Every year since the 1870s, when turkey red wheat was brought to the Kansas plains, farmers have planted a wheat crop, harvested it, then planted it again in the fall.

But that annual farming cycle could change for some farmers if a close perennial cousin takes hold.

Not that Kernza, as it is called, has gained much ground in the Midwest. At least, not yet. About 700 acres of the intermediate wheatgrass was grown this year. But Lee DeHaan, the lead scientist developing the crop at the Salina, Kansas-based Land Institute, sees it as a crop for the regenerative agriculture movement.

The deep-rooted plant builds soil health, curbs water runoff, sequesters carbon and enhances wildlife habitat.

It mimics the prairie ecosystem that conventional crops replaced.

“I think it is a good idea not to have to till and plant every year,” DeHaan said from a greenhouse where he had started a new crop of Kernza seedlings just a few days before.

He got out a hose and watered them, noting in coming months he and his team will use sequencing to help select the best plants based on traits such as yields, hardiness, seed size and disease-resistance. The result is improved populations that are currently being evaluated and further selected by Land Institute scientists and collaborators in diverse environments.

“It’s been 30 years in the making,” he said, adding there is still a long way to go.

Yet, DeHaan is living his dream. While some kids dreamed of being a baseball player when they grew up, DeHaan wanted to develop perennial grains.

DeHaan said his father, a Minnesota farmer, heard Wes Jackson speak in the early 1980s. Jackson, a co-founder of the Land Institute, was an advocate of perennial grains, touting the difference between soil health on farm ground and the native prairie.

“I heard about it when I was a kid, a teenager maybe,” he said.

But DeHaan never fathomed he’d wind up at the Land Institute. He did, however, end up there in 2001 as part of the graduate research program. Upon graduation, Jackson offered him a job.

“It’s the only place in the world I can work on perennial grains, so I had no choice,” DeHaan said with a smile.

Kernza is born

In 1983 the Rodale Institute, an organic farming organization in Pennsylvania, was inspired by Jackson’s vision for perennial grain crops and surveyed 100 different species for a potential candidate, DeHaan said. Researchers selected intermediate wheatgrass and began a breeding program in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which had the Eurasian forage as part of its collection.

From the late 1980s to 2000, researchers undertook two cycles of selection for improved fertility, seed size and other traits in the state of New York.

“We obtained the seed from them in 2001 and picked up where they left off of it,” he said.

When DeHaan came to Kansas, he began to work with the institute’s perennial wheat program.

That program has had limited success because the hybrids tend to not make it through the winter.

“If we can achieve it, it will be a great breakthrough,” he said. “It will have much higher yield and bigger seed and higher quality.”

The hybrids yield well, but he added perennial wheat “doesn’t really exist. But these hybrids that don’t persist very well can yield 70 to 90 of a wheat crop.”

DeHaan said he shifted his focus exclusively to Kernza in 2010, feeling his calling was to domesticate it.

Kernza is a name DeHaan and the institute “made up,” he said.

“We were looking at marketing products, and people were telling us we needed to call it something unique. We wanted those who are growing it, those who are marketing products out of it, to know what it is.”

Kernza is a combination of kernel and Kanza. Or, in essence, “grain from Kansas,” DeHaan said.

“We thought it sounded grainy,” he said. “We searched on the internet and there was no other word like that for anything.”

The name is trademarked, he said.

Improving Kernza

While perennial wheat doesn’t yet exist because it has a difficult time surviving, Kernza’s biggest setback so far is yield.

“The yields are highly variable,” DeHaan said. “That is one of the biggest issues we face is trying to figure out what factors are influencing the yields from field to field and year to year. There are a lot of mysteries there and opportunities for research.”

With a dry winter and spring, this year’s crop at the institute’s farm was poor. However, forage yields are good, he said.

Farmers can get two to three cuttings of hay. At the highest, 4 tons of biomass an acre is possible.

“It’s good for beef cattle over the winter,” DeHaan said. “But it is not something you’d want to feed a dairy herd.”

DeHaan said farmers can plant it like wheat in the fall and use the same equipment to harvest it. The goal is to have a stand that will be productive for five years.

“The track record hasn’t been great yet,” he said, adding some stands last about three years before they don’t have a decent grain yield anymore.

“It still has a good forage yield, but it is producing smaller heads, smaller seeds,” he said.

Kernza beer

While DeHaan’s work continues to craft better hybrids of Kernza, the grain is being grown commercially for artisan bread and beer.

Patagonia Provisions was the first to develop a retail product about four years ago, crafting Long Root Ale.

Breweries in other states also are incorporating Kernza into their recipes, including Blue Skye Brewery in Salina, DeHaan said. Restaurants are serving products made with Kernza.

Meanwhile, Cascadian Farms, an organic food company under General Mills, is planning to help commercialize organic Kernza next year, DeHaan said.

The Land Institute also gauges interest locally, serving Kernza products, including pancakes, at its annual Prairie Festival.

The limited grain supply, however, makes it tough to have a consistent market. He noted the Salina brewery can’t offer its Crank Case IPA because of the quantity available.

It’s part of the reason the Land Institute is adding a commercialization manager to its organization. The position would promote Kernza and help create a farmer base around potential market hubs, DeHaan said.

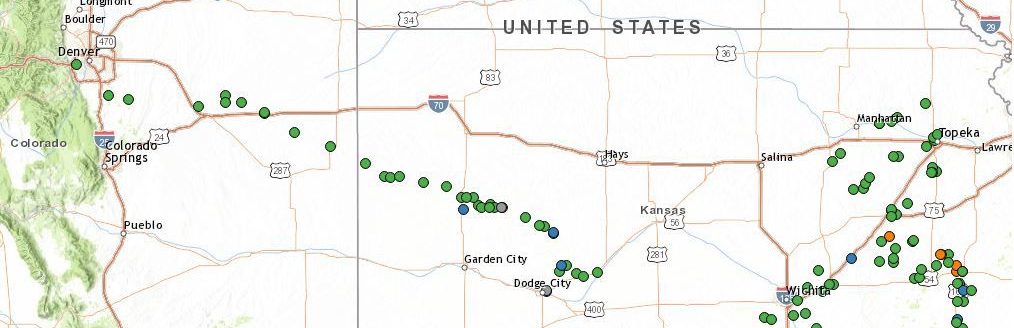

“Most of the farmers growing Kernza are experimental in size,” he said. “That is why there are only 700 acres. There are people planting 5, 10 or 20 or 30 acres just to try it out.”

Much of the acreage is grown in Ohio, Minnesota, the Dakotas and the West. Kansas is the farthest south it can be grown. He said a family near Ellsworth is growing 30 acres.

The goal is to develop a strategy of where to grow it, where it does well and pair that information with transportation and processing.

“With only a few hundred or few thousand acres, in order to make it economical, we can’t have it scattered all over the place,” he said. “We have to be more strategic about seeking out farmers in particular regions that will be the best fit.”

DeHaan said there are many small mills around the country to process Kernza. But finding places to clean the seed is a bigger issue.

Interest continues to grow and DeHaan has a list of people interested in Kernza. However, there is still plenty of work to be done before Kernza can have any significance in the grain market.

“We want to be cautious for the sake of the project and for the farmers involved,” DeHaan said.

“For farmers, this is very different than any other crop they have ever grown. So there’s a big learning curve that is going to happen. It is not something they are going to dive into and have a big success with it the first year. It’s something you are going to have to commit to learning for multiple years and gaining knowledge and experience and gaining confidence with it over time.

“It will be exciting to see in the next few years to see where the expansion goes,” he said.

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].