing CRP that might be carrying high fuel loads that can feed the fires.

The bill was introduced to the Senate Jan. 11 and is now in committee. Read the full text of the bill here.

Jennifer M. Latzke can be reached at 620-227-1807 or [email protected].