Pasta wheat varieties could be released by K-State within 5 years

For more than 140 years, Kansas has been known as the nation’s breadbasket.

Yet, on a hot afternoon in June, Kansas State University’s Northwest Area Agronomist Lucas Haag walked past the ripening hard red winter wheat to a swath of research plots that he says could be the region’s next cash crop.

Pasta.

While K-State continues its work on improving winter wheat varieties, near Colby, Haag and others at the university are also developing winter durum varieties that could be used to create macaroni, spaghetti or another of the 350 pasta shapes available.

And someday soon, farmers could have a new alternative to add to their rotations—a crop that could potentially add more cash to their pocketbooks, Haag said.

“The K-State wheat breeding program has been working on this well over a decade, trying to develop a winter durum,” Haag said. “This is the first winter durum that is adapted for our part of the world—the Great Plains.”

Market opportunity

There are six classes of wheat, with Kansas growing mostly hard red winter, plus hard white varieties. Durum, however, is the smallest in terms of United States production, according to the U.S. Durum Growers Association.

However, demand for durum continues to grow from pasta companies because it has higher gluten and protein content compared to wheat, said K-State Wheat Breeder Allan Fritz.

Fritz and assistant agronomist and durum breeder Andrew Auld are working to create a winter durum with enough winter hardiness to survive the High Plains climate.

Fritz said he sees an opportunity for Kansas to be a player in the market through the development of winter durums.

The majority of durum genetics is in spring varieties, he said. The largest U.S. acreage is in North Dakota, followed by Montana, California and Arizona.

However, in the desert of Arizona, where there are increasing demands for water, durum production depends on irrigation. Meanwhile, spring durums planted in the north are susceptible to Fusarium head blight, or head scab.

“Our durums will still be susceptible to head scab,” Fritz said. “But Kansas has a drier environment, making western Kansas less conducive to scab development.”

Kansas could provide another grain source to millers at a different time the cycle, he said. Millers also won’t have the transportation costs of trucking durum from California or Montana.

Different than wheat

Durum has fewer tillers and bigger heads and seeds than wheat, Haag said. Protein content averages about 13 percent.

The crop uses about the same amount of water as wheat, but Haag noted irrigation is a key to managing the crop’s nitrogen needs.

Millers, he said, “have a narrow range of acceptable proteins. You can have too high of protein or too low of protein. So because of that and needing the ability to time that nitrogen and move it in to hit that protein target, where we think durum will really benefit is limited irrigation acres. On dryland, we don’t have control of nitrogen to get that protein target.”

Haag said they are applying about 4 to 6 inches of water in their research plots.

There are benefits with durum, Fritz added. Because it isn’t a water-intensive crop, durum could be part of the rotation to help preserve and extended the region’s dwindling Ogallala Aquifer.

Durum also is, on average, 50 cents to a $1 more a bushel than wheat, he said.

K-State studies

Fritz said the program averages 300 crosses a year.

In all, they work with about a thousand new potential varieties annually, selecting which ones will perform. From that, he and Auld whittle it down to 200 lines in preliminary trials and 20 lines in advanced trails.

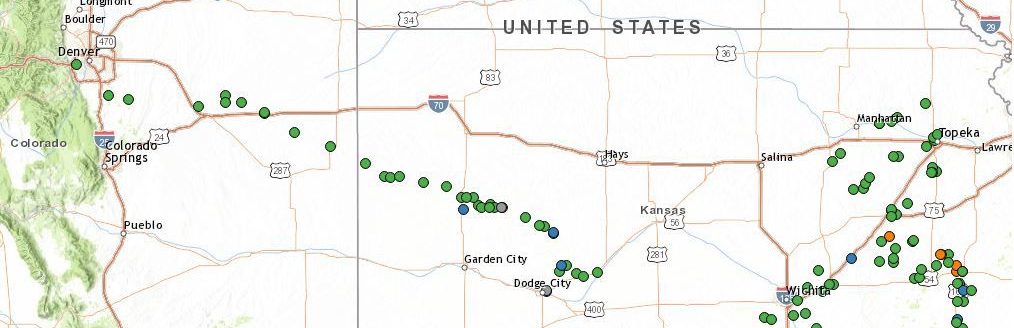

The relationships between seeding rates and planting dates are part of the K-State studies, Haag said. At Colby and two other western research sites, durum is seeded in after high-moisture corn and after mid-season or full-season hybrids are harvested.

“As we get later, it will take more seeding rate to compensate for the reduced tillering,” he said. “But with durums, we think there is probably a point of time where it is like “no, we probably should not be planting past a certain date because it won’t be tillering enough. That is kind of what we are trying to figure out.”

K-State isn’t the only one to try to develop a winter durum.

Ray Brengman, while working as a sorghum breeder at K-State, began developing winter durum varieties on his own in the late 1990s. He brought his research back to his family farm near the southwest Kansas town of Lakin.

Brengman released a few varieties, Fritz said.

There are a few winter durum programs in other countries, too, but even those varieties aren’t bred for the Great Plains, Fritz said.

A western plains alternative

Fritz said originally the crop was targeted for western Kansas south of Interstate 70 because of the concerns for winter hardiness. But he expects as the breeding program continues there will be options to grow durum further north.

“I think we can get better winter hardiness over time,” Fritz said.

It will be two to five years before a K-State variety is released, he said. Varieties released must be a good quality from both an agronomic and end-use perspective.

“A lesson from white wheat: don’t put something out there that isn’t quite ready to go,” he said, adding the goal is to find varieties that producers will be happy with. “There is a danger to push it out too fast. There is an interest to get it out there, but we want to err on the side that what we have is a good fit.”

He already is talking with end users about the breeding program.

“We think it is a good option here,” Fritz said. “The positive is, we don’t have to buy specialized equipment. The drill we use for wheat will work.”

He and Auld harvested the crop in mid-July at Colby using a blend of hard red winter wheats Grainfield and Monument and white wheat variety Joe as a check.

“Some of the preliminary lines and advanced lines were as good or better than that check, and I think those are three pretty good varieties,” Fritz said. “I think we are yield competitive. We just are making sure we have the quality we need.

“I do think five years from now we will have a release,” he said, later adding, “We want to be the provider of high-quality durum.”

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].