‘It’s not fun to watch things die’

Nature copped a surly disposition at the dawn of spring 2023, sentencing producers in mid America to a bipolar type of growing season.

Drought swiped much of the bounty from wheat harvest, which gave way to hope-affirming rainfall across much of the Great Plains as the second crop season ensued.

But just as food growers were beginning to anticipate paybacks for the approaching fall harvest, hellish heat swooped in and quickly crusted yield goals.

Volatile conditions continued.

After a relatively brief, but life-giving downpour in mid-July in and around Salina, Kansas, passersby were gifted a rainbow. As clouds parted in the western sky, an amber beam of sunlight found its way to the Archer Daniels Midland grain terminal near the city, as the arch of color floated by.

Moisture provided relief that day but the picture proved to be fool’s gold.

“I had the best dryland corn I’d ever had,” said Justin Knopf, a farmer in southeastern Saline County. “The sorghum and soybeans looked better than they had in quite a few years. I was very cautiously optimistic about having good yields this fall and getting back to an above-average harvest.

“Oh, how fast things can change here in Kansas.”

By the end of July, daily high temperatures boiled to as high as 108 degrees Fahrenheit in Salina, 107 in Russell, Kansas, according to the National Weather Service in Wichita. Rains came to a halt, Knopf said, landing a major blow to this fall’s harvest returns. Corn appeared to be losing quality.

“The tissue has died from the ground level to the ear leaf, and some places higher,” Knopf said Aug. 2. “This is a significant reduction to your yield potential. All summer long, we haven’t had big rains to fill up our water soil profile moisture. We had no water reserves under the plants for them to be able to cool themselves under this heat.”

Hopes were dashed in roughly 10 days, said Jay Wisbey, agricultural Extension agent in Saline and Ottawa counties.

“It really crashed. We call it a flash drought. We weren’t sitting on much moisture,” he said. “Some places have caught little popup showers, allowing it to hang on. Other places haven’t gotten it. Some of the poor guys who actually got rain, got it with hail and some fields were wiped out around Ada, some at Tescott. The corn was looking good. Then they got a storm. It took all the leaves, and now it has to be chopped for ensilage. It’s not fun to watch things die.”

Conditions still range by field and planting times.

“Early planted corn is taking it pretty hard with the heat. Late planted corn, like in June, still has a chance, if it would go ahead and rain,” Wisbey said.

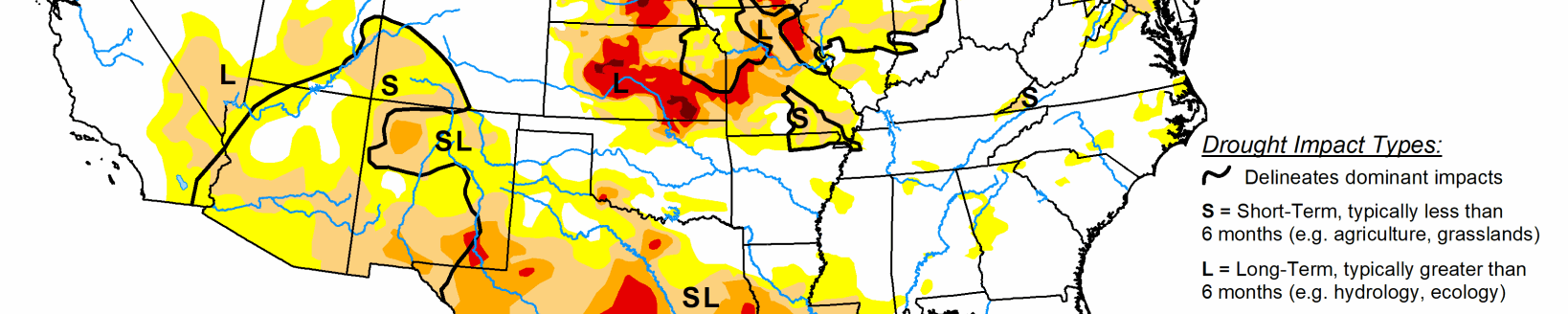

As of July 25, the National Weather Service reported, central Kansas was hurting the most from drought conditions, while six of the seven western-most counties in the state were showing no threat on the U.S. Drought Monitor map.

“There were areas with absolutely no precipitation and others just got inundated (with rain),” said Mark Rude, executive director of Southwest Kansas Groundwater Management District No. 3.

He pointed to a July storm that bathed areas north of Garden City with 3 inches of rain, perhaps more to the south.

There were flash flood warnings, he said, thanks to “significant rains on top of wet conditions.”

When blast-furnace conditions came later in July, crops could pull from what soaked into the soil.

“Guys are managing their moisture bank,” Rude said.

After driving to North Dakota in early August, he reported seeing some hail damage in areas, “but there are some beautiful dry-land crops.”

Farmer Jerry McReynolds has been staring at some thirsty crops in eastern Rooks and western Osborne counties.

“It’s been a dry booger. It just won’t give up.” he said. “We’ve gotten a little bit of rain—20 hundredths, 30 hundredths—just enough to barely keep us going until this hot spell hit. Now it’s just cookin’ us.”

McReynolds reported “just a sprinkle” from an Aug. 1 storm cloud. “We have no reserves—the milo, the soybeans, the corn. Cattle feed and the grass are hurting badly.”

He’s been swathing Conservation Reserve Program grass to store some feed for the winter. The woes have collected on the heels of a wheat harvest that turned in yields from less than 10 to 30 bushels to the acre—a dismal 22-bushel average—all thanks to the dusty landscape. There was enough moisture for the crop to emerge last September, but nothing significant until this past June.

“We’re not against rain. We’re all for it,” McReynolds said. “We just can’t seem to get any of it.”

There is no solace in the irony that overall, conditions in Kansas haven’t been that bad this year, said Randy Picking, a self-described “weather geek” and reporter for KINA and other radio stations in north central Kansas.

Temperatures in July were 0.3 degrees below average, he said, with a median high in the range of 92.5 degrees.

“Except for the last 10 days, it’s been a very mild summer so far,” he said Aug. 2.

Considering the reported transition from a La Nina to an El Nino weather pattern, Picking wouldn’t be surprised by an early winter.

“We could have frost by the end of September and snow in mid- to late-October. I just have a feeling,” he said. “We’ve been fortunate so far.”

Below average temperatures were expected through mid-August, Picking added, and a chance for above-average precipitation.

Tim Unruh can be reached at [email protected].