The root of the stalk determines the health of the plant. It doesn’t matter if you are talking about a wheat plant or a human being. Our challenges today stem around the fact that too many folks have lost that connection with their roots.

Recently I spent the weekend with a group of families in touch with their roots. The U.S. Custom Harvesters have just concluded a successful convention in Amarillo, Texas, and I enjoyed my time with these people. Like all things in life, I think it is worthy to take a look back at how the whole endeavor got started.

What was top of mind in concerns for the wheat harvesters is what the impact of the drought will be for the upcoming harvest. The concern that overrides all of that is how extreme will government regulations be, including being licensed to simply drive down the road and who will be eligible to work or finding willing help. I feel it needs to be said that when folks on the outside hear talk about custom harvesters, wheat tends to be the first image that comes to mind. However, these harvesters are just as involved in forage harvesting for ruminant nutrition as they are wheat for your biscuit.

First, let’s start with the current labor shortage. Short staffing is nothing new in the harvesting world. In fact, I could make the argument that lack of manpower is what created the entire custom harvesting industry. The bumper crop of 1942 created problems because so many young men were involved in fighting during World War II. In fact, “Beating Wartime Restrictions: Massey-Harris’ Harvest Brigade” tells us the following:

“In the United States, the harvest tallied more than 3 billion bushels of corn and close to a billion bushels of wheat. In Canada, it amounted to more than a half billion bushels of wheat. In spite of these huge harvests, millions of the world’s people faced starvation because of the war’s devastation, and rationing of most food items was imposed in both countries.

“The U.S. War Food Administration set a 1944 goal of 1 billion bushels of wheat; even though thousands of farmers were serving in the Armed Forces and existing harvesting machines were worn out. Implement makers begged the War Production Board for a larger share of scarce raw materials so that badly needed new harvesting machines could be built, but the WPB couldn’t promise much help. The same situation existed in Canada.

“So back to the problem of harvesting all that wheat in the U.S. Joe Tucker presented a report to the War Production Board (who controlled rationing in the U.S.) saying that if they would allocate steel, rubber etc., that Massey Harris would build 500 machines that would be dedicated to the 1944 U.S. grain harvest. Each prospective purchaser would have to commit to harvesting 2000 acres with each machine. In order to harvest that many acres the combines would have to start harvesting in Texas in May and continue moving north all summer to end up in North Dakota, Montana or Canada. The War Production Board approved the plan.”

So as a direct result of the war, the U.S. Custom Harvesting business was born. I liken it to the origins of the community itself. Back in the pioneering days, each family could not own all of the equipment needed to get the job done so they relied on friends in the community to come together for big tasks like planting and harvesting. In fact, I could make the case that this was the epitome of the rural community that can still be found today in places where community brandings take place. Honestly, it is as much about the camaraderie as it is about getting the job done but knowing that your neighbor is there for you has important intrinsic value.

The other point I stressed to the custom harvesters was they have the opportunity, in community after community, to be advocates for the concept of domestic food production as a means of national security. Every single custom harvester wears a logo and farm name on their shirt, jacket or cap. I know for a fact that opens dialogue that otherwise would not have taken place.

At the end of the day, this is the group that harvests the crops that feed the world. Whether we like it or not, in 2022 and beyond, we must fight for the right to feed the world and that is one harvest crew I am proud to be a part of.

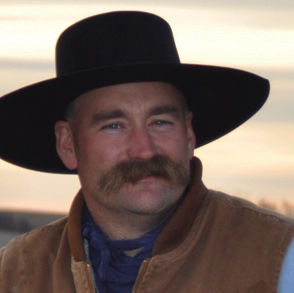

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not represent the views of High Plains Journal. Trent Loos is a sixth generation United States farmer, host of the daily radio show, Loos Tales, and founder of Faces of Agriculture, a non-profit organization putting the human element back into the production of food. Get more information at www.LoosTales.com, or email Trent at [email protected].