Panelists share about operations, challenges at Sorghum U/Wheat U

Despite their geographical differences, three farmer panelists found they had more than a few things in common during the producer panel at Sorghum U/Wheat U, Aug. 13, in Wichita, Kansas.

Panelists were Matt Durler, a Ford County, Kansas farmer, managing director of Climate Smart Sorghum and vice president of feed development for the ethanol technology company ICN; Keeff Felty, a fourth-generation farmer located near Altus, Oklahoma, and president of the National Association of Wheat Growers; and Chris Tanner, a Norton, Kansas farmer, vice president of the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers and vice chair of the NAWG domestic trade and policy committee. Adam York, CEO of the Kansas Grain Sorghum, moderated the panel.

Each producer discussed crop rotation and how wheat or sorghum fits into it. For Tanner, he first used a three-year rotation—fallow, wheat and sorghum. Today it is more of a corn, corn and wheat rotation.

“I do still do some fallow with landowners and things that allow for it,” he said. “But when I was younger, and first got started and kind of got in the habit where you chase the market to try and enhance profitability on your farm. But they say with age comes wisdom.”

For Tanner to maintain a disciplined operation going forward he needs to make sure the residue is working to maintain the moisture in the field. Weed control is helped by the wheat fallow and row crops, but leaving a heavy amount of wheat residue can help enhance yield too.

Felty includes cotton in his rotation as it’s one best suited for southwest Oklahoma.

“We’ve tried various other crops. Some of them work better than others,” he said. “In the past, I’ve grown sesame and it’s a really good rotation as far as helping with cutting the weeds and things on your wheat acres.”

Weeds are becoming increasingly hard to control and resistant to more products that farmers like Felty have in their arsenal.

“We try to evaluate the conditions and do the best we can with what we think the weather is going to be,” he said. “We aren’t planting cover crops on it now as part of some of the climate friendly procedures and processes, and occasionally we will go ahead and harvest equity and try to put another crop in some years, typically, that’s not something that we’re able to accomplish.”

Policy and federal farm program requirements can also hinder some of the crop rotation choices for producers, and for Durler, his family has found what works for them.

“We said that Dad became a no-tiller because I went to college and he didn’t have somebody to sit on that 846 anymore,” he said. “And I think there’s really a lot of truth to that, be honest with you.”

The Durlers have been predominately no-till for about 25 years and had a pretty strict crop rotation.

“No-tills allowed us to be a little more aggressive with that rotation and double up on wheat, and particularly places where we integrate the livestock, which we’ve tended to increase over time,” he said. “Wheat pasture, we hit and miss, but we’ll go back in our wheat stubble with some sorghum forages that allow us to either put some silage up or go ahead and graze that. So it works well with the livestock piece.”

While Durler grew up in Ford County near Wright, he spent the last several years in central Kansas. The differences in soil types, rainfall and crops show some stark differences.

“In Ford County, we’re kind of in the sweet spot for sorghum, and we’ve got decent soil. We can hold moisture pretty well in that 18- to 22-inch rainfall kind of area,” he said. “As I lived in central Kansas, the soil is a little less forgiving. You got to have the timely rains here (in central Kansas), whereas we got a full profile, we can pretty much raise the sorghum crop in Ford County. You can’t do that around here.”

Cover crops are definitely a buzzword in agriculture, and everybody wants to try it, Durler said.

“But moisture is our biggest limiting factor,” he said. “So we’re trying some of that behind sorghum. At this point, just trying to get some better ground cover ahead of that fallow period, we’re pretty bare, when we go back with the wheat.”

Durler also sees livestock as an integral part of the system.

“You got to stick with what works year in and year out, but then also to kind of mitigate some of that risk starting to work at annual forage and some of those insurance products that maybe are a little different than what we saw five and 10 years ago,” he said.

