Never again does Shelly Elkington want to hear that anyone was one day too late.

Addiction had been far from the mother’s mind when her daughter, Casey Jo Schulte, then in her early 20s, was handed her first opioid prescription to help with the pain of Crohn’s disease. Casey was a college freshman, studying radiology in Fargo, North Dakota, when she was first diagnosed. Eventually, as her pain intensified, her family doctor prescribed her a highly addictive painkiller.

Soon those pills seized the life of a young woman who had been a model student and a state-bound swimmer in the rural Minnesota town of Montevideo, population 5,400. She began running out of the meds early and even used the excuse they were stolen to get more.

“It’s not my fault, Momma,” Elkington recalls her daughter telling her as Casey reached the point of getting help.

“My answer was, ‘It’s not. Of course, it’s not your fault.’”

Casey, however, never made it to her appointment with a pain specialist who was going to help her. One day earlier, on Aug. 19, 2015, in Fargo, Casey was found dead in her garage.

“I wish I had known where to go sooner,” Elkington said, adding the doctor who prescribed the meds later told her, “I didn’t know what else to do.”

A rural epidemic

The battleground is right here in the heartland.

Opioid addiction claims 115 lives each day. In 2016, 42,000 Americans died of an opioid overdose, more than any other drug in the nation, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Farmers and ranchers aren’t immune.

According to an October 2017 survey commissioned by the National Farmers Union and the American Farm Bureau Federation, three of four farmers and farm workers—about 75 percent of the population—either have taken an illegal dose of painkillers, know a family member or friend who is addicted or are dealing with addiction themselves.

Those stats are evident from the patients coming through the doors at Valley Hope, a non-profit drug and alcohol treatment organization with 16 facilities across seven states.

“Most of the people here have some sort of experience growing up on a farm or a job directly related to agriculture,” said Javier Ley, a licensed clinical addiction counselor for the Norton, Kansas-based organization.

Patients with opioid addiction have more than doubled in the past decade, reaching 30 percent of the center’s caseload. Opioids now rank No. 2 behind alcohol, surpassing methamphetamines, said Pat George, a former lawmaker and Kansas Commerce secretary who has served as Valley Hope’s chief executive officer since 2015.

Many of the patients are younger. In the 18-to-25 age range, patients with opioid addiction dramatically increased from almost 30 percent to more than 51 percent since 2007.

Those inflicted might be the small-town athlete who goes in for knee surgery, he said. Or it is a farmer who might have been working cattle and was kicked.

“Whatever the reason, I might have back pain or pain in my knee and the doctors give me a pill to deal with the pain and it helps,” said George. “We deal with a lot of farmers, and we think there are a lot more out there who have developed an addiction. We want to try to reach those people.”

How did it start?

An obstetrician-gynecologist in the Barton County seat town of Great Bend, population 15,000, Dr. Roger Marshall watched the epidemic emerge into a serious problem in some Kansas counties. Now finishing his first term in Washington, the Big First Kansas Republican congressman is tackling the issue.

In August 2017, he joined in on a bill called the Addiction Recovery for Rural Communities Act, which would help rural communities bolster their efforts to fight the growing opioid and addiction epidemic.

Marshall said part of the program was to provide funding for telemedicine and new treatment centers, plus funding for education and outreach. About $6 million was appropriated in the March spending bill and Marshall said he sat down with Jerome Adams, the U.S. surgeon general, to talk about a public service campaign.

Marshall said it’s time to start doing something.

“We can’t underestimate the problem. It’s time to stop praying and forming committees and talking about it,” he said. “Let’s figure out what is causing the problem and start working on solutions.”

That includes educating doctors about dependence.

“How much narcotics should we be prescribing?” the congressman said.

Marshall said the epidemic began to grow in the late 1990s with health care providers feeling pressure to better treat patient pain.

Pain, he said, was considered a fifth vital sign.

Medicare, Medicaid and other insurance providers rated that ability with reimbursement hinging on those ratings, Marshall said.

For instance, patients might take an opioid like hydrocodone or oxycodone following surgery, a toothache or something else.

Soon, Marshall said, patients sent home with 10 days of drugs might have them used up in three or four days, “Because they were told they shouldn’t have pain. It backfired and more and more people ended up addicted.”

Moreover, said Valley Hope’s George, no one talked about the side effects for a long time.

“We were creating these addicts, so to speak.”

An emotional crutch

Casey’s painkillers were for digestive pain, Elkington said. But it also made her other problems feel better, too.

