Developing, executing a contingency plan can help ranchers reduce stress

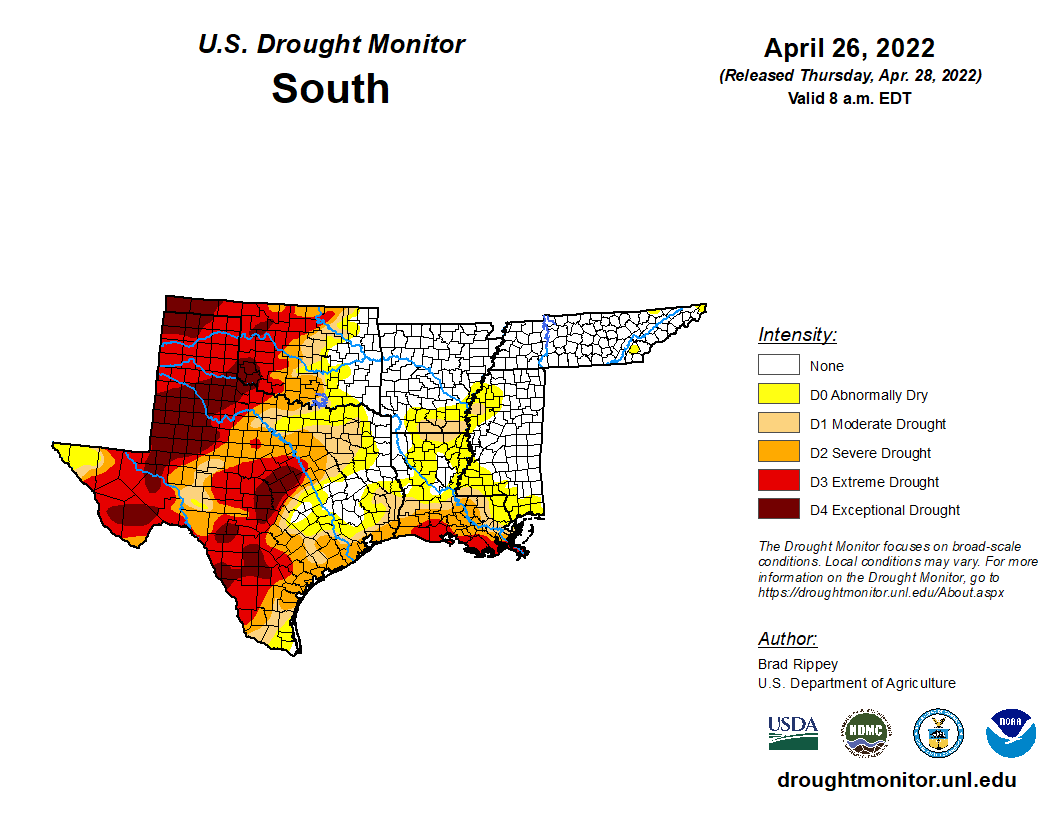

Managing a livestock operation is difficult but persistent drought adds to the stress. Jeff Goodwin, program director of Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute, College Station, Texas, said the latest drought maps show the stress on pastures in the West, central Plains and Oklahoma and Texas.

Goodwin was one of three presenters during the April 21 “Defeating Drought, Rain or Shine” webinar by the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Goodwin was also a rangeland specialist at the Noble Institute in Ardmore, Oklahoma, and for more than 20 years has been working with producers to implement stewardship-based management plans. As of April 19, he noted the drought had continued to spread across many regions.

When extended periods of drought occur producers know what that means for forage production, Goodwin said, saying it is similar to 2011. “We need rain,” he said. Even with above normal rainfall, forage production is expected to be reduced. One forage predictor model has indicated that forage production could be reduced by 15% to 30% in Oklahoma and Texas.

Other presenters were Bob McCan, a rancher and general manager of McFaddin Enterprises in Victoria, Texas, and Coby Buck, a rancher and director of strategic accounts with AgriWebb, an Australia-based livestock farm management software company.

