Meeting the needs of consumers is a task that many farmers take seriously. Many have spent time at the kitchen table or coffee shop wondering if it is time for them to dip their toe into the direct consumer pond.

Advice is aplenty but here are two success stories—Wholly Cow Market and Leafy Green Farms—where owners spoke candidly about the mindset necessary to make a change.

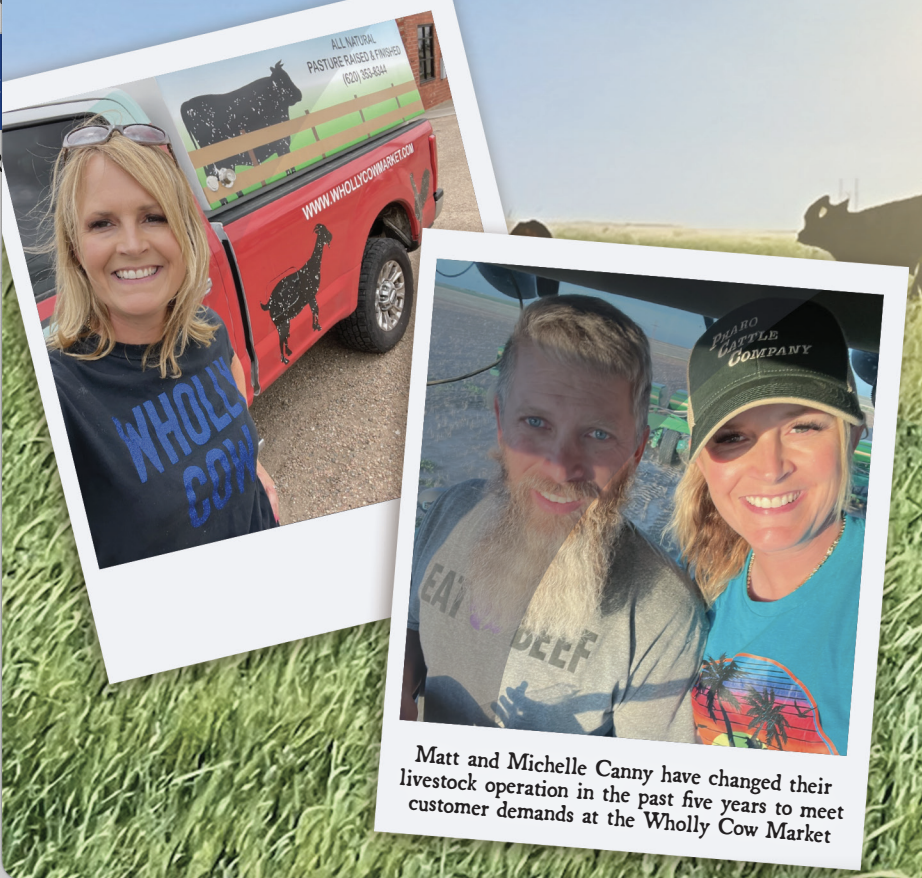

Michelle Canny, Johnson City, Kansas, and her husband, Matt, own Wholly Cow Market. Five years ago, Canny’s farm faced difficult financial stress. A prolonged drought hurt their corn and sorghum crops and her husband faced the process of culling cattle. Matt is a fifth-generation farmer and rancher and he and his wife decided they needed a new approach. Their research led them to a grass-fed operation. They have rangeland and their decision was to graze the cattle longer instead of putting them in a traditional feedlot situation.

Instead of selling the animal for $1,000, they could hold it, Michelle said. They developed their own strategy, and the result was that various cuts could net them as much as $4,000 a head. The first year Matt started with 11 head and they sold them all in a year’s time. They contracted with Percival Packing, Scott City, a custom processor that is U.S. Department of Agriculture certified.

Michelle said her husband didn’t expect a big demand for grass-fed beef.

“We had to step outside our comfort zone and our own biases and look at numbers without emotion or to be attached to the mindset of we’ve always done it this way,” she said. “We started putting a pencil to it and then tested the market to see if there was a demand. We found there was a demand. It was fun because our customers actually educated us on the benefits.”

Listening to customers works because they keep the Canny name in front of future consumers, she said.

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, they found that consumers continued to want their grass-fed beef. As their business grew, they had an opportunity to purchase a former pharmacy and in November 2021 they opened a restaurant that provided another outlet for their products.

Michelle believes strongly in building relationships and networks.

“Collaboration has been a big part of our success. we feature a lot of Kansas products and those relationships build,” she said.

She strongly endorses the From the Land of Kansas program.

The Cannys also networked with the state. A $75,000 grant allowed them to buy a specialized vehicle to deliver frozen products to Topeka, Wichita, Manhattan, Kansas City, Colorado Springs and Denver.

Her advice to those who are looking at specialty opportunities is to have an open mind.

“In our case it was based on dire straits, but we weren’t ready to throw in the towel,” Michelle said. “I think a lot of it is just humbling yourself. This is not the direction we thought we wanted to go at first or the direction other people expected us to go but this was what we needed to do.”

Her advice to specialty entrepreneurs is to do their own research, reflect on what they have learned, be comfortable with their decision, and be willing to take a risk.

“Let’s face it farming people and those who are involved in agriculture face risk every day. So why not capitalize on a risk that could bring you a premium for your product? When we first started Matt made the comment ‘I’ve always been a price taker.’”

