Call it saving for a dry spell.

The idea was to have water available down the road for Wichita’s growing population.

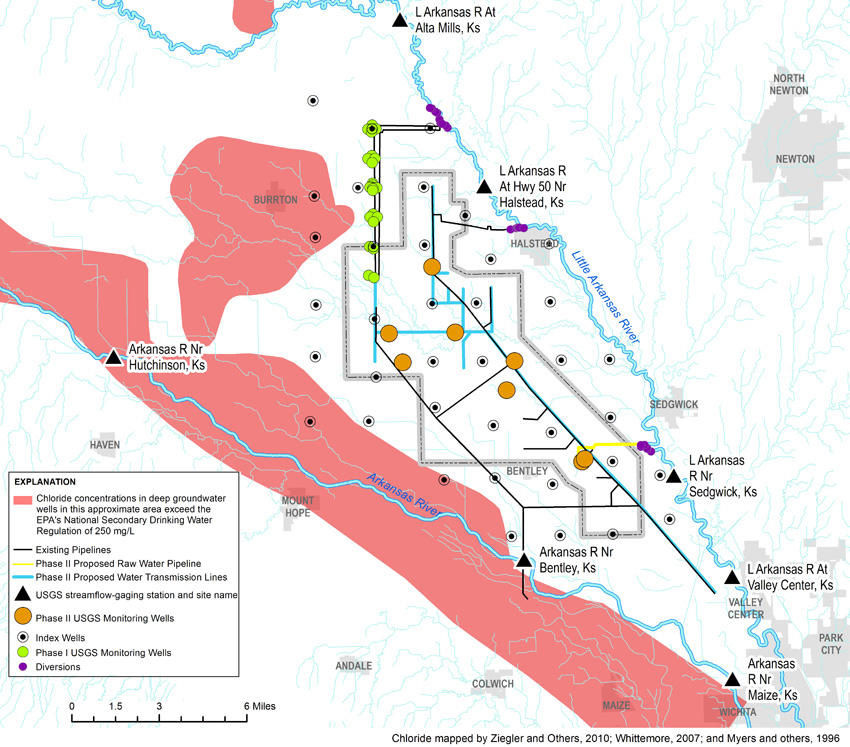

In theory, it’s an engineering marvel—injecting surplus water from the Little Arkansas River into the ground like a gigantic bank deposit to be withdrawn when needed in the future. And while aquifer storage and recovery isn’t anything new in other parts of the world, in Kansas, it is the first—and only—of its kind.

But such a concept has created a 20-year urban vs. rural battleground in the fields of south central Kansas. The project’s beginnings in the mid-1990s were marked with heated debates and lengthy meetings between farmers, landowners and Wichita officials. And, now, a new proposal to the state by Wichita on how it operates the project, it seems, has revived some of the past contention, which was evident at a public informational meeting June 28 in Halstead.

“Why aren’t we using an outside source rather than you,” one resident in the audience asked Division of Water Resource Chief Engineer David Barfield, questioning whether Barfield already had his mind made up, favoring Wichita.

The issue centers around Wichita’s present quandary. The aquifer in the city’s wellfield area is nearly full, reaching 98 percent capacity in 2017, said Joe Pajor, deputy director of public works and utilities for Wichita, who also serves on the Equus Beds Groundwater Management District board.

Now Wichita wants credit for the water it can’t recharge with plans to dip into those credits during a 100-year drought.

“Right now, if they take it directly to town, they don’t get any recharge credits for it. And that is the fundamental change they want,” said Equus Beds Manager Tim Boese. “When the aquifer is fuller or full, they could take the water, treat it and take it to town and get credit for it like they have put it in the ground. That is a huge fundamental change.”

Background

In the early 1990s, during a period of drought, Wichita officials knew they needed to do something to sustain their long-term water supply for residents. Wichita has water rights in both Cheney Reservoir and the Equus Beds. By 1992, however, the city, along with irrigators and other water users, had drawn down the aquifer to a record low level, reducing it more than 200,000 acre-feet near Wichita’s wellfield.

City officials explored several ideas for future water needs, including one to pipe water from Milford Lake. Yet, along the Little Arkansas River in Harvey County, they came up with the revolutionary concept.

They would pump it back into the earth and, in the meantime, switch the city’s primary water use to a right in Cheney Reservoir in an effort to build back the Equus reserve.

Pajor said officials never expected the aquifer to refill so fast. Recovery is primarily due to the city using more water from Cheney Reservoir and less groundwater from the Equus Beds since the mid-1990s. Better irrigation practices and rainfall also has helped.

Double dipping?

During the 2011-12 drought, water levels dropped in both Cheney and the Wichita well field. Officials grew concerned that ASR permit limits for the minimum index level might prevent the city from accessing recharge credits during drought periods when water is most needed.

The city has been working with DWR to address concerns regarding the ASR restrictions.

The plan is based on what would happen if Wichita were to experience a drought like the Dust Bowl days of the 1930s. That is considered a 1 percent drought, happening every 100 years.

The current plan would allow the city to handle such a drought through 2060.

Besides changing the method to accumulate recharge credits, the city is asking DWR to lower the limit of when credits can be used, plus approve a series of new applications to allow the city to recover recharge credits at its existing production wells.

Recharge credits would be capped at 120,000-acre feet, Barfield said. Equus Beds officials are questioning whether that number is appropriate, since the city needs less than 60,000-acre feet of recharge credits during a 1 percent drought, Boese said.

“We’re still evaluating in our office whether it is legal,” Boese said of all the proposals. “The chief engineer seems to think it is.”

Meanwhile, with no room to inject water, city officials have two options under current regulations. They could draw down the Equus Beds so they could make storage space available for Little Ark injections, thus earning recharge credits that count toward future water use. Or, they could treat the water they can’t inject and use it without recharge credits.

Wichita shifted its main water use from Cheney to the Equus Beds this spring in preparation that their proposal to DWR is rejected, which created more concerns from the Equus Beds board, Boese said. He sent a letter on behalf of the board to the city of Wichita in April stressing the city’s change in tactics would threaten their long-term stewardship of the resource.

Landowners are also concerned about the impact on irrigation during a drought, Boese said.

“You are giving someone a recharge credit for not physically putting water into the aquifer,” he said. “That is a new, foreign concept.”

One water user in the crowd compared the city’s proposal to negative withdrawals from a bank account.

“So, if I go to the bank and I have a $100,000 deposit, and I pull out $90,000 and I go back and tell them I want to go back and pull out another $100,000 because I didn’t take it out before, they are going to be happy with that?”

Barfield told him he didn’t think that equated but suggested he provide written testimony for a public hearing scheduled for August.

Dennis Gruenbacher, a farmer near Andale, expressed concern the city might use the water to sell to other communities that are not part of its current customer base.

Pajor said that wasn’t the case. Wichita has 11 other customers representing 77,000 people around Wichita.

“There is a significant regional role this water plays,” he said.

Upcoming public hearing

Jeff Winter, a farmer near Andale who is also the Equus Beds board president, said the concern is what will happen to the local water under the new regulations.

Another issue is the underlying reason for the ASR project has changed.

“When the ASR was developed, was this what it was developed for or not?” Winter asked. “There are continued issues and questions about this.”

Barfield said the agency’s goal is how, within the law, Wichita can accomplish their needs with ASR.

“They have come up with a way to do this that is really, in our view, in everybody’s best interest,” Barfield said. “It allows the city to accomplish this objective while maintaining a full aquifer.”

Barfield said he planned to have a public hearing in August and make a final decision this fall.

Amy Bickel can be reached at 620-860-9433 or [email protected].