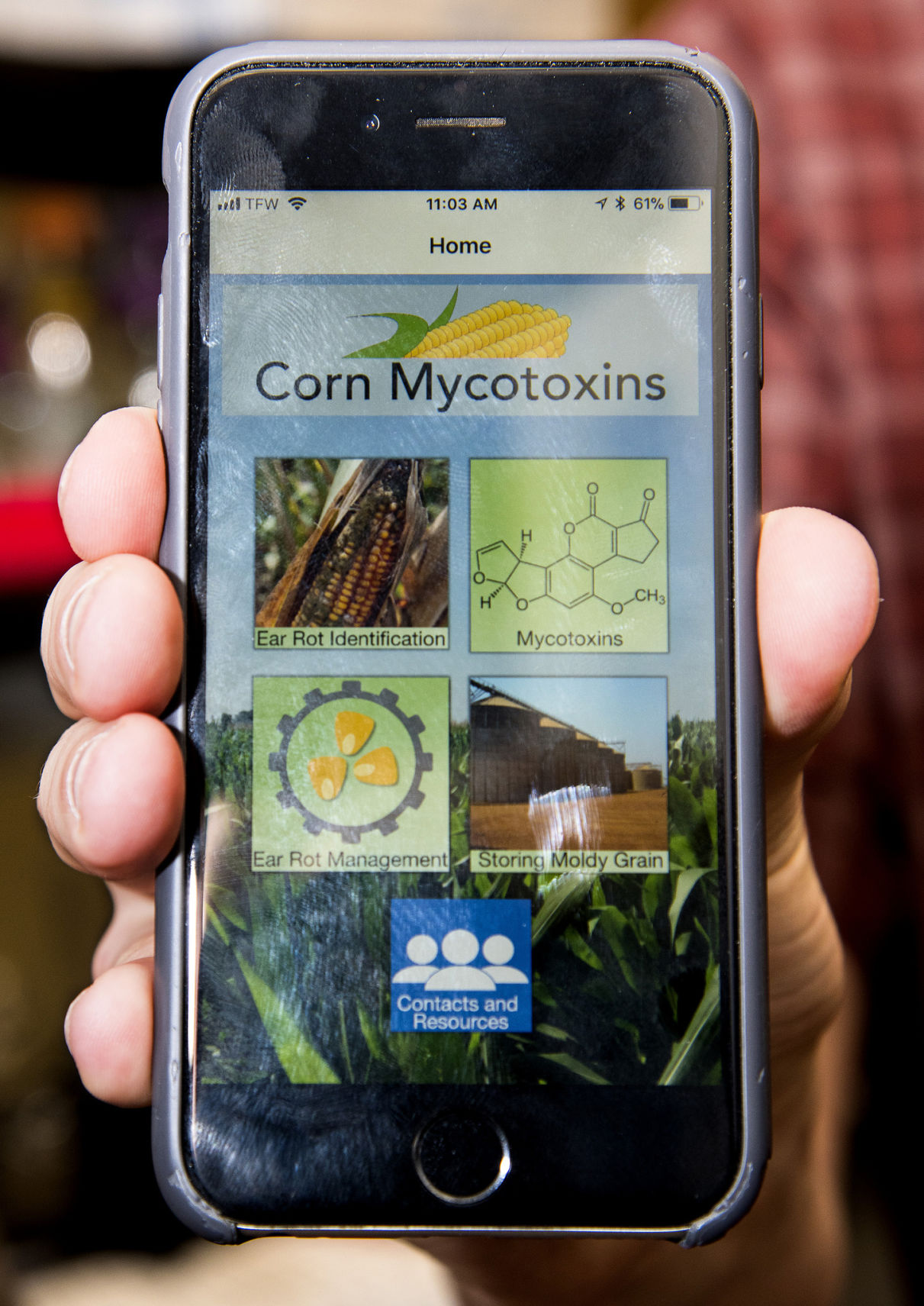

“Mycotoxins,” a mobile app developed by the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture can help corn growers spot dangerous mycotoxin issues and learn what to do about them.

The free, informational mobile app is intended for use by corn growers, crop consultants, county extension agents and others in crop production and seed industries, said Burt Bluhm, associate professor of plant pathology for the Division of Agriculture. It was developed as a collaboration between the division’s department of plant pathology and the department of botany and plant pathology at Purdue University.

Mycotoxins like aflatoxin are dangerous health risks to human and animal consumers, Bluhm said, and they can cause huge economic losses for corn growers.

A 2015 USDA-funded study by researchers at Michigan State University and Iowa State University estimated that aflatoxin, the most problematic mycotoxin disease in the U.S., could cost growers $52 million to $1.68 billion each year.

“Aflatoxin and other mycotoxins can be scary for growers and grain merchandisers,” Bluhm said. “They can pop up at any time and result in big economic losses.”

Mycotoxins are commonly associated with corn ear rot, Blum said. But not all ear rots produce dangerous mycotoxins. The app includes descriptions and high-resolution images that can help growers identify mycotoxins in their corn based on what they see in their fields.

A version of the app for Apple iOS was developed by Alex Zaccaron, a research assistant in Bluhm’s lab. Zaccaron collaborated with developers at other institutions to produce an Android version.

The app is self-contained in the download and doesn’t require an internet connection for use in fields where connections may be poor or non-existent.

Modules in the app include “Ear Rot Identification,” containing descriptions and high-resolution photos to help growers identify the most common corn ear rot diseases. Other modules contain information about mycotoxins, on ear rot management and how to store moldy grain.

A fifth module has contacts and resources where growers and grain merchandisers can find expertise and assistance in their regions.

The app can be used on any Apple or Android smart phone or tablet, Zaccaron said.

Bluhm said the app’s information is based on research he and collaborators have done on mycotoxins. The research is supported across multiple agricultural research institutions by a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture grant. Support in Arkansas also comes from the Arkansas Corn and Grain Sorghum Board, he said.

Among mycotoxins, aflatoxin is considered the most dangerous for humans and animals, Bluhm said. “It’s carcinogenic and primarily associated with liver cancer,” he said.

Other mycotoxins are also considered carcinogenic, Bluhm said. Some of them also can be present in corn, as well as other crops.

“A little aflatoxin goes a long way in corn,” Bluhm said.

Like many mycotoxins, aflatoxin favors hot, dry weather, Bluhm said. This is counter-intuitive for a fungal disease, many of which favor cool, wet weather. “Corn is most susceptible to it when it is stressed by heat and reduced availability of water,” he said.

Generally, Bluhm said, fungicides are not effective in curing or eliminating the disease.

“It’s a weird disease,” Bluhm said. “The fungus gets down in the kernels and fungicides just can’t get at it.”

Bluhm said the U.S. has an effective food safety system that is good at detecting toxins in foods. But the risk may be higher for grains used in animal food or in countries with less stringent food safety procedures.

The biggest risk of dangerous mycotoxins in grains grown for U.S. consumption is economic losses for farmers, who may have to discard an entire crop if infections are extreme, Bluhm said. Livestock producers may also face economic risks.

The “Mycotoxins” app can help growers be confident in the health and safety of their crops and also to help them mitigate the disease.

“They can be confident about knowing what they find in their fields,” Bluhm said.