Innovation has been a blessing in raising corn, from the husking hooks that were essential harvest tools a century ago to today’s pricey driverless tractors tugging grain carts.

The evolution of America’s most prolific crop followed a difficult journey through the first 70 years since the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service began publishing yield data. Average yields in those early years ranged from 20 to 30 bushels to the acre.

Science and mechanization gave it a boost in 1936. Breeding, hybridization, precision farming practices, mechanization, biotechnologies, information tech and farm management all played important roles, according to farmdocdaily.illinois.edu.

“My dad used to talk about husking corn in the ’20s and ’30s and tossing the ears in a trailer,” said Chris Short. He is pictured above, at right, with (from left) Tyler Ash, Matt Short and Zach Short.

His father, Robert R. Short, worked with Robert’s grandfather, John C. Short, who homesteaded the land in southern Saline County, Kansas, in the late 1880s and early 1890s. It’s where Chris Short still farms and lives today.

Earlier years

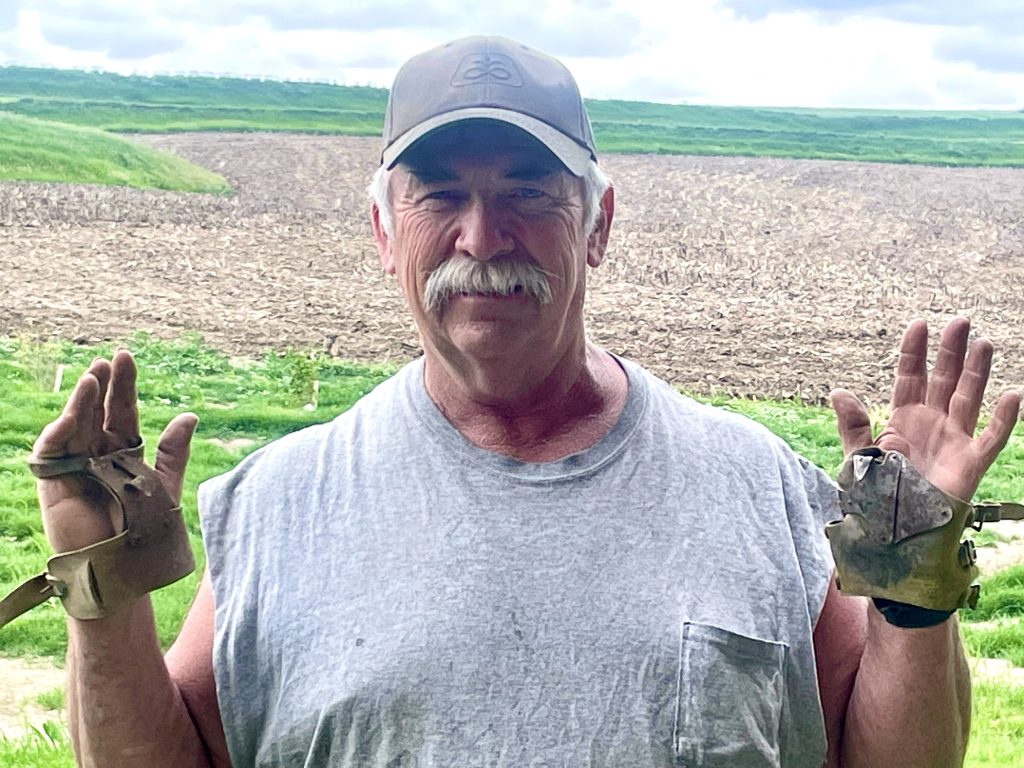

A couple of states to the northeast, in western Iowa, Mike Leonard’s grandfather, Ray Leonard, harvested by hand, when Mike’s father, Kenneth Leonard, was just a boy. They wore those specially made gloves affixed with hooks to make husking easier.

“When my dad started farming, things were becoming mechanical. He and my grandpa went from farming with horses to driving tractors in the ’30s and ’40s,” Mike Leonard said.

It was during that era when corn production began to boom to the point that the crop is planted on 90 million or more acres every year, primarily in the Corn Belt—a.k.a, the United States heartland—making it the most planted crop in this country.

The starch-filled grain that fattens livestock also nourishes humans around the world, pumping high demand for the plant and causing fortunes to be invested into improving it.

Important livestock feed

Roughly one-third of the domestic corn crop feeds livestock, providing the carbohydrates they need, while soybeans chip in the protein, according to the USDA in a 2019 publication.

Just more than one-third is used to make ethanol, a renewable fuel additive in gasoline, and the rest “is used for human food, beverages and industrial uses in the U.S. or exported to other countries for food or feed use.” Corn has hundreds of uses. It is used to make breakfast cereal, tortilla chips, grits, canned beer, soda, cooking oil and bio-degradable packing materials. It’s the key ingredient in life-saving medicines, including penicillin. “Corn gluten meal is used on flower beds to prevent weeds,” the USDA story reads.

The United States’ biggest corn customers are Mexico, South Korea, Japan and Colombia.

“Corn seems to be king nationally,” said Jay Wisbey, agricultural Extension agent for Saline and Ottawa counties, and himself a farmer in north-central Kansas. Corn is part of his family farm’s spring-planted repertoire.

“The crop has increased over the years. Dryland corn is the wildcard because its success depends more on rain (than irrigated varieties),” he said.

