Kansas State University researchers are evaluating the impact of non-target injury from dicamba herbicide on non-resistant soybeans. The hope is to help producers lessen or avoid the unintended damage that was seen in some of the state’s fields the past two years.

Their work comes on the heels of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently renewing its registration of Xtendimax, FeXapan and Engenia, the three dicamba herbicides that are approved to be sprayed on tolerant (Xtend) varieties of soybeans and cotton. Non-tolerant soybeans are extremely susceptible to dicamba, causing injury to plant leaves and reduced yields.

“The critical factor is when and how we use the dicamba,” said Dallas Peterson, a weed management specialist with K-State Research and Extension. “An early-season application poses much less risk of causing a problem, and if we do see a little bit of non-target injury from those early-season applications, the long-term impact will be much less.”

Peterson conducted the work with colleague Vipan Kumar, a scientist at the Agricultural Research Center in Hays, and graduate student Tyler Meyeres. Among their findings, they were able to confirm that injury to soybeans was at its lowest level when dicamba was applied during the vegetative growth phase.

“Just because you see injury doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re going to see yield loss,” Peterson said. “However, that still doesn’t make it right; we still don’t want to have to worry about non-target injury.”

He added that researchers strongly suggest that producers closely follow label directions when applying dicamba, and “be aware of surrounding susceptible crops and plants to minimize the potential for off-target movement.”

“In fact, producers shouldn’t even spray the products if the wind is blowing in the direction of neighboring fields or areas with susceptible crops and plants,” he said.

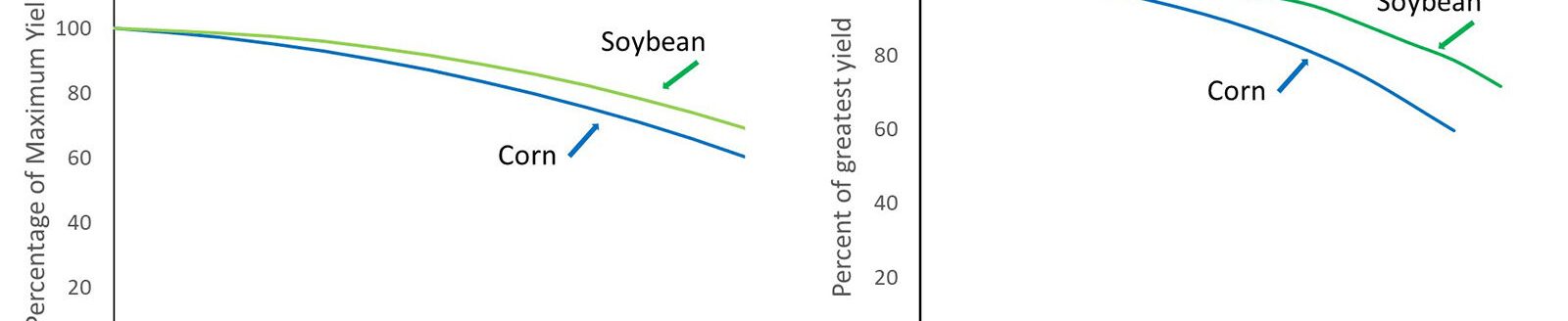

Peterson noted that injury to soybeans and resulting yield loss was much higher when soybeans were exposed to dicamba during the reproductive phases, which was an expected finding. That was also the case when fields were exposed to dicamba applications multiple times during a growing season.

“When there were multiple exposures of soybeans to dicamba, crop injury and yield loss increased dramatically,” Peterson said.

For example, in a research setting, when the K-State group exposed soybeans to 1/100 of a typical field-use rate at all three growth stages, soybean yield was reduced by nearly 70 percent.

The researchers also evaluated dicamba rates of 1/500 and 1/1,000 the normal field use rate. Peterson said soybean yield loss from those rates was much less than at the 1/100 rate and often not significant.

“Unfortunately, injury symptoms on soybeans can occur at rates down to 1/20,000 and it’s impossible to know what the exposure rate was,” he said.

“Dicamba has been beneficial from a weed control standpoint,” Peterson said. “But we don’t want to rely just on dicamba or we’ll have the same problems with resistance to dicamba that we experienced with glyphosate. So good stewardship and using an integrated weed management program is extremely important.”

He adds that producers should “communicate with your neighbors, follow the application guidelines and make good judgments when you apply and how you apply dicamba products.”