For months, members of the International Longshoremen’s Association have raised the threat of a strike amid disagreements with the United States Maritime Alliance, an association representing container carriers, marine terminal operators and port associations stretching from Boston to Houston.

Negotiations appear to be stalled over wage increases, benefits and the future use of automation. Just a stroke after midnight on Oct. 1, ILA members fulfilled on their threat and began forming picket lines at East and Gulf ports.

“We are prepared to fight as long as necessary, to stay out on strike for whatever period of time it takes to get our wages and protections against automation our ILA members deserve,” ILA president Harold Daggett said in a statement the organization posted on its Facebook page.

Union leaders say they’re dissatisfied with USMX’s latest offer of wage increases, employer retirement contributions and higher starting salaries. Daggett has called for royalties on containers, health care improvements and complete bans on automation and semi-automation.

Shortly before the workers went on strike, USMX showed some flexibility on its previous terms, announcing it would consider a 50% wage increase along with a commitment to triple employer contributions to employee retirement plans and stronger health care options, according to a release.

Despite ILA’s requests for complete bans on automation and semi-automation, USMX has so far only offered a commitment to halt the use of fully automated terminals. It still wants to allow some semi-automated equipment if both parties can agree on appropriate workforce protections and staffing levels.

The union rejected the offer Sept. 30, saying it “fell short of what ILA rank-and-file members are demanding in wages and protections against automation,” according to a release.

The ports of Virginia, Houston, Savannah, New York, and New Jersey had all halted container-related operations by the end of the day on Monday. In addition, two railroads—Norfolk Southern and CSX—have temporarily embargoed shipments to some East Coast ports.

Containers vs. bulk

The strike gives life to agricultural shippers’ fears of a disruption that could hinder the flow of containerized agricultural product shipments to other countries at a critical time when farmers are harvesting. Approximately 40% of U.S. containerized agricultural exports move through East and Gulf Coast ports, agricultural groups told President Joe Biden in a letter last week.

“[If] containers are the majority of your export business and the majority of that’s going through the East Coast, you’re now in a really tough situation,” National Grain and Feed Association President Mike Seyfert told Agri-Pulse. “Your supply chain’s been shut down—the supply chain you built your operation around—and now you’ve got to try and find an alternative market. That’s not always an easy thing to turn on a dime to do.”

For Midwestern corn and soybean producers, the good news is that most- but not all- of your commodities are moved in bulk, rather than containers.

Last year, 54 million metric tons of U.S. soybeans were exported by bulk and the Mississippi Gulf region (near New Orleans) is the No. 1 export region for soybeans. In 2023, 27 million metric tons of soybeans were exported from the region—all of which occurred via bulk.

However, 5.8 million metric tons of soybeans were exported via containers. Of that 5.8 million, approximately half of that was exported via the East and Gulf coasts. The other half was primarily exported via Los Angeles/Long Beach and other West Coast ports, according to Soy Transportation Coalition Executive Director Mike Steenhoek.

“Therefore, we’re looking at approximately 5 to 6% of total soybean exports that will be impacted by a strike on the East and Gulf coasts,” he noted in an email.

But grain growers are also worried about their livestock customers and the detrimental impact on meat and poultry exports.

“So many of the soybeans grown in the U.S. are ultimately fed to livestock for both the domestic and export markets. You cannot harm meat and poultry exports without harming soybean farmers,” Steenhoek said.

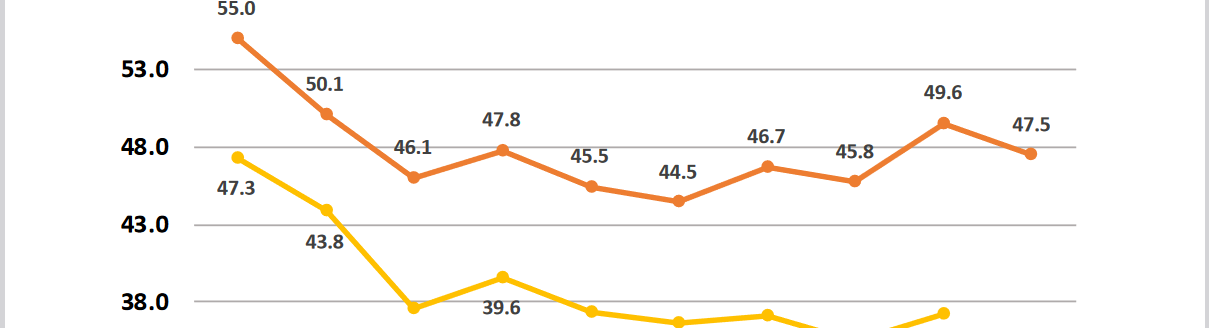

Poultry was the largest U.S. agricultural export sent by container through 14 major East and Gulf Coast ports, according to an Agri-Pulse analysis of USDA data.

American Farm Bureau Federation economist Daniel Munch noted in a recent blog post that East Coast ports manage 78% of waterborne poultry exports.

East and Gulf Coast ports are also important junctions for exports of raw cotton, animal feed, soybeans and meats and imports of bananas, beverages, grocery items, fruit and wine. Munch estimated that the strike could have a $1.4 billion impact on containerized agricultural exports and imports for each week it goes on.

Will Biden step in?

Agricultural groups previously urged the Biden administration to force both parties to return to the negotiating table to iron out an agreement, warning that a strike’s impact on the supply chain “will quickly reverberate throughout the agricultural economy, shutting down operations and potentially lowering farm gate prices.”

Biden does have power to halt the strike. The Taft-Hartley Act gives him authority to seek an injunction against strikes or lockouts that “imperil the national health or safety.” Former president George W. Bush used that authority to reopen 29 West Coast ports after a 2002 lockout.

But one day before the strike, Biden told reporters he has no plans to intervene.

“It’s collective bargaining,” he said. “I don’t believe in Taft-Hartley.”

Editor’s note: Sara Wyant is publisher of Agri-Pulse Communications, Inc., www.Agri-Pulse.com.