Lesser prairie-chicken needs landowners

Lesser prairie-chickens could be headed to the Endangered Species Act lists proposing two population segment boundaries in the High Plains region.

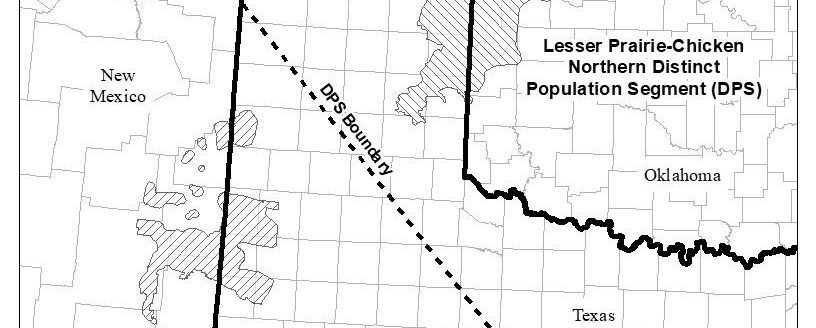

The boundaries include a southern district for eastern New Mexico and across the southwest Texas Panhandle where the birds could be considered as endangered and there is a danger of extinction. The northern region, which includes southeastern Colorado, south-central to southwest Kansas, western Oklahoma and northeast Texas Panhandle would be classified as threatened. Birds in this region are considered to become endangered in the foreseeable future.

A decision is not final as the regulators at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is seeking public comments and public hearings are scheduled for July 8 and 14.

This, of course, is not the first time the bird has been a headliner. U.S. Sen. Jerry Moran, R-KS, has provided a timeline since 2013 of more than a dozen actions the U.S. Senate, which also included former Sen. Pat Roberts, chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee, took to provide sound policy. There need to be common sense plans for making sure the species can survive and thrive and allow farmers and ranchers to continue to do their job as they have long demonstrated they are up to the task of being stewards of the land. They are joined now by Kansas Republicans Sen. Roger Marshall, a member of the Senate Ag Committee, and Rep. Tracey Mann, a member of the House Agriculture Committee, in asking regulators to take into account what landowners are doing before issuing restrictions that could derail important economic activity that not only includes agriculture but also oil and gas and renewable energy projects.

Regional wildlife executives have applauded the voluntary work of landowners to preserve the habitat.

An aerial survey of the lesser prairie-chicken numbers, over an extended, multi-year period, average 27,384 birds. The bird counts were estimated at about 34,400 in October 2020 in a report compiled by the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

Many of those who have observed the process have recognized that when the bird numbers were lowest it came at a time when drought was severe. When moisture is plentiful, the habitat springs to life. The lesser prairie-chicken benefits as does farmers and ranchers who depend on the land for supporting cattle and other interests.

The best opportunity for the lesser prairie-chicken to succeed is to have plentiful and available acreage for its habitat to flourish. The incentive is strong enough that investment firms who share an interest in preserving the habitat, such as Wayne Walker, principal of the Common Ground Capital, have rightfully concluded the bird requires large, intact strongholds, and who can do that better than those who already have a vested interest.

“Our ranchers can provide strategic, accountable conservation gains that includes the last of the best habitat for these birds,” Walker recently told High Plains Journal.

A final decision on the bird won’t be known for awhile but many people will be watching.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].