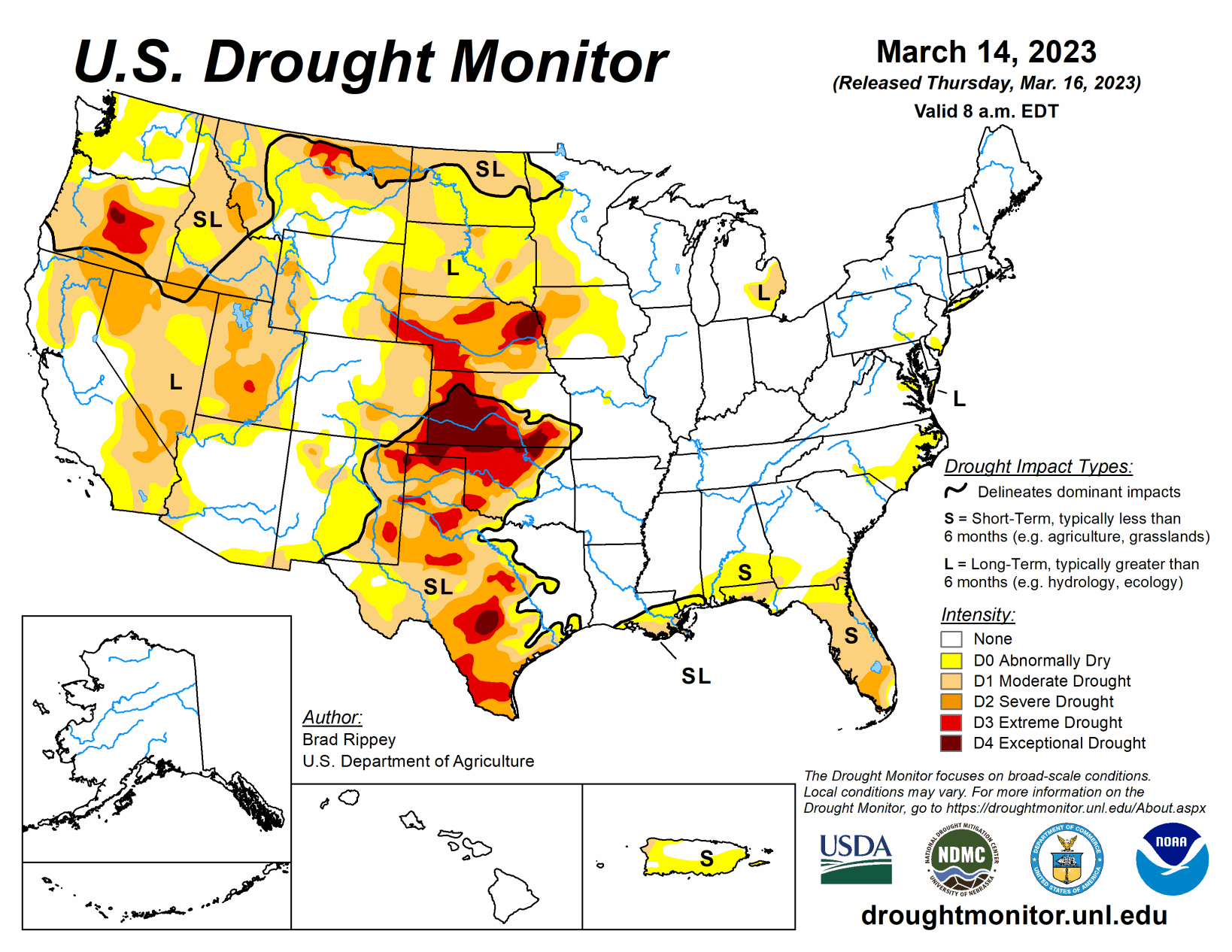

Two atmospheric river events struck California and portions of neighboring states, with the second arriving as the drought-monitoring period ended as reported in the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Torrential rain in central California caused a levee break along the Pajaro River, flooding the community of Pajaro in Monterey County. Rain, along with melting of lower-elevation snowpack and dam releases, also led to significant water rises along many waterways in California’s Central Valley. By March 15, the San Joaquin River at Patterson, California, neared a record crest, with the water rising to within less than a foot of the February 2017 high-water mark.

The average mid-March water equivalency of the high-elevation Sierra Nevada snowpack topped 55 inches, more than 220% normal for an entire season, according to the California Department of Water Resources. Most other areas of the West received mostly light to moderately heavy precipitation.

Farther east, storms delivered light to moderately heavy snow across the northern Plains and upper Midwest, with some of the most significant precipitation falling on March 11. Meanwhile, a band of heavy showers (locally 2 to 4 inches) stretched from northeastern Texas to the southern Appalachians, before shifting into the Deep South. Notably, northern Florida and environs received much-needed rain, following an extended period of record-setting warmth. Farther north, a powerful coastal storm developed as the monitoring period ended, battering parts of the Northeast with heavy, wet snow and high winds.

Mostly dry weather covered the remainder of the country, including the central and southern High Plains, the Rio Grande Valley, and southern Florida. Elsewhere, chilly conditions dominated areas from the Pacific Coast to the northern half of the Plains, while record-setting warmth finally ended cross the Deep South. In fact, freezes were reported for several days, starting on March 14, as far south as Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.

South

The “hot spot” for drought in South remained the southern tier of the region, across northern, central, and western Oklahoma and roughly the western two-thirds of Texas. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 68% of the rangeland and pastures in Texas were rated in very poor to poor condition on March 12, along with 50% of the winter wheat and 47% of the oats.

