How Jon Kinzenbaw beat the competition and built a blue empire

When historians look back at agriculture innovators, a few names come to mind: John Deere and the moldboard plow. Cyrus McCormick and the mechanical reaper. Jethro Tull and the grain drill.

It is fair to say that Jon Kinzenbaw, founder of Kinze Manufacturing in Williamsburg, Iowa, belongs on that list, too.

Kinzenbaw is credited with a host of innovations since his company was founded in 1965. Among the firsts credited to him and his company: the auger-unloading wagon (1965); the adjustable width plow and the two-wheeled grain cart (both in 1971); rearward folding planter (1975); lift and rotate folding planter (1985); autonomous grain cart system (2011); and electric-drive planter meters (2013). And that’s just a partial list.

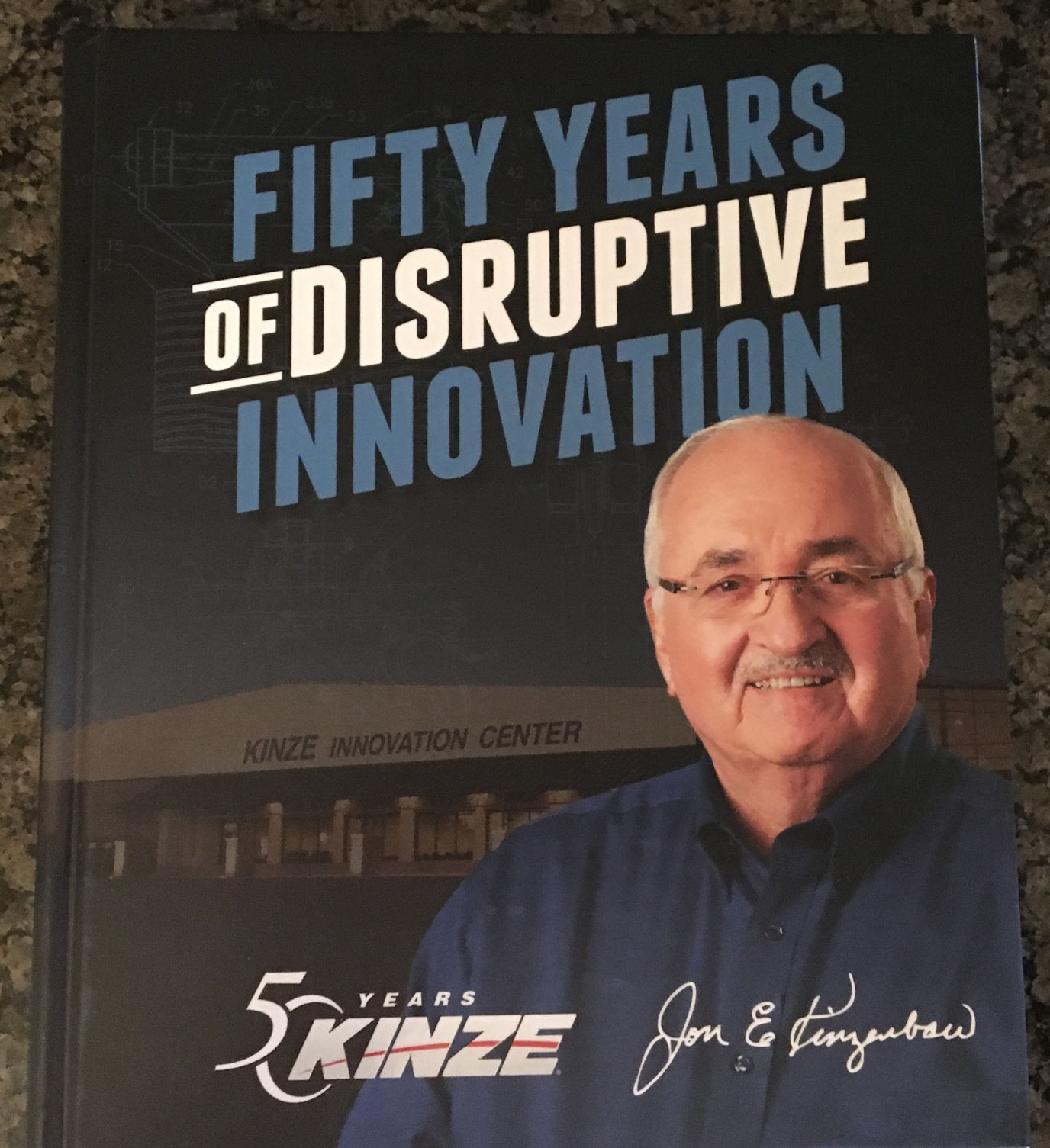

In the twilight of his career, the Iowa inventor has written a book called “Fifty Years of Disruptive Innovation,” which highlights the path he took from a small town blacksmith to creating one of the largest privately held farm equipment manufacturers in the world.

Humble beginnings

Born not far from where the Kinze Manufacturing headquarters is located in central Iowa, Kinzenbaw’s mother was a teacher; his father, a farmer, was a tinkerer. His father, Jack, built their home from a kit bought from the Aladdin Company (buying the kit, he received a complete set of Stanley tools, too). Young Jon was also a tinkerer building his own small-scale models of machines used on the Kinzenbaw farm. In one of the book’s sidebars, he writes of robbing the wheels off a high-quality road grader toy he was given, to make some sort of cart. Although his mother was upset he modified the high dollar toy, that practice of using manufactured components to build new machines is something for which today’s Kinze Manufacturing is well known.

But it wasn’t always that way. The company started out as a welding shop in Ladora, Iowa, in 1965. Before long, Jon Kinzenbaw began building custom projects, including an articulated loader and tractor loaders. He fabricated floater sprayers and fertilizer applicators. He began repowering John Deere tractors. By 1975, the company had outgrown the little welding shop and was doing big business. It soon turned its sights onto the planter market.

Deere hunting

It’s here were the story gets interesting. You may recall the first generation of Kinze planters was essentially a folding bar equipped with John Deere row units. There were 12, 16 and 24 row units, which could easily be transported from field to field. John Deere expressed an interest in partnering with Kinzenbaw to build the folding toolbar with Deere colors, but not at an agreeable payment rate. Before long, Deere cut off the supply of Deere row units, leading Kinzenbaw to file a lawsuit against the company for “antitrust violations and contrived shortages.” In the meantime, Kinze tooled up to build its own row units. Back and forth the two companies went. In summary, let’s just say they won’t be sending each other Christmas cards.

The book is an easy read and contains a lot of Jon Kinzenbaw’s philosophy on business, on dealing with people and details how Kinze Manufacturing will proceed to the next generation (daughter Susie Kinzenbaw Veatch will lead the company). There are details about many of Kinze’s innovations, from tractors, to autonomous grain carts, to tillage tools. Historical photos and sketches add extra insight to Jon Kinzenbaw’s fascinating mind, and page after page of patent applications can be found in the rear of the book.

Now as always, Kinzenbaw keeps farmers first—and whether they use Kinze machines or not, they will thoroughly enjoy learning more about the company’s many innovations, how Kinze took on Deere and won, and have done all this with integrity. On a personal note, I would love to learn more about his leadership style and business philosophy, but that’s not the kind of book this is. It’s a tribute to a legacy of innovation, and a well-done tribute at that.

Bill Spiegel can be reached at 785-587-7796 or [email protected].