Husker scientist leads effort to understand, adapt legume nitrogen conversion

Soybeans and other legumes interact with nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria called rhizobia that are able to convert nitrogen in the air into a form the plant can use to grow and reproduce.

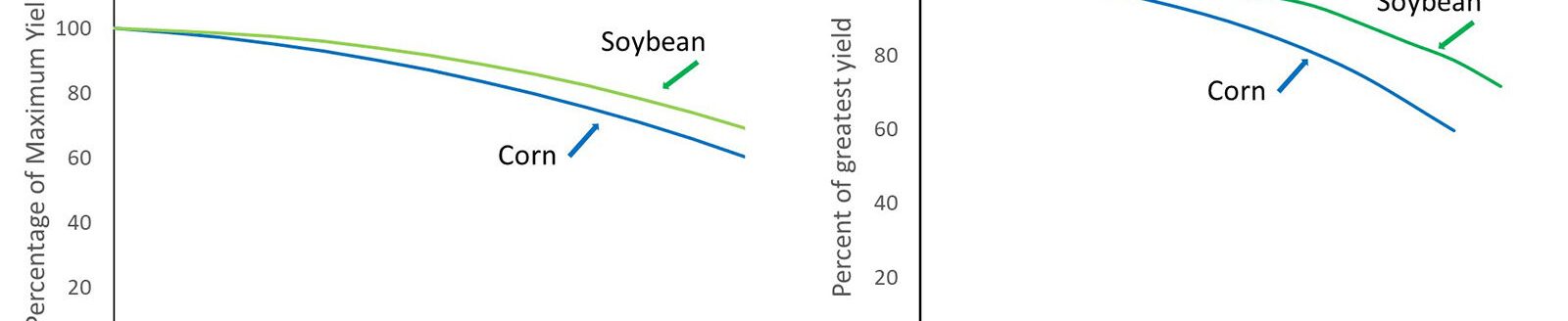

Corn and other crops can’t, requiring nitrogen fertilizers to maximize growth and yield—problematic because overapplication or runoff can pollute soil and water.

Researchers are trying to find alternative, sustainable sources of nitrogen to solve that problem.

“Can we transfer this capability to non-legumes?” asked Marc Libault, a University of Nebraska–Lincoln plant scientist.

Libault leads a multi-institution research team seeking to better understand how legumes strike up such a productive partnership with a group of bacteria called rhizobia, which convert atmospheric nitrogen to a chemical form that supports the host plant.

“This biological process, called nodulation, is economically important and benefits agricultural sustainability and food security,” said Libault, associate professor of agronomy and horticulture.

It begins with the infection of the plant root hair cell by rhizobia. Although this cell type is found in nearly all flowering plants, in only a subset of plants—among them legumes—is the root hair cell capable of initiating this symbiotic relationship.

“While several legume genes involved in this process have been characterized, a better understanding of the genetic programs controlling root hair infection by rhizobia is needed before considering the transfer of nodulation capacity to non-legume crop plants,” Libault said.

In addition to soybeans, researchers will study medicago, a genus of flowering plants that includes alfalfa, and common bean.

Libault’s team will characterize these genetic programs using plant single-cell technologies. In addition to its impact on scientists’ understanding of legume nodulation and biological nitrogen fixation, this project will promote the integration between research and education by supporting development of STEM educational programs for high school and undergraduate students.

Ultimately, researchers might be able to genetically modify non-legumes such as corn, rice and wheat to give them the ability to attract rhizobia and fix atmospheric nitrogen. Using less fertilizer could not only reduce pollution, but significantly decrease farmers’ input costs.

Libault said the project is built on the hypothesis that plant cell differentiation, gain of biological functions and response to external stimuli are controlled by evolutionarily conserved transcriptional modules. Working on three legume species will help reveal these modules.

The investigators will analyze the molecular mechanisms associated with the early stages of the nodulation process by studying one by one the biology of isolated legume root hair cells. Accessing changes in both gene activity and the profiles of chromatin accessibility will provide a deeper understanding of the dynamic response of a plant cell to microbial infection and the level of conservation of these responses among legume species and upon whole-genome duplication.

The University of Nebraska–Lincoln has prioritized research into sustainable food and water security as one of its Grand Challenges. It was named a priority because of the university’s expertise in this area, and the impact Husker research can make on more sustainable agricultural production.

Libault, who is affiliated with Nebraska’s Center for Plant Science Innovation, is working with colleagues from Cornell University, the University of Michigan, Reed College and the National Center for Genome Resources. The work is funded by a $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation.