When temperatures fall, beef producers should watch for signs of fescue foot in their beef herds.

“As the cold weather moves in, you are likely to notice some cows or yearlings on fescue pastures may be slow-moving early in the day,” says University of Missouri Extension livestock specialist Eldon Cole. This might be an early warning sign of fescue foot.

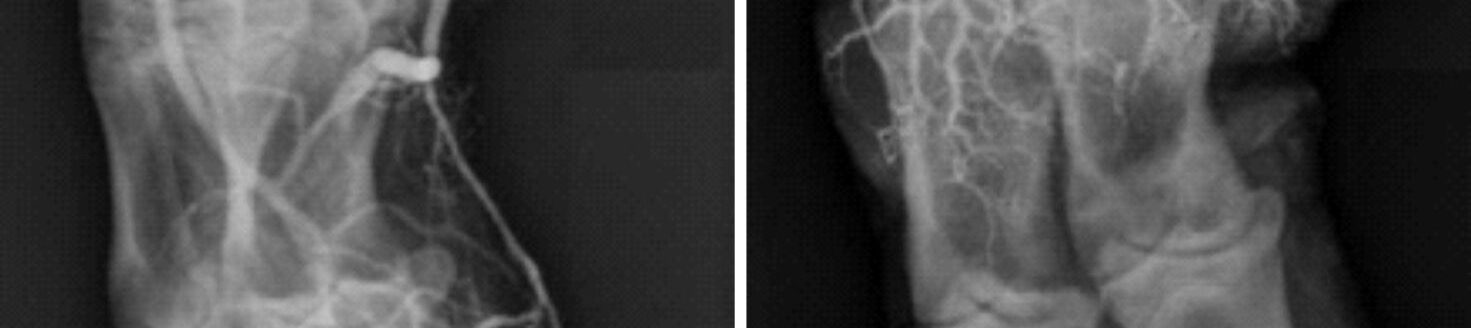

Producers may also notice slight swelling in the rear ankles and possible breaks in the skin from the top of the hoof up above the dew claw, says Cole. Early detection of limping is key. By the time hooves on hind feet show red, gangrene may have set in.

Cole suggests putting the lame animal in a chute and checking its lower leg, which might feel cooler because of the lack of blood flow in that area. “If the animal’s leg feels cooler than the rest of the leg, move the affected animals from that pasture and dry lot them or at least put them on a different pasture,” says Cole.

The toxic alkaloid in fescue is a vasoconstrictor, which shrinks blood vessels. That lowers blood flow to extremities, causing frostbite. Calves lose tips of their ears or switches from their tails. While they may survive, their market value drops. However, cows that develop fescue foot can’t walk or graze.

Fescue foot, first reported more than 75 years ago, is a disabling disease that cripples profits as well.

While there is no cure, producers can replace toxic fescue with a novel-endophyte variety that does not produce the toxic alkaloid. The Alliance for Grassland Renewal offers training on how to renovate pastures. See www.grasslandrenewal.org MU Extension agronomists and livestock specialists also can offer advice on how to prevent fescue foot.