Yields have climbed steadily since 1936, and from 2016 to 2021, average yields ascended to 174 bushels to the acre, according to NASS, “a more than six-fold increase since the 1800s,” according to farmdocdaily.

Farmers Chris Short and Mike Leonard both have higher aspirations.

“We should always expect 200-bushel yields now, with 250 the ultimate,” said Zach Short, who farms with his father, Chris, and brother, Matt.

Big returns come from fields under irrigation from center pivot systems.

“We have hot spots in the fields that are over (200 to 250),” Matt said.

Water drives corn

Having access to water is vital.

“The (dryland) corners make 30-some bushels an acre on a drought year. On an average year, dryland can (yield) over 100 bushels an acre,” Zach Short said. “Mother Nature still has a big play in it.”

Mike Leonard remembers yields from 150 to 160 bushels to the acre in the 1980s when he started farming on his own in western Iowa.

“Ten years after, I began entering corn growers contests, and we started breaking 200. We were breaking records with our yields,” he said. “Now, we’re trying to get around 250. Our average is around 220.”

He credits improvements to corn hybrids and farming practices, including farming without tillage.

“We’re trying to keep our nutrients from leaving us. They call it variable rates of our inputs,” he said. “We go out and soil test a lot, and only put (inputs) where they’re needed.”

Kansas is far from the corn leader in yields, averaging 128 bushels to the acre from 2018 to 2023, said Doug Bounds, Kansas State statistician. Illinois averaged 201 bushels to the acre during that span, followed by Iowa, 196; Indiana, 189; and Nebraska, 183.

North-central Kansas bows to higher elevations in the state, said Chris Short. Salina is at 1,224 feet above sea level, while Garden City is at 2,828, and Syracuse, near the Colorado border, is 3,265.

“Yields are higher out west, thanks to their cool nights,” he said.

Corn enjoys advantages all over, Wisbey said.

“We’ve just got better hybrids and farming practices, everything from water conservation, no-till, better planters and fertility. A lot of things add up to those numbers,” he said. “Farming is a business, and corn, like every other commodity, competes for land. We try to plant what we feel is going to make us the most money in the end. That’s the goal. Sometimes it doesn’t work that way.”

Much of the focus is on improving corn.

“Universities do their research based on funding, as well as seed companies,” Wisbey said. “Corn and soybeans have the majority of acres, and there is going to be more money put into researching those crops.”

No-till and crop rotations are important, said Tyler Ash, who works for Chris Short, but farms for himself farther south, near Bridgeport, Kansas.

“If you can grow a decent corn crop, there is more profit, but seed and fertilizer costs are higher,” he said. “New hybrids have made a change in our yields, and picking corn is more enjoyable.”

Tim Unruh can be reached at [email protected].

Other contributors to corn boom

By Tim Unruh

Soil testing on a grid allows for fertilizing using variable rates, said Kansas grower Matt Short.

“We fertilize on both sides of the seed bed, overlay herbicides and put more fertilizer down, and then put down dry fertilizer,” he said. “All of those things have been helping increase our yield quite a bit.”

Zach Short mentioned hydraulic down force capabilities with planters that put the seed at an accurate depth. “We’re able to get a lot better stands with technology in the planters,” he said. “Corn’s all about even emergence.”

As a youngster, Chris Short recalled picking up dropped ears from the fields, but that’s no longer a big issue.

Yield robbing corn rust occasionally carries on the wind to their fields, Matt Short, said, requiring spraying fungicide.

“We do everything we can to where we’re not the limiting factor,” he said. “Out here, it’s about Mother Nature.”

Mike Leonard models a pair of corn husking gloves used to harvest the crop roughly a century ago in western Iowa, long before he was born. (Photo courtesy of Melissa Grimes.)

Mike Leonard can boast of 300-bushels an acre being recorded occasionally by combine yield monitors, and once logging 289 bushels an acre in one entire field.

He’s thankful to be farming in the Loess Hills in western Iowa and Missouri and eastern areas of Kansas and Nebraska, which sport deep topsoil.

“We’re fortunate to have that much dirt. We can maneuver that stuff around and still be able to grow crops on it,” Leonard said. “The really good dirt in Iowa is in the central part, but we have the good stuff in creeks. It doesn’t require as many nutrients. In the Loess Hills, you have to put a lot of food into it to grow the crop. Costs are higher, but the potential is great, depending on how you handle it.”

But farming has its share of “ups and downs,” he said, referring to 1954, when his dad’s corn yield was a mere 8 bushels to the acre.

“He had to sell off all the livestock, go to town and get a job,” Leonard said. Kenneth Leonard worked as an electrician and as a television repairman, installing TV antennas on windmills.

“It’s physically easier to farm now, but mentally, it’s very stressful,” said Mike Leonard, 63. “You have a lot of money invested out there, but it could fail because of Mother Nature.”

Decades ago, he said, work ethic got you through those difficult growing seasons.

“If you spent a lot of time and worked really hard, you succeeded. That’s not so much now,” Leonard said. “You can spend 18 hours a day, and it may not work out if you don’t make the right decisions. Everybody thinks it’s fun and games, but a lot of people don’t want this risk. Like I said, it’s very stressful.”

Tim Unruh can be reached at [email protected].