If you’re a row crop producer, you’ve probably sensed the economic headwinds flowing your way. Many producers are tightening their belts heading into 2025 and having more difficult discussions with their lenders.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s latest farm income forecast is better than first projected in February, but still the agency expects net farm income will fall by close to 7% from 2023.

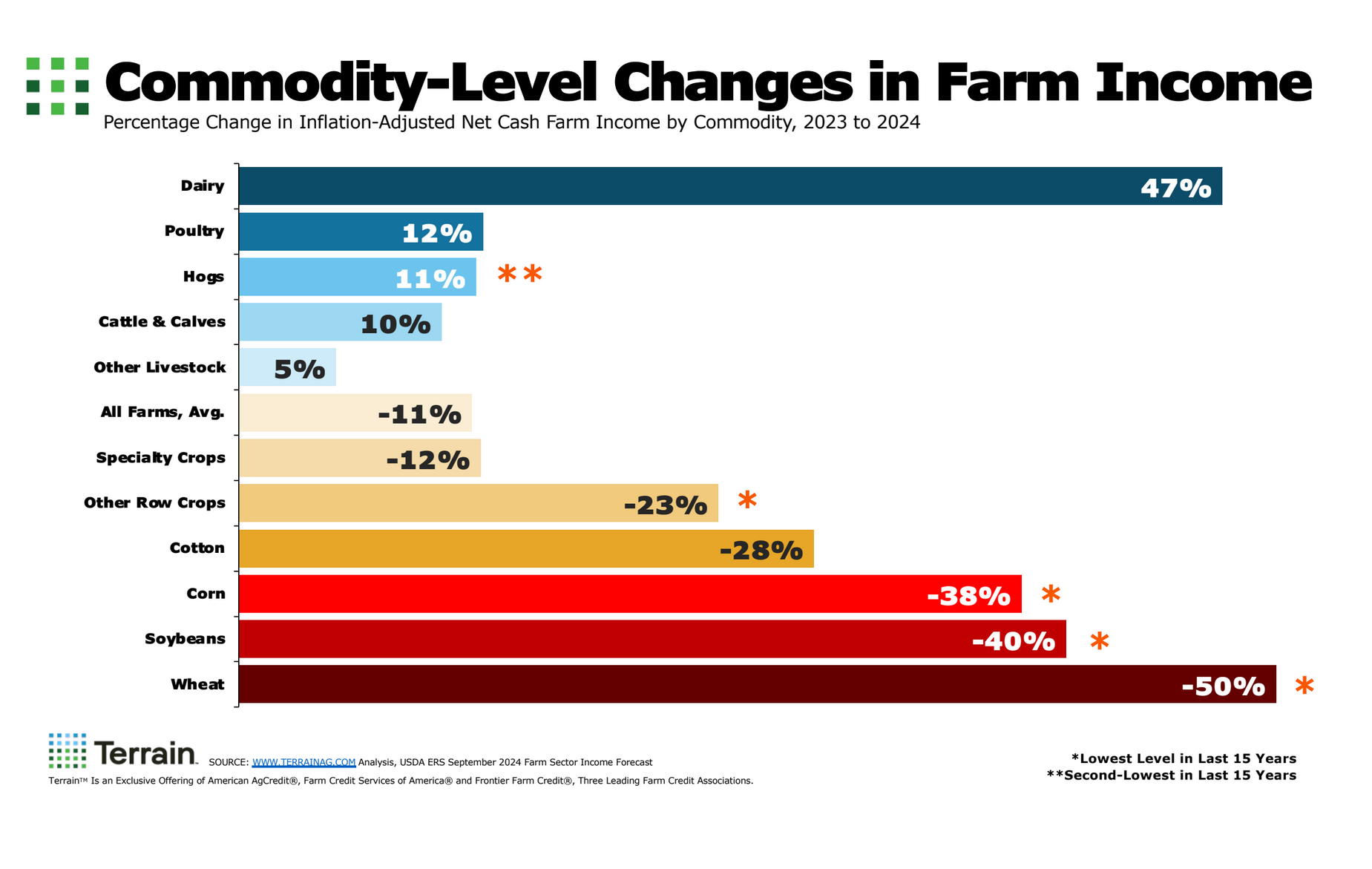

The new forecast reflects wide variations in earnings by sector. Stronger than previously estimated profits in the cattle, dairy and egg sectors are expected to partially offset price declines that are hammering many row crop producers this year, according to the latest farm income outlook from USDA’s Economic Research Service, released in early September.

Speaking at the Ag Outlook Forum in Kansas City recently, USDA Chief Economist Seth Meyer said net farm income for 2024 is now estimated at $140 billion, a decrease of $10.2 billion, or 6.8%, from 2023, when adjusted for inflation. Despite the drop, net farm income would still be 15.2% above the 20-year average.

Net cash farm income, which more closely tracks farmers’ cash flow, is forecast at $154.2 billion. When adjusted for inflation, that would be a decline of 9.6%, or $16.3 billion, from 2023, and 6.2% above the 20-year average.

Net cash farm income is based on cash receipts from farming, plus government payments and other farm-related income, minus cash expenses. Net farm income also factors in depreciation and changes in inventory values.

“If you look at what folks were making a couple years ago to today, I mean, this is among the sharpest declines in the farm economy that we’ve ever seen,” said John Newton, executive head of Terrain, at the Outlook Forum, who provided the above chart.

“When you look below the aggregate net farm income measure, you start to see something different at the commodity level,” he added. “Net cash farm income for wheat producers is expected to be down 50%; soybeans are looking at a 40% decline in overall profitability; for corn, a 38% decline; for cotton, a 28% decline. Other crops, including rice, are looking at a greater than 20% decline in their farm profitability year over year.”

He said there is a lot of uncertainty in farm country, citing the amount of grain that farmers are keeping in storage, hoping that prices improve.

“That’s risky given the cost of credit, the cost of storage,” he said.

Newton said the price declines underscore the need for a new farm bill. Prices for major crops, other than possibly cotton, remain above the levels that would trigger payments under the Price Loss Coverage. Some farmers could see payments under the Agriculture Risk Coverage, but not if yields are strong, he noted. ARC triggers payments to farmers when average revenue in their county falls below a five-year average. Yields as well as market prices factor into whether growers get ARC payments.

That’s one reason commodity groups joined forces with lenders on Capitol Hill recently to visit with members of Congress and discuss the red ink that’s starting to show on their balance sheets.

Next year is likely to be challenging for farmers as well, he said. “We know based on the USDA cost of production forecast for 2025, their expected input costs remain elevated, and yet commodity prices have fallen,” he said.

Meyer agreed that some input costs, like fertilizer, remain elevated and could remain “sticky” at the higher levels. For example, with “N, P and K, we’re still above where we were four years ago. Labor’s been a continued issue, and you see the labor costs continue to rise.”

One bright spot is that the Federal Reserve recently announced a drop in its benchmark interest rate by a half percentage point, to a range of 4.75% to 5%. That’s the first time in the last four years that the cost of borrowing has dropped.

“I think it’s important during periods where margins are pretty tight and you’re borrowing for operating loans. So, that that’s a welcome change,” Meyer added.

During these tougher economic times, it’s also important for both lenders and regulators to be proactive, said Jackson Takach, the chief economist and head of strategy, research, and analytics at Farmer Mac.

“Regulators need to make sure that banking institutions have access to all the capital that they need, all the support that they need, and all the understanding that they need to continue to be able to lend capital in a more challenging environment,” he said.

Editor’s note: Sara Wyant is publisher of Agri-Pulse Communications, Inc., www.Agri-Pulse.com.