The Canny’s message is that producers who are willing to take the risk have an opportunity to capitalize on the quality of their product and there are consumers who are willing to pay for the product.

Leafy Green Farms

Leafy Green Farms, Pittsburg, Kansas, is a veteran-owned and operated vertical, indoor, hydroponic farm and is the first of its kind in Kansas. The operation specializes in growing leafy greens including lettuce, arugula, herbs, Swiss chard, kale, and more. Owner and founder Brad Fourby moved to Kansas in 2020 in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic and started a farm in June 2021.

Leafy Green Farms Director of Communications Leslie Montee said Kansas is a highly agricultural state and 87.5% of the 46.76 million acres is devoted to traditional farm practices. Kansas and other Midwestern states do not have ideal weather to grow nutrient dense greens like kale, chard and lettuce varieties in a conventional process, which means innovation is needed to open a new opportunity.

“On average, fresh produce travels 1,500 miles before it ever hits your plate,” Fourby said. “By that time, it’s compromised. It’s nowhere near as good as it could be if you were able to harvest it and eat it within the hour, which is what we do here. I always say people eat with their eyes, and if you see a bright plate of vibrant greens, you’re more likely to eat that then you would say, a 10-day old plate of iceberg.”

Montee said the educational effort helps because fresh food helps meet nutritional needs.

“If we deliver kale to a food pantry, we want the consumers to know that not only does it taste good, one cup of it provides 684% of the daily vitamin K needed for an average adult. Vitamin K promotes healthy bones and bone tissue.”

Fourby said Leafy Green Farms is a model for vertical farming and can translate into success for a traditional farm and ranch operation. Farmers travel to see the facility, mostly in their off season or when their schedule allows, and they note the differences, including a constant temperature at 64 degrees Fahrenheit.

“We are still farming 365 days a year despite any outside factors,” he said. “We see their wheels start to turn and they begin thinking, ‘Hey I could easily do something like this during our off season, as a supplemental income.’”

Montee said traditional farmers are her favorite groups to host because they offer valuable perspective and ask good questions.

With a 365-day growing operation, Fourby says there are no off days. Labor is required for 20 hours a week, per farm.

“We don’t have any trouble off-loading our harvests either,” he said. “We have had multiple restaurants come in and say, ‘Hey, I’ll take it all’ but that’s not what we’re aiming for. We want to raise the nutritional needle in Kansas and beyond so we’re starting with the most vulnerable populations.”

It has been gratifying to see the results from the operation as Fourby said every day is a success and it gets important food products to people who need it. Montee said if people want to have a tour or learn more about the operation, they can contact her at 417-349-3478 or [email protected].

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].

Be realistic, start small and be persistent, experts say

By Dave Bergmeier

Developing a plan to diversify an operation will take time. If a farmer or rancher is looking to enter into a specialized market he or she needs to take an assessment of resources.

Tori Laird, an economist with the Kansas Department of Agriculture, said traditional agriculture is a volume-based industry. In grain production quantity of bushels keys profitability, she said. Specialty crops require a stress on quality. They may require additional labor and that is not always going to be available at harvest time. If a crop requires hand-picking that may not be readily available in many rural communities.

However, that should not deter producers from seeking opportunities, Laird said. A Colorado farmer was able to gain a niche with buckwheat using his existing equipment. The farmer found a processor who was seeking a special type of buckwheat and the producer was able to fill that need.

Laird’s advice for farmers is to start small and build on opportunities by paying close attention to marketing. They may need to work with local elevators and merchandisers to find places to store a crop if they are limited on their on-farm storage. She said that may not be feasible at first.

“You will have to get out of your comfort zone,” Laird said.

Kansas farmers have always been innovators and many years ago the state was a major supplier of potatoes, grapes and sugar beets but growers left for economic reasons.

She also sees sunflowers as a crop that could re-establish itself if a processing system was available. Sunflowers dovetail nicely with farm operations because they mesh with existing equipment.

There is a demand for sunflowers whether it is for human consumption or birdseed, Laird said.

Regardless of the opportunity, the economist said it does require perseverance.

“You have to have moxie and not be averse to risk,” she said. “Start small, educate yourself and her realistic.”

Laird said a specialty crop can be grown on a small piece of land that is part of the overall traditional operation. She suggests starting with a local Extension office and cooperative research service centers because they can connect a producer with a researcher.

Russell Plaschka, agricultural marketing director with the Kansas Department of Agriculture, says it all starts with good planning.

As an example, the most visible specialty opportunity in rural communities is at farmers markets that provide a venue to sell fresh produce. However, the demand for the products is year around and storage is problematic.

Consumers in rural communities without a grocery store may actually provide valuable feedback to help an entrepreneur, he said. The Kansas Department of Agriculture has been working with the United States Department of Agriculture to help secure monies that can help reduce risk for entrepreneurs, he said.

Michelle Canny, with Wholly Cow Market, Johnson City, Kansas, also believes in developing connections. “Don’t try to do it alone. Find people who are successful in what you’re looking at doing and talk to them and ask many questions.”

Successful entrepreneurs are willing to share advice. She also said do not shy away from local resources and, in her case, she found the Kansas Department of Agriculture had resources to share.