The spirit of the Old West lives on in cattle towns

It was 1867 in post-Civil War Texas; the economy was in a major recession following the war and Texas was cattle rich, but poor in marketing opportunities as the railroads had not yet reached the Texas plains. The Longhorn cattle in the state had continued to multiply while the war progressed and by 1860 there were more than six times as many cattle as people in the Lone Star State, according to the Texas Historical Commission. That surplus made cattle worth a measly $2 to $4 a head.

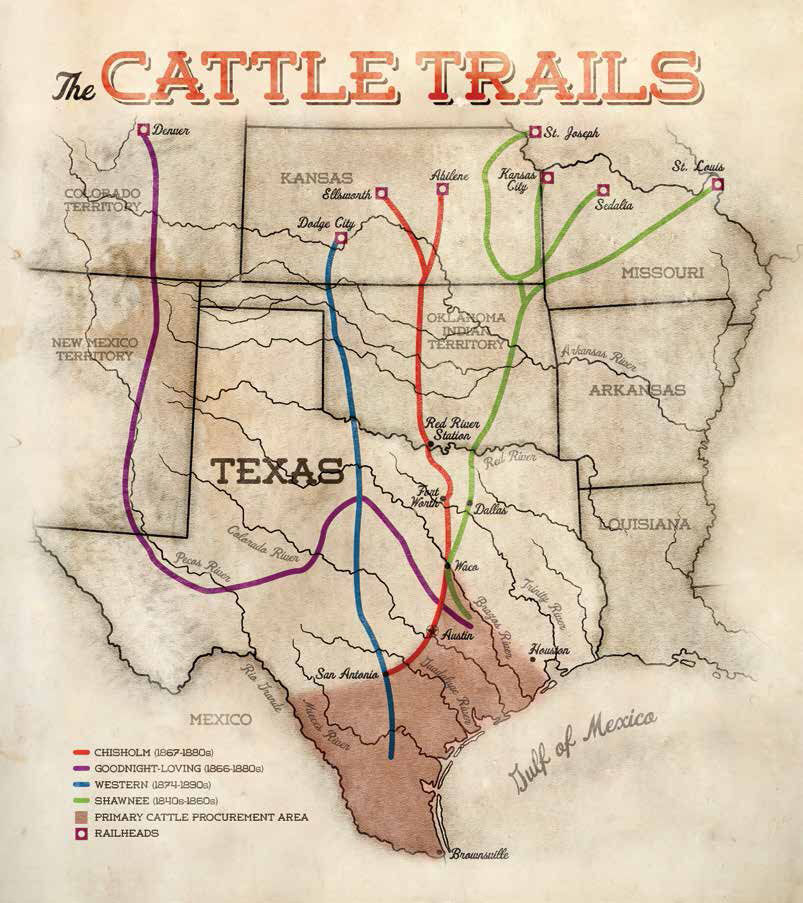

At the same time, markets on the East Coast were experiencing a shortage of beef after most of their cattle were slaughtered to feed soldiers and civilians in the larger cities. To meet beef demands of more populated areas and sell Texas cattle for a healthy profit, cowboys pushed cattle herds of 2,000 to 3,000 head north along several cattle trails, including the legendary Chisholm Trail, which led across Texas, through Oklahoma—then Indian Territory—and on to the towns of Abilene and Ellsworth, Kansas.

“It was during this period that Texas truly became a land of cattle kings and the image of the American cowboy first seeped into national consciousness,” according to the Texas Historical Commission.

The settlements that developed at the intersection of cattle trails and railheads as a result of the cattle drives were known as cattle towns. Their economies thrived off the business brought in by the thundering herds. Once delivered, the cattle were transported by rail to meat packing facilities in Chicago or St. Louis, garnering prices 10 times higher than they would in Texas. As Texas trail driver Bill Butler once said the Chisholm Trail connected the $4 cow with the $40 market.

Although the Kansas Historical Society indicates cattle drives were used as early as 1836, the 20 years of driving cattle from Texas to Kansas and beyond from the 1860s to the 1880s, were the real heyday of cowboy culture. According to the Texas Historical Commission in 1871 alone, about 700,000 cattle reached the railhead in Abilene.