All three agreed that having a detailed drought management plan is essential with target dates. Goodwin said contingency plans are effective in dealing with floods and other challenges farmers and ranchers face. A drought plan needs to have trigger points so a rancher knows clearly what he needs to do and have spelled out options.

Goodwin starts his drought plan based on projected water availability and not on a calendar year. In many areas of Oklahoma and Texas the water year starts in the fall and 25% of the expected rain occurs between Nov. 1 and April 1. If there is shortfall then a producer needs to look at his contingency plans. For example, if a producer expects 50% of his forage to be in place then by the second week of June and he may need to have had 22 inches of rain. By July 15 if he has an expectation of 75% of his forage production in place then he needs to have 67% of his total rainfall.

Goodwin said throughout the process one expectation is that it may not be about reducing herd size but reducing stocking rates. Forage means pounds, but reducing the forage demand during a drought is likely to mean less pain in the future. Having a good inventory of forage is a plus.

“Have a plan and always be thinking two steps ahead of the problem,” Goodwin said, with an important provision that the rancher must be willing to act on the information. He said making arrangements for leased pastureland in advance can also take the pressure off. Overgrazing, he said, hurts the ranch operation in the long run.

McCan believes strongly in rotational practices that for him started in the early 1990s. He has divided pastures and uses a paddock strategy.

When moisture is ample, McCan said he will move the cattle through the paddocks quicker. When conditions are dry, they slow the pace. While a producer has the option of culling cattle, McCan said, he has to keep in mind culling may impact the genetic pool for the herd. March to May is the critical time in the decision-making process for his ranch.

He developed a stocker program that can dovetail with the operation as a way to diversify his revenue stream. He said the bottom line can look good for one year during a culling cycle, which is why he prefers a cash flow plan. The ranch also has a hunting operation to generate additional revenue. According to the ranch’s website hunting opportunities include whitetail deer, feral hogs, geese, ducks, dove, sandhill cranes, turkey and coyotes.

McCan says while wildlife does not consume as much forage as livestock it does have an impact so harvesting offers both benefits. McCan says when dry conditions occur it means taking a closer look at each head, including young heifers. If the drought lingers he will wean calves in mid-May and lighten the nutrient requirements before the heat arrives.

McCan also encouraged ranchers to never stop learning and incorporate new practices that make sense. Over the years the ranch has upped its big bluestem grass to about 20%. He remembered there was a time when little existed on his ranch. He has emphasized soil health and ranch managers are looking at biodiversity projects that could include tapping into carbon markets but it requires detailed records.

One reason he recommended AgriWebb was that it can help with projecting forage growth, and related software tools can help him be a better manager.

Buck is a fifth-generation producer in a family operation in northeast Colorado that is perennially dry. He grew upon the Wray Ranch, which also includes Sandy Chop hills of northeastern Colorado. The family has significant ranchland in the nearby Nebraska Panhandle. The region typically gets about 17 inches of moisture a year, which means a few inches of additional rainfall increases forage production. When it falls under the threshold, he implements a drought plan.

He agreed with the other presenters that developing a drought management plan is essential and he and his brothers look to update theirs on a yearly basis. The past three years have included capturing forage and grazing data so good decisions can be made on stocking rate, cattle inventory and forage capacity.

His key dates are March 1, June 1, July 4, and Aug. 15 as dates he termed as critical rain dates and also for management decisions. Calving occurs around March 1 and goes into April. The operation looks to calve close to the base operation if a dry year is expected and where feed is available. It may also be a time to replace unproductive heifers.

June 1 is an important date because branding occurs and there is interaction with all the cattle. The last two dates are when decisions are made on whether to shorten the breeding season and fall preparation, respectively.

His family’s operation does not buy hay but looks for options to grow additional hay. Buck’s operation includes several irrigated grass fields and that means the capability to retain more cows.

“That is an escape valve when we need it.”

Buck also told ranchers to not be discouraged and remember neighbors and family are also being impacted by drought.

“Whether it is family, neighbors or friends, look out for them,” Buck said. “Try not to bring the drought into the house and look to take time off. Working harder won’t fix the weather.”

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].