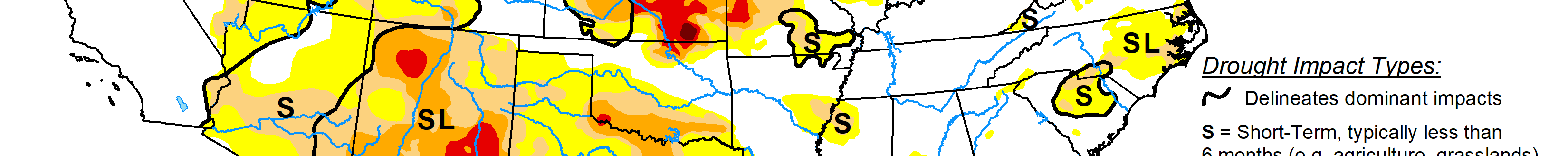

Felty said in the last five years, between the third year of drought and COVID, it’s been challenging. But it’s not all been bad.

“We did get some timely rains, and we had a good wheat harvest this year, so (we’ve) really been focusing more on better efficiencies and looking at better ways and timing of fertility,” he said. “And how to better approach managing inputs, especially with the current inflation and cost, and that’s really such a driving force now in what’s going on in agriculture is increased input costs.”

Upgrades

Felty has invested in some technologies and practices to better utilize inputs and have a more valuable and timely approach to their use.

Tanner agrees.

“It’s almost like the butterfly effect. It’s paying attention to what’s going on your fields and small things, and waiting to see how they respond,” he said. “I’ve run some soybeans in my farm in the last five years, where we had a hot, dry spring, and the crops that are behind that now, even with the residue mat later on, you can kind of see right to the line where they were at, because that residue was gone.”

Tanner has tried to be more attentive to the residue management and paying attention to how the combine spreads it in the field at harvest. Being more intentional about grazing and doing it responsibly is essential too.

“And biologicals, that seems to be the wild, wild west. That seems to be an evolutionary process,” he said. “You can have height where I’m at, variability in your soils, biologicals within a field and across the county and (I’ve) kind of been paying a lot more attention for that; and return on investment.”

Some practices may work, but their costs may be “so far out of line, it just doesn’t make sense to do so.”

“But biological residue management for me, going back to the cover crop thing that where I farm, we don’t have enough rainfall to make them work,” he said. “One thing we’ve kind of been doing, Kansas Wheat is trying to work with the policy, and idea that wheat should be listed as a harvestable cover crop, just due the fact that it’s kind of works in our arid regions.”

Takeaways

The panelists shared a couple key takeaways for the next generation in the room. Felty said there’s still a lot of new and exciting developments with many commodities—with a caveat.

“You have to find out what works best for you, talk to your neighbors, talk to your family. There’s a reason why things happen in your communities the way they do. Because they work,” he said. “There will be changes and there’s lots of information out there, and the best thing that you can do is figure out what will work for you, and just remember that because it worked this year doesn’t mean to work next year.”

There could be an early or late freeze, there could be hail or some other things that farmers don’t have control over.

“Take advantage of the opportunities that come along,” Felty said.

Tanner said Mother Nature is a “cruel, miserable, mean woman,” and try not to let the weather or environment influence them too much.

“Don’t mistake your view of yourself on your net worth. And some years, things don’t work out,” he said. “Obviously, if there’s young guys in this room, you’re paying attention and running and trying to enhance and grow yourself and stay on top of things. Continue to do that, continue to learn and take care of your soil, and that’ll take care of you.”

Durler agreed and said many producers are walking into what looks like probably three years of pretty tough farm income. Accept the challenge and look for incremental ways to make money.

“Hope is not a strategy,” Durler said. “We tend to all get better when the times are the toughest, because you have to mine the pennies to make it work. We get very lazy when we have $7 corn. It’s just reality.”

Durler credits his involvement with the commodity and trade organizations, to helping him stay engaged, and believes how important it is for producers to get involved.

“And while there is tremendous differences in agriculture regionally, there’s a lot of things that people are trying that network can be worth a lot to you,” Durler said. “Those kinds of commitments, building out your network with people that you can trust to try things goes as far as anything.”

Perspective is important for producers, especially one that is out of your backyard.

“Try things. Don’t be afraid to fail. You can’t risk the farm on it, but you have to push the envelope,” Durler said. “And then I really do believe going forward, to look at ways to extend the control area output if you don’t have control of how you’re going to tell your story, and how you’re going to get paid for the things that you’re willing to do.”

Kylene Scott can be reached at 620-227-1804 or [email protected].