A successful long-term experiment with live hogs indicates Nebraska scientists may be another step closer to achieving a safe, long-lasting and potentially universal vaccine against swine flu.

The results are not only important to the pork industry, they hold significant implications for human health. That’s because pigs act as “mixing vessels,” where various swine and bird influenza strains can reconfigure and become transmissible to humans. In fact, the 2009 swine flu pandemic, involving a variant of the H1N1 strain. first emerged in swine before infecting about a fourth of the global population in its first year, causing nearly 12,500 deaths in the United States and perhaps as many as 575,000 worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Considering the significant role swine play in the evolution and transmission of potential pandemic strains of influenza and the substantial economic impact of swine flu viruses, it is imperative that efforts be made toward the development of more effective vaccination strategies in vulnerable pig populations,” said Erika Petro-Turnquist, a doctoral student and lead author of the study recently published in Frontiers in Immunology.

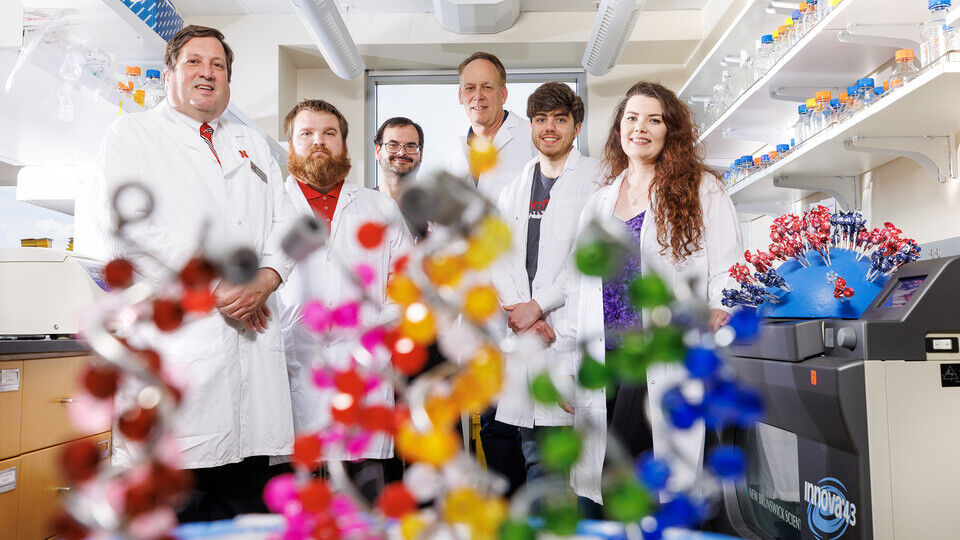

Petro-Turnquist is advised by Eric Weaver, associate professor and director of the Nebraska Center for Virology. Weaver’s laboratory is spearheading an effort that uses Epigraph, a data-based computer technique co-developed by Bette Korber and James Theiler of Los Alamos National Laboratory, to create a more broad-based vaccine against influenza, which is notoriously difficult to prevent because it mutates rapidly.

Pork producers currently try to manage swine flu by using commercially available vaccines derived from whole inactivated viruses and weakened live viruses. As of 2008, about half of the vaccines in use in the United States were custom-made for specific herds—an expensive, time-consuming and not very effective strategy because of the rapidity with which swine influenza evolves.

The Epigraph algorithm enables scientists to analyze countless amino acid sequences among hundreds of flu virus variants to create a vaccine “cocktail” of the three most common epitopes—the bits of viral protein that spark the immune system’s response. It could be a pathway to a universal flu vaccine, which the National Institutes of Health defines as a vaccine that is at least 75% effective, protects against multiple types of influenza viruses for at least one year and is suitable for all age groups.

“The first epitope looks like a normal influenza vaccine gene, the second one looks a little weird and third is more rare,” Weaver said. “We’re reversing the evolution and bringing these sequences that the immune system recognizes as pathogens back together. We’re computationally re-linking them and that’s where the power of this vaccine is coming from, that it provides such good protections against such a wide array of viruses.”

In another strategy to heighten effectiveness, the vaccine is delivered via adenovirus, a common virus that causes cold-like symptoms. Its use as a vector triggers additional immune response by mimicking a natural viral infection.

Two years ago, Weaver’s team published initial results in the journal Nature Communications, based on tests in mice and pigs. Those findings indicated the Epigraph-developed vaccine yielded immune response signatures and physiological protection against a much wider variety of strains than a widely used commercial vaccine and wildtype flu strains.

The follow-up study is apparently the first longitudinal study comparing the onset and duration of an adenovirus-vectored vaccine with that of a whole inactive virus vaccine. Petro-Turnquist and Weaver, along with Matthew Pekarek, Nicholas Jeanjaquet and Hiep Vu of the Department of Animal Science, Cedric Wooledge of the Office of Research and Economic Development and David Steffen of the Nebraska Veterinary Diagnostic Center, observed 15 Yorkshire cross-bred female pigs over a period of about six months, the typical lifespan of a market hog.

One group of five received the Epigraph vaccine, a second group of five received a commercial whole inactive virus vaccine, and a third group of five received a saline solution to serve as the control group. The pigs received their initial vaccination at three weeks of age and a booster shot three weeks later. Their antibody levels and T-cell responses were measured weekly for the first month and every 30 days thereafter. At six months of age, they were exposed to a strain of swine flu divergent from those directly represented in the vaccine.

The pigs that received the Epigraph vaccine showed more rapid and long-lasting antibody and T-cell responses to the vaccines. After exposure to the swine flu virus, the Epigraph-vaccinated hogs showed significantly better protection against the disease—less viral shedding, fewer symptoms of infection and stronger immune system responses.

“Those pigs weighed about five pounds when we vaccinated them and by the end of the study, six months later, they were over 400 pounds,” Weaver said. “It’s kind of amazing that this vaccine would maintain itself over that rate of growth. It continues to expand as the animal grows.”

Weaver’s team continues to pursue the research, with next steps including larger studies and possibly a commercial partnership to bring the vaccine to market.

“The more times we do these studies, the more confident we get that this vaccine will be successful in the field,” Weaver said.