“They also impact your brain. You like them. You need them and when you are young and hurting and not doing what your classmates are doing, you develop some emotional issues and the pain pills help with that.”

Casey grew up in the small town where her family was already deeply rooted. Elkington’s husband repaired electric motors for farmers and her mother owned a small business. Her dad was a teacher and Elkington and her father both helped operate the local ambulance.

And Casey—a brown-eyed girl who dreamt of going into the medical field—possessed that same desire to help others.

She completed her first year at North Dakota State University, but with the pain, returned home where she worked at the local hospital as a phlebotomist before resuming school in Alexandria, Minnesota, for nursing.

“People who worked with her loved her,” Elkington said.

But the agony continued. She began seeing a gastrointestinal doctor and her regular physician, who prescribed opioids.

Her intestine narrowed to the size of a pencil. Casey’s weight dwindled to 87 pounds.

“She was horrifically malnourished and taking these pain medicines,” Elkington said. “It was this perfect storm.”

Casey was admitted to the hospital to remove part of her colon. Her recovery was horrific, Elkington said. Her daughter begged for more pain medication, but the hospital staff didn’t want to give her too many, fearing she might stop breathing.

“She had already been on the pain medications so long she didn’t get pain relief. That was the first time I noticed we were in deep trouble.”

A few weeks later, she was admitted again. Her abdomen was swollen and infected. She was septic.

Elkington recalled riding in the elevator with the anesthesiologist, who told her he had to give Casey enough anesthesia to treat a 300-pound man.

“It started with pain and it ended up being an emotional crutch,” Elkington said.

Street opioids

Patients with addiction often have other trauma in their life, George said.

He is one of them. Now a 26-year recovering addict, George said he grew up in a dysfunctional home and turned to alcohol and drugs, which took away the emotional pain.

That’s the same for opioid abusers, he said. As was the case with Casey, often those addicted have other medical conditions. Or, they could have depression, anxiety or prior problems with drugs or alcohol.

If doctors eventually cut off the supply, addicts might search for other ways to feel good. Some move to heroin, which is cheap and accessible, George said. Even in rural areas like Norton, he said, they can find the drug within an hour of needing it.

“It’s readily available, unfortunately,” he said.

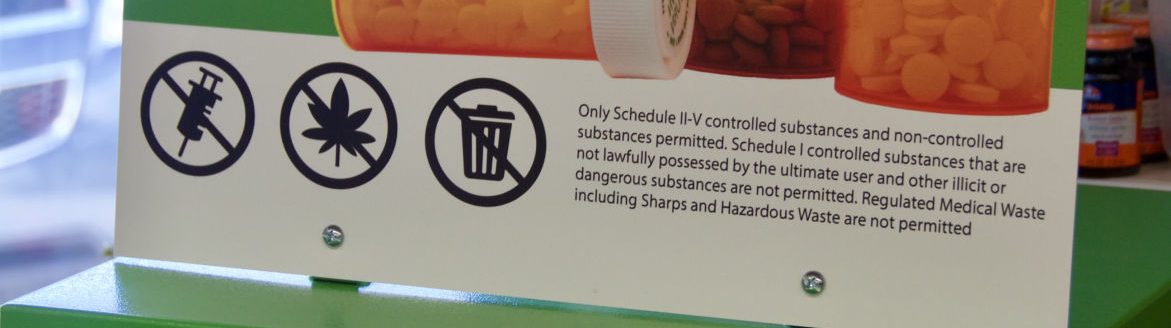

Street opioids are now a bigger problem than prescription opioids. In recent years, overdose deaths are overwhelmingly attributable to illicit fentanyl and heroin.

A research letter published in the May 1 edition of “Journal of the American Medical Association” concluded that nearly half of opioid-related deaths in 2016 involved fentanyl.

The report also noted that of the 42,000 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2016, about 46 percent involved fentanyl and 40 percent were from prescription opioids. Another 36 percent involved heroin.

Advocating for Casey

Elkington said she tells Casey’s story because if one person can be touched by it, her loss stings a little less.

She talked to her daughter the day before she died, putting money into her account so she could get from Fargo to the center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

It’s not clear what happened on Aug. 19, 2015. Casey’s new friends were a questionable crowd, her mother said.

Autopsies showed she died from hanging.

“We have a lot of thoughts about Casey’s last day,” she said. “Regardless of the nature, she was in a lot of agony—mentally, physically and emotionally.”

But it still haunts Elkington. She was one day too late.

“That doesn’t escape me—I don’t want anyone to be one day too late.

“This is forever,” she added. “I don’t have any more chances.”

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].