Preserving habitat for lesser prairie-chickens is crucial to their survival, and Wayne Walker believes one way to preserve habitat is to allow private investment so that farmers and ranchers have incentives to improve the land.

Walker, a principal with Common Ground Capital, LLC, was founded in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, but now operates out of Walker’s ranch in Wichita Falls, Texas, hopes that private interests will continue to work together toward that effort. One way is by the purchase of conservation bank credits, such as those Common Ground Capital offers.

The credits are certified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Walker spoke about the need to provide added incentives for farmers and ranchers during a recent tour that allowed journalists to see restoration and a live lekking so they could see how the bird can thrive. The photo above was taken during a recent lekking.

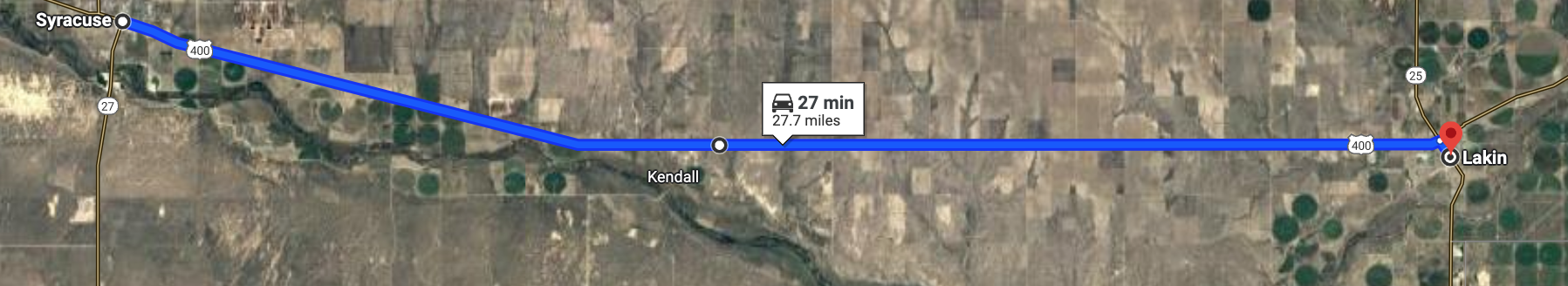

Common Ground Capital and Mark and Greg Gardiner, Angus ranchers in Ashland, Kansas, served as hosts as journalists from the High Plains Journal, Kansas Reflector and KOSU Radio/NPR from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, attended. Jackie Augustine, executive director of Audubon of Kansas, was on the tour to provide insight on lesser prairie-chickens. The April 23-24 tour occurred during the mating season on breeding ground areas of the ranch commonly called leks.

During the lekking season the males gather in slightly elevated prairie areas with sparse vegetation where they defend their territories and undertake colorful and spirited battles with other lesser prairie-chickens.

Building habitat

The key to increasing the bird’s population, which has been declining most years in the past decade, is to have habitat to support it. Landowners can use private conservation payments from those who buy conservation bank credits to improve their operations while preserving lesser prairie-chicken habitat.

Because federal regulators consider the lesser prairie-chicken to be an endangered species, those interested in the habitat preservation program must meet federal regulations. However, a case pending in federal court in Midland, Texas, is set to determine later this year whether lesser prairie-chickens continue to be covered by the Endangered Species Act.

Walker has spent many days in Ashland so he can help supervise and meet the requirements established by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the conservation credits. The credits are then made available to purchase by people or entities elsewhere in the country who receive the benefit of knowing they are doing their part to preserve habitat. The Gardiners have a 10-year partnership with Common Ground Capital.

The conservation credit program can be a good fit for farmers and ranchers as they tend to prefer voluntary incentives for habitat preservation to regulatory restrictions, and they face drought and at times down markets for farming and ranching in the habitat that best fits lesser prairie-chickens, he said.

The Gardiner operation has committed nearly 46,000 acres near the Kansas-Oklahoma border to maintaining their habitat.

“There’s enough acreage to have a (habitat) stronghold,” Walker said.

Conservation credits come with stipulations, he said, but added that he also has successfully worked with landowners who have oil and gas interests.

Gardiners’ work

The Gardiners will continue to stock cattle on their rangeland, earning a living from both cows and setting aside the habitat for the lesser prairie-chickens.

Improving rangeland, whether it is for cattle or other purposes, takes a long-term commitment, Walker said. The Gardiners wanted to remove salt cedar trees that suck water out of the prairie, and their restoration project includes eradicating the trees.

A roller chopper will be used to eradicate many salt cedars, but regular inspection and treatment are also necessary because if a salt cedar emerges, it can quickly grow and spread.

Without the salt cedars, native prairie grass will return, and invasive species are eliminated, he said. Eliminating the salt cedars also helps improve grazing lands to support cattle and removes a favored safe haven for prairie-chicken predators, including hawks. Lesser prairie-chickens already face intense pressure from predators, including coyotes and snakes that Augustine said eat the eggs they lay on the prairie.

The Gardiners made a commitment 10 years ago to remove the trees, but in 2017 they were like many landowners in the region where the Starbuck fire changed the landscape, and that gave a renewed hope to Walker about restoring the prairie.

“The fire cleared it up,” Walker said.

Birds have a legacy

In the 1880s, the prairie supported what biologists believe was millions of lesser prairie-chickens and buffalo. Bison during that time were slaughtered as part of the Indian wars. Farm and ranch activity changed the prairie. It also dramatically impacted the habitat of lesser prairie-chickens.

Augustine estimates there are now only about 18,000 lesser prairie-chickens in the western Kansas prairie.

Augustine said the survival rate for lesser prairie-chickens is about 50%, and at the lek she estimated half are yearlings, and half were born in 2023. About 15% of males will mate with about 85% of the females, which is why the lek experience is colorful.

Females lay about eight to 12 eggs, usually about one egg per day. It then takes about 23 days for the chicks to hatch. It takes about four to five weeks from the lek to get chicks, and those young birds can fly short distances about two weeks after they hatch. The young birds will consume grasshoppers and other insects that come from plants that attract them.

Walker, who has a farm and ranch background in Texas, enjoys watching the birds and marvels during the lekking season.

Dave Bergmeier can be reached at 620-227-1822 or [email protected].