The trails the drovers pushed these cattle along became the original interstate highways of the West, and will forever be correlated with the cowboys that rode them for months on end. Other famous cattle trails include the Western Trail, which began in Texas, trekked across Indian Territory to Dodge City, Kansas, and on to Ogallala, Nebraska. Even though the Chisholm Trail is probably the more famous from its presence in songs and movies, the Western Trail was actually the most utilized by cowboys and according to the Kansas Historical Society, hundreds of thousands of cattle were shipped from Dodge City from 1875-1885. Another popular trail was the Goodnight-Loving Trail, which spanned from central Texas, across New Mexico Territory all the way to Denver, Colorado, and Cheyenne, Wyoming. The Sedalia and Baxter Springs Trail began in Texas, snaked through Oklahoma Territory and forked off to destinations in Baxter Springs, Kansas; Sedalia, Missouri; Kansas City, Missouri; St. Joseph, Missouri and St. Louis, Missouri.

According to the Kansas Historical Society, the cattle drives died out by the mid-1880s mostly due to quarantine laws banning Texas Longhorns carrying diseases like Spanish fever and hoof-and-mouth disease. Additionally, ranchers put up barbed wire fences preventing mass cattle drives across the plains and as the railroad made its way to Texas and refrigeration was invented, the need for driving the cattle across multiple states ended.

To further enforce the historical value of the cattle trails that served as the lifeblood of the West for years, the National Park Service has recently determined that the Chisholm and Great Western cattle trails meet the standards to become National Historic Trails. U.S. Sen. Jerry Moran, R-KS, made the request due to the trails’ importance to Kansas history and its western heritage. Fortunately, labeling these trails as National Historic Trails will not require federal land acquisition and any participation in the program by land owners will be on a voluntary basis. Moran’s office has said this prestigious appointment holds numerous opportunities for tourism, protection of original trail sites and historical education.

Oklahoma City

Although the cattle drives ceased, the cattle industry continued to be the anchor of the towns the drives established. Cities like Fort Worth, Texas; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Des Moines, Iowa; St. Joseph, Missouri; Kansas City, Missouri, and many more developed stockyard facilities for livestock to be bought, sold and slaughtered. While most of the original larger stockyards in cattle towns that operated from the late 1800s to the 1990s are now closed, the Oklahoma National Stockyards, which was founded Oct. 3, 1910, still operates the world’s largest feeder and stocker cattle market with live auctions. Nicknamed “Packingtown” the business closed its packing plant in 1961, but its livestock auction—which is the last terminal market in existence—continues to flourish and has had well over 106 million head of cattle pass through its arch.

Oklahoma National Stockyards President Kelli Payne said the reason she believes Oklahoma City’s stockyards have been able to persevere through the years while other stockyards closed their doors is because it adapted to the times and converted to a live auction, while continuing to allow customers to sell private treaty. Payne believes this decision may have been the difference between the Oklahoma City National Stockyards surviving versus folding.

“With urban sprawl, many stockyards closed and slowly but surely many were replaced with retail, housing or a combination thereof,” Payne said. “The ones left are truly living history, while also providing top markets for farmers and ranchers. They tell a tale of feeding a growing nation well over 100 years ago, and hopefully for the next 100 years.”

Apart from its continued involvement in the cattle industry, the section of Oklahoma’s capital called Stockyards City—where the Oklahoma National Stockyards are located—harnesses the area’s cattle town history and provides an educational and exciting tourist atmosphere. One major draw for Stockyards City is Cattlemen’s Steakhouse, the oldest continually operating restaurant in Oklahoma City, which has been visited by presidents, movie stars, professional athletes and music icons. The area also offers western shopping, dining, nightlife, entertainment and historic buildings and art.

“Much of Stockyards City is on the National Register of Historic Places and retains its original feel and flavor,” Payne said. “Prior to the pandemic, it is estimated that 200,000 tourists graced the Oklahoma City National Stockyards, with close to 500,000 total that visited Stockyards City. Oklahoma City values not only the economic impact that Oklahoma National Stockyards provides, they are also appreciative of the fact we are keeping our western heritage alive. With the close proximity of the stockyards to downtown Oklahoma City and Route 66, it has been a must see for tourists for many, many years.”

Fort Worth

Perhaps one of the most famous cattle towns that has embraced its western culture is Fort Worth, Texas, also known as “Cowtown.” Ethan Cartwright, vice president of marketing at the Stockyards Heritage Development Co., said one of the reasons Fort Worth was so integral in the cattle drives of the late 1800s was that it was the half-way point between south Texas and Abilene, Kansas—an 800-mile journey—so Fort Worth provided opportunities for drovers to restock supplies and was a source of fresh water for cattle.

