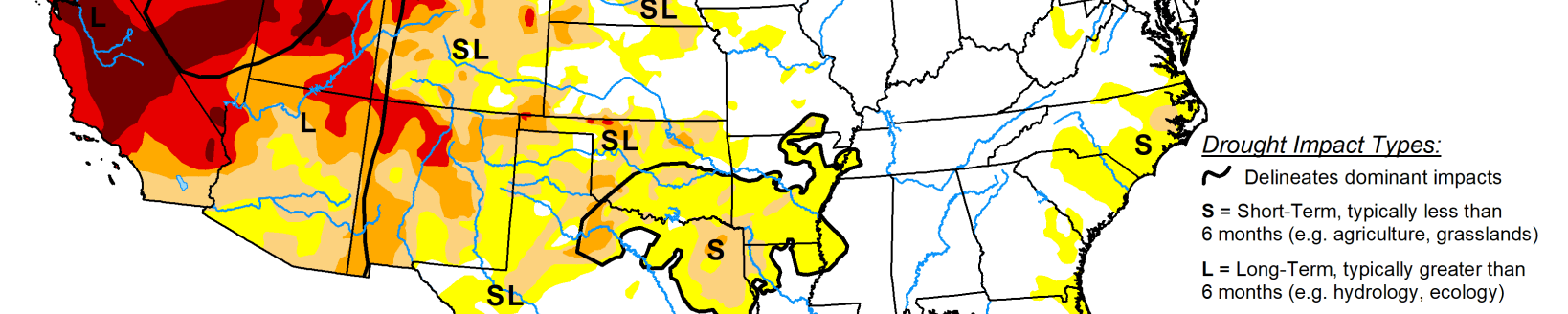

Recent multi-year droughts accelerated groundwater-level declines in the High Plains aquifer as pumping increased to compensate for lack of rain. Those loses underscore the dilemma western Kansans could face if water levels fall too low to support irrigation and other water needs in hard-hit regions of the aquifer.

“If water use becomes unsustainable, farmers will eventually have to convert to dryland farming,” said Don Whittemore, Kansas Geological Survey Senior Scientific Fellow Emeritus.

Besides affecting irrigation, continued groundwater declines could threaten municipal and industrial water supplies. Lower water levels have already impacted rivers and creeks interconnected with the aquifer in western Kansas, which can damage near-stream wildlife habitat.

As part of an effort to monitor and maintain the health of the High Plains aquifer, the Kansas Geological Survey at the University of Kansas has released a new publication, “Status of the High Plains Aquifer in Kansas,” that provides an assessment of the aquifer’s condition and highlights areas most at risk. It also advances an innovative water-balance approach developed at the KGS for estimating how far pumping would have to be cut back to extend the life of endangered sections of the aquifer.

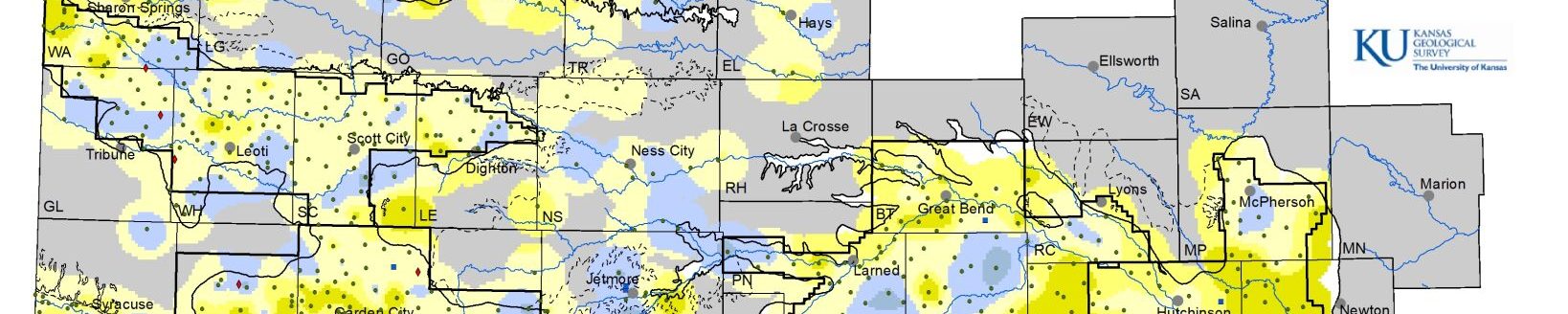

Underlying portions of eight states from South Dakota to Texas, the massive High Plains aquifer stretches irregularly across western and south-central Kansas, reaching as far east as Wichita. It includes the extensive Ogallala aquifer, in decline for decades in much of western Kansas, and the less-challenged Great Bend Prairie aquifer and Equus Beds in south-central Kansas.

“Years of monitoring water use and water levels in the Kansas portion of the High Plains aquifer has provided us with the high-quality data necessary for estimating the pumping reductions needed to sustain water levels,” said Whittemore, who is lead author of the publication.

Data and analyses in the new publication are provided for each of the state’s five Groundwater Management Districts, which fall within the High Plains aquifer boundaries and are organized and governed by area landowners and local water users to address water-resource issues.

The KGS amasses water-level data from about 1,400 wells measured annually by the KGS and the Kansas Department of Agriculture’s Division of Water Resources. Water usage for each well with a water right is reported to the Kansas Department of Agriculture by the water-right holders.

“The data we collect allow us to define the water-resource conditions and issues and to evaluate progress toward achieving goals laid out in the state’s Long-Term Vision for the Future of Water Supply in Kansas report,” Whittemore said.

The state’s water vision plan, released in 2015, was drawn up to ensure a continuing reliable water supply in the state. It provides a framework for protecting and managing the state’s water resources—aquifers, streams, and lakes—in collaboration with water stakeholders.

The KGS water-balance approach advanced in “Status of the High Plains Aquifer in Kansas” is being used to estimate how much pumping has to be diminished in different parts of the High Plains aquifer to achieve a zero water-level change. Calculations made with this method show that reductions may not have to be as drastic as originally thought.

The results indicate groundwater levels could be sustained in most of the imperiled areas of western Kansas for at least one to two decades by reducing pumping between about 27 percent and 33 percent. That’s higher than the 20 percent reductions economic analyses indicate can be made without substantially affecting farming operations but significantly lower than those forecast using standard numerical models.

Numerical models calculate water-level changes based on the individual effect of each inflow and outflow component to the aquifer, including precipitation recharge, stream-aquifer interaction, transpiration through plants, and pumping.

“Accurate quantification of these individual components is, in principle, relatively straightforward, but rarely, if ever, achievable in practice because we don’t have enough data,” said Jim Butler, KGS geohydrology section chief and coauthor of the report. “The strategy of the KGS water-balance method is to lump all aquifer inflows and all aquifer outflows except pumping under a single term, net inflow.”

Consequently, the KGS method is dependent on just two components—annual water-level data, and the amount of water pumped, which is reported by water users.

"This new approach exploits the great water data we have in Kansas,” Butler said. “With it, we are able to develop reliable evaluations of what the future holds for our state’s most important aquifer over the next one to two decades.”

“Status of the High Plains Aquifer in Kansas” is available online at http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Bulletins/TS22/index.html or in print from the Kansas Geological Survey on KU’s West Campus, at the KGS Wichita Well Sample Library, or through http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/pubIndex.html.