The evolution of the wheat industry over the past 75 years

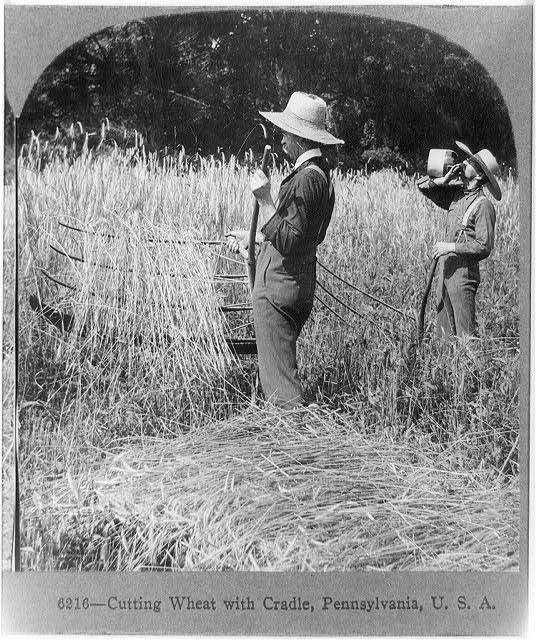

Imagine gazing out across a wheat field in 1949. It would present some obvious differences from the fields that dot the High Plains today. Kansas State University wheat breeder Allan Fritz said the most noticeable difference would be the height of the wheat 75 years ago, as that was prior to the introduction of semi-dwarf wheat. He said much of the wheat fields in 1949 would look like Turkey Red, a heritage grain that arrived in the United States in the early 1870s and has remained a foundation of today’s wheat breeding.

The tillage systems would have been all conventional systems, and Fritz noted that moldboard plowing was extremely popular at the time. Fertility application is another aspect of farming that has evolved immensely. The wheat varieties planted 75 years ago—specifically Wichita, Kiowa, Ponca and Bison in Kansas—were taller and not strong enough to handle the more abundant and thus heavier grains produced by high fertility varieties bred later on.

“You really couldn’t push the fertility on those varieties,” Fritz said. “They were 4 1/2 to 5 feet tall. If you tried to push the fertility, you were going to be picking it up off the ground.”

What does the data indicate?

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service has collected data on every wheat crop since 1918, which gives a unique perspective into how the wheat industry has evolved over more than a century. Looking back at Kansas’ 1949 wheat crop, 16,244,000 acres were seeded and 14,279,000 acres were harvested. The yield per acre was 11 bushels, and total wheat production was 157,069,000 bushels. The weight per bushel was a record low of 54.9 pounds, and protein content was at a high at 12.3%. Additionally, the most planted varieties were Pawnee, Comanche, Wichita, Tenmarq and Triumph.

Skipping ahead to the 1990 crop, 12,400,000 acres of wheat were planted in Kansas, and 11,800,000 acres were harvested. The yield per acre was 40 bushels, and total wheat production was 472,000,000 bushels. Protein content averaged 12.2%, test weight 60.7 pounds per bushel and moisture 10.5%. The most planted varieties were Tam 107, Larned, AgriPro Thunderbird, Newton, AgriPro Victory and Pioneer 2157.

The 2023 crop was a tough one for many farmers due to drought and torrential rainfall around harvest. There were 8,100,000 planted acres and 5,750,000 harvested acres. Total production was 201,250,000 bushels with a yield of 35 bushels per acre. Protein content averaged 13% with a test weight of 60.6 pounds per bushel and a moisture content of 11.6%. SY Monument, Bob Dole, SY Wolverine, WB Grainfield and Winterhawk were the most planted varieties.

Year to year the weather conditions and other factors influence the acres harvested and yield. One trend easy to glean from this data is that planted acres in Kansas has declined over the years. Fritz said this is partly due to improvements of other crops, such as corn and soybeans, and not planting as much wheat after wheat. The acres are also much more productive than they were 75 years ago, allowing for increased efficiency and bushels per acre.

“We’ve lost some acres over the years as cropping systems have become more diverse, and I don’t think that is a bad thing,” Fritz said. “As a wheat breeder, I love seeing wheat in the field, but I think that diversity in the cropping system is good. We’ve seen the genetics of wheat evolve as well.”

Borlaug’s influence and the future of wheat

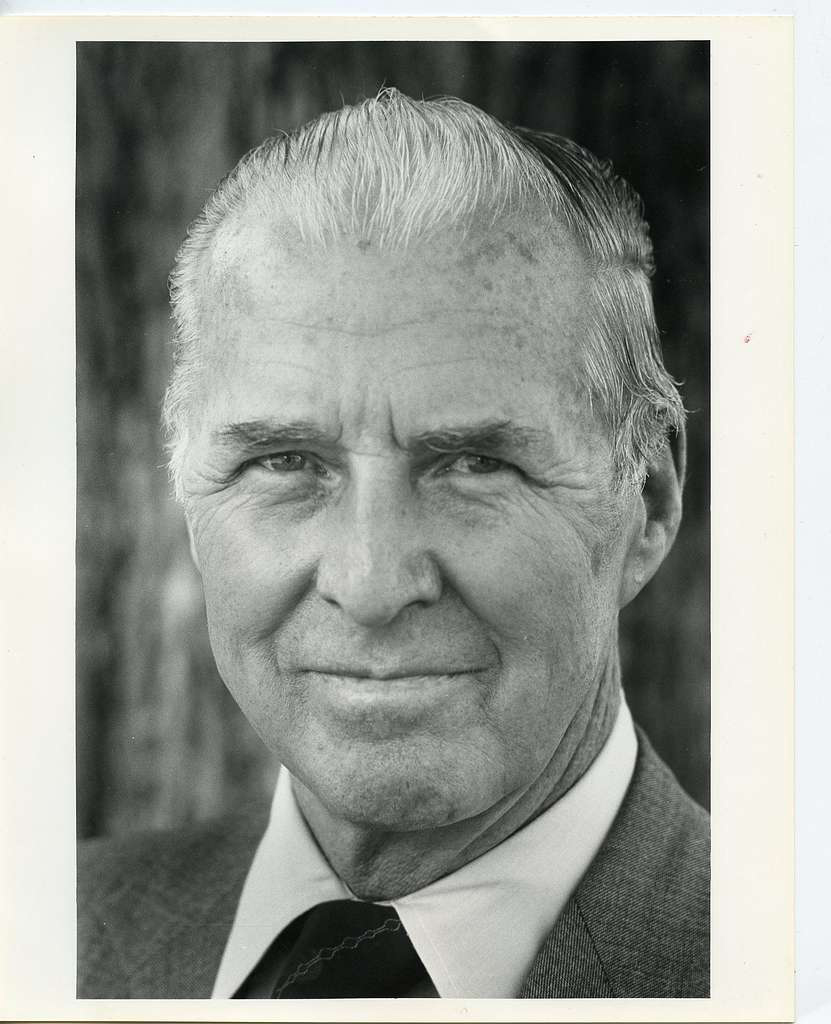

The topic of wheat improvements will always include Norman Borlaug. Known as “the father of the green revolution,” Borlaug developed semi-dwarf, high-yield, disease-resistant wheat varieties at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico in the 1960s and 70s. Fritz said Borlaug’s wheat breeding really hit the High Plains in the mid-1970s, when varieties started transitioning from standard height cultivars to semi-dwarf varieties.

“That really was all based on the work Borlaug had done at CIMMYT and the evolution of those genetics moving into the winter wheat region,” Fritz said. “That really changed how you can manage the wheat because we had fewer issues with lodging, and we really haven’t looked back from that point. His influence is almost incalculable.”

Fritz said the transition to semi-dwarfs enabled food security across the world and made wheat farmers much more productive. As for the future of wheat, Fritz sees opportunities for more improvements over the next 75 years.

“I think there is a lot to be excited about,” Fritz said. “Obviously, we’ve faced some profitability issues with wheat, but I think some of the things that we’re working toward, such as increasing the value of the crop in functional and nutritional quality and other attributes will add additional value.”

Fritz used the protein gluten processing plants at Phillipsburg and Russell, Kansas, as examples.

“If that is going to become a bigger part of our industry, how can we support them through the varieties that we develop?” he asked. “I also think there are opportunities in terms of how we design things to succeed in the environment, and I actually think that’s a real success story. Our varieties have tolerated the dry conditions far better than they used to. I think there’s also this element of needing to be prepared for whatever gets thrown at us and maintaining the diversity of the breeding program because you don’t know what disease or insects are going to come and put pressure on the plant.”

Even though breeders and producers are always looking toward the future, Fritz said it is important to remember where they started as well.

“Everything has been sequentially built from the initial landrace varieties,” he said. “It’s just been a process of continuous improvement and evolution of the wheat varieties over time. The breeders from 75 years ago are really critical to the success we have now. Everything is built on the shoulders of the past, and what we have today is not independent of what we had in 1949.”

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].