Although the original stockyard auction held its final sale in 1992, Superior Livestock Auction took the reins and has continued to offer a market place for Fort Worth cattle. According to Cartwright, the Fort Worth Stockyards became a tourist attraction beginning in 1976 with the creation of the North Fort Worth Historical Society. Additionally, in 1989 the Stockyards Museum was opened, and in 1992 local businessman Holt Hickman committed to restoring many of the stockyard’s structures.

The Fort Worth Stockyards National Historic District makes the Old West the focus for tourists with western-themed stores, authentic Texas cuisine and preserved historical structures, like the Livestock Exchange Building and the Cowtown Coliseum—the location of the world’s first indoor rodeo. Additionally, the Fort Worth Stockyards are home to the only twice-daily cattle drive featuring Longhorn cattle and professional drovers. Other popular tourist destinations include: Billy Bob’s Texas—the world’s largest honky-tonk and the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame.

“Fort Worth was once revered as the ‘Wall Street of the West’ for its powerful, livestock-driven economic engine, and today it remains central to the world’s top equine associations, is the broadcast headquarters for RFD-TV and The Cowboy Channel network and a home to many prestigious cattle auctions and livestock trade,” Cartwright said.

Over 3.5 million visitors grace the streets of the Fort Worth Stockyards Historic District each year and it is the No. 1 tourist destination in North Texas with over 850 event days per year.

“History is irreplaceable and Fort Worth chooses to preserve and celebrate its heritage and honor its legacy,” Cartwright said. “The American West was created as the result of cowboys, cattle and agriculture. Fort Worth and the Fort Worth Stockyards served as the gateway to the west and embodiment of the 19th-century manifest destiny.”

Dodge City

Another cattle town steeped in the history of Old West is Dodge City. Synonymous with cowboys like Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, rowdy gunfights and western saloons, this Kansas town is also known for resilience according to Lyne Johnson, assistant director of Boot Hill Museum.

“Ever since its beginning, Dodge City has always had the ability to adapt and reinvent itself,” she said. “It started out as a buffalo hunting area, then it adapted to cattle trails. After the quarantine laws stopped the cattle drives, Dodge City started enforcing prohibition, which drastically changed the way people did business. Then the infamous blizzards came through in 1885 and 1886 and wiped out cowherds. Next, fires burned down the famous Front Street businesses and for most towns in the West, if they had lost that much enterprise, the town would have fizzled out, but in the case of this famous town, the ‘spirit of Dodge’ as residents call it, was able to overcome. I think it still continues to reinvent itself when you look at agriculture today and our ability to stay relevant as a cattle town with Cargill and National Beef facilities being part of the city.”

Boot Hill Museum, opened in 1947, has always been one of the main draws for Dodge City, particularly when the television show Gunsmoke and Marshal Matt Dillon delighted audiences in the 1950s and early 1960s.

“For about the first 30 years that Boot Hill Museum was open, we had Gunsmoke and that really drove people here,” Johnson said. “Most of Gunsmoke wasn’t true and it wasn’t even filmed in the right geographical area, but people wanted to come to Dodge City because of that television show and we still see some of that today.”

Today, Boot Hill Museum welcomes about 75,000 to 80,000 visitors per year. Johnson said visitors from all over the world come to the museum to see the replica Front Street and sit down with a sarsaparilla in hand while taking in the variety show at the Long Branch Saloon. Additionally, Johnson said the museum is in the process of opening a new expansion at the museum, which will include nine new permanent exhibits for the guests to enjoy this summer.

“The Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson and Doc Holliday stories are still out there and very popular today,” Johnson said. “The Wild West is just something that has always been a draw for people, no matter where they’re from. We specifically see a lot of tourists from Europe. They’re just thrilled to come out to the West and see the cattle.”

Even though the years tick farther and farther away from a time when cowboys slept under the stars at night, lullabied to sleep by the low bellows of their herd and straddled trusty Quarter Horses by day with a Colt Peacemaker in their holster, the world never seems to outgrow its fascination with the West or the captivating stories that keep it alive. For the towns that were built by the cattle trails, that legacy is something to cherish, protect and share.

Lacey Newlin can be reached at 620-227-1892 or [email protected].