Ragweed, its pollen potent to allergy sufferers, might be more than a source of sneezes. In the Midwest, the plant may pose a threat to soybean production.

Scientists have found that ragweed can drastically reduce soybean yield.

“It wasn’t really a weed we were worried about too much,” says Ethann Barnes, a graduate research assistant in agronomy and horticulture at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “We didn’t expect it to be this competitive.”

Weeds compete with crops for light, water and nutrients. Common ragweed, which is taller than soy, has historically been overlooked as a threat. And little is known about its impact on soy in the Midwest.

So, the scientists struck out to a soybean field near Mead, Nebraska. In 2015 and 2016, they planted soybean and ragweed in late spring. Within the experimental plots, ragweed density ranged from no plants (a weed-free control) to 12 plants per meter (about 39 inches) of the row.

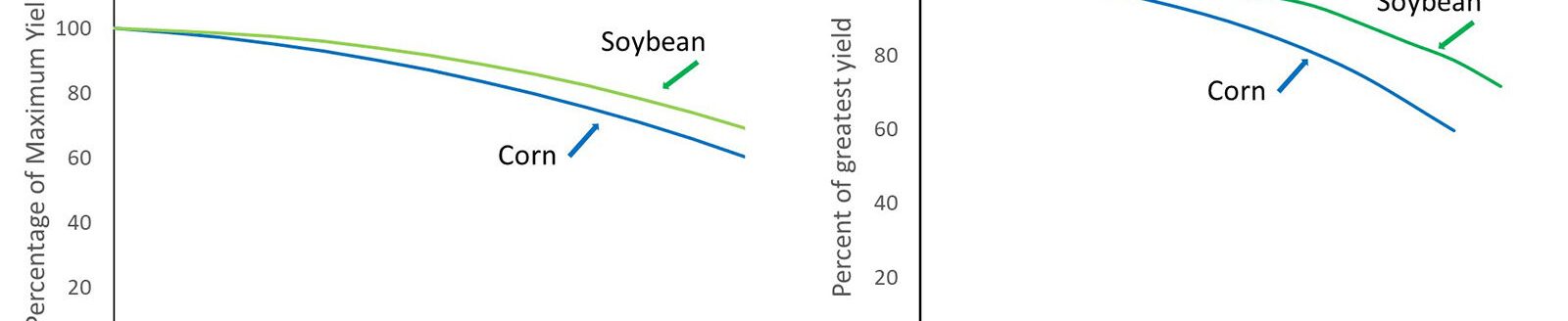

The researchers had two goals: see if ragweed posed a serious threat to soybean and see if there’s a way to estimate the yield loss early in the growing season.

Barnes was surprised by how much the ragweed stifled the soybean in both years. The soybean crops did worse than in previous studies. One ragweed plant every 1.6 feet of soybean row decreased soybean yield by 76 percent in 2015 and by 40 percent in 2016. And soybean yield was reduced by 95 percent in 2015 and 80 percent in 2016 when common ragweed plants were grown only three inches apart in the soybean row.

During the experiment, there was plenty of water to go around for both plants. So, the scientists think ragweed mostly hurt soybean by starving it of sunlight.

“Whether I was presenting at conferences, or even just at my thesis defense, everyone was very surprised how big of a deal common ragweed could be,” says Barnes.

What’s more, it was very hard to predict early in the year how the soybean would fare. Barnes found that not until early August could he plug ragweed numbers into an equation and accurately predict what the soybean loss would be.

Now, Barnes and his team are sharing this information with growers in the area.

“The ultimate goal of this area of science is for growers to count the number of weeds or make a measurement in their field three weeks into the season. From there they could see whether it’s financially a viable option to control their weeds or just leave them in the field,” says Barnes. By knowing how much damage the weeds might do, farmers can weigh that loss against the cost of killing the weeds.

More studies will be needed to hone in on the dynamics of ragweed–and other weed—growth. An end goal, he says, is to predict early in the season how weeds will impede crop yields, so farmers can make better decisions on how to manage them. Such estimates could help farmers know if, when and how much pesticide to apply.

He hopes his study is a step toward that goal. “Hopefully it’ll have an immediate impact for farmers and advance the science of weed competition research.”

The study was published in “Agronomy Journal.” The University of Nebraska Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources funded the project.