Additionally, statewide topsoil moisture in Texas was rated 69% very short to short, with values ranging from 92 to 100% very short to short across the Northern and South High Plains, Trans-Pecos, Edwards Plateau, Coastal Bend, and the South region. Meanwhile in Oklahoma, statewide topsoil moisture was categorized as 49% very short to short. Rangeland and pastures in Oklahoma were rated 60% in very poor to poor condition on March 12, while 44% of the state’s winter wheat was rated very poor to poor.

Notably, an extremely sharp gradient existed across eastern sections of Oklahoma and Texas between drought-free conditions to the east and moderate to exceptional drought (D1 to D4) to the west. Elsewhere, moderate drought (D1) expanded across southern Louisiana, where New Orleans, reported just 5.72 inches of rain (51% of normal) for the year to date through March 14.

Midwest

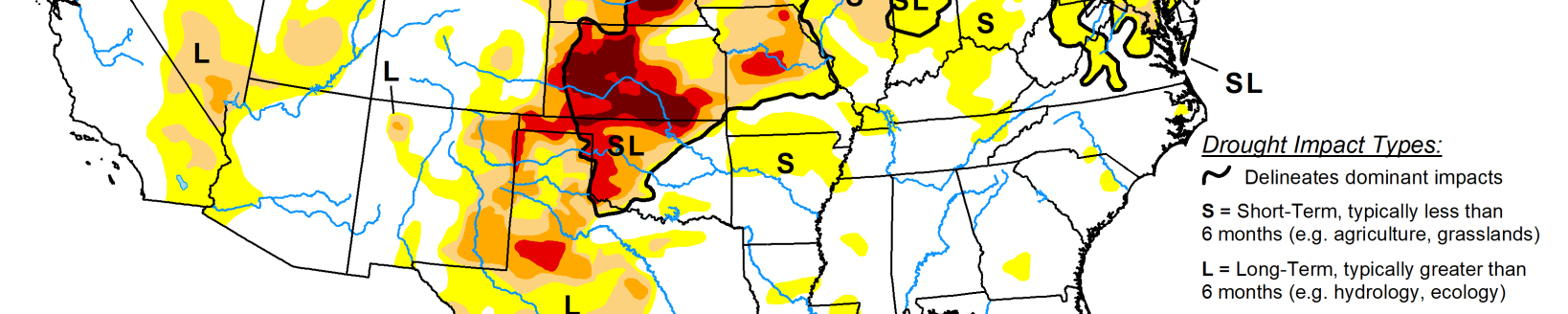

Precipitation during the first half of March further eroded any remaining drought—mainly across southeastern Michigan and parts of Minnesota and Iowa. In Michigan, west of the existing area of moderate drought (D1), Grand Rapids received a daily-record snowfall of 8.7 inches on March 10.

A day later, Des Moines, Iowa, netted a daily-record snowfall of 6.4 inches. In many areas of the far upper Midwest, snow has been on the ground since November. Specifically, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, has had a continuous snow cover since Nov. 29, with the depth peaking at 16 inches in early January. By March 14, the Twin Cities still had 11 inches of snow on the ground.

High Plains

Some of the nation’s most serious drought conditions persisted across southern sections of the High Plains region, mainly across Kansas and Nebraska. Kansas, like other areas of the central and southern Plains, has an impressive gradient between drought-free conditions (in the east) and extreme to exceptional drought, D3 to D4 (in southern and western sections of the state).

On March 12, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, topsoil moisture in Kansas was rated 66% very short to short, while more than half (52%) of the winter wheat was rated in very poor to poor condition. Some of the D4 areas in Kansas received record-low annual precipitation totals during 2022 and have not received much, if any, cold-season drought relief.

In the hardest-hit areas, drought impacts—besides damaged rangeland/pastures and poor winter wheat conditions—include frequent episodes of blowing dust and limited surface water supplies in streams and ponds. Farther north, snow has been on the ground since November in much of North Dakota and portions of neighboring states, with recent cold weather maintaining impressive snow depths even as snow continues to fall. Bismarck, North Dakota, reported at least a trace of snow on 11 of the first 13 days of March, totaling 22.5 inches.

West

Broad reductions in drought coverage and intensity were noted again this week in California and neighboring areas. By March 13, season-to-date snowfall at the Central Sierra Snow Lab at California’s Donner Pass exceeded 650 inches, compared to a normal full-season total around 360 inches.

Meanwhile, Bishop, California (2.06 inches on the 10th), experienced its wettest March day on record, surpassing 1.75 inches on March 4, 1991. Closer to the Pacific Coast, the Pajaro River at Chittenden, California, achieved its highest crest (on March 11) since February 1998.

Looking more broadly at the western U.S., snow-water equivalency values greater than 200% of normal extend from the Sierra Nevada across much of the Great Basin and into parts of Utah. Similarly impressive snowpack values also cover much of Arizona and western New Mexico.

Conversely, snow-water equivalency is closer to normal—and even below normal in some drainage basins—across the northern tier of the West, as well as some areas on the east side of the Continental Divide. Many smaller lakes have rebounded, with California’s 154 primary intrastate reservoirs gaining 9.9 million acre-feet of water between Nov. 30, 2022, and Feb. 28, 2023. California’s storage at the end of February, 23.2 million acre-feet, was 96% of the historical average for this time of year. However, in the Colorado River system, storage on Feb. 28 stood at 15.1 million acre-feet, just 46% of average and 